index●comunicación | nº 14(2) 2024 | Páginas 321-345

E-ISSN: 2174-1859 | ISSN: 2444-3239 | Depósito Legal: M-19965-2015

Recibido el 17_01_2024 | Aceptado el 30_04_2024 | Publicado el 01_07_2024

#IAMNOTAVIRUS -TRANSNATIONAL ACTIVISM OF CHINESE DIASPORA DURING COVID-19

#NOSOYUNVIRUS - ACTIVISMO TRANSNACIONAL DE LA DIÁSPORA CHINA EN LA COVID-19

https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/14/02Iamnot

Denise Cogo

Escola Superior de Propaganda e Marketing

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4544-7335

Luiz Peres-Neto

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

luiz.peres@uab.cat

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8190-8720

Amparo Huertas Bailén

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

amparo.huertas@uab.cat

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8851-5417

This study has been supported by National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) – Brazil

![]() To quote this work: Cogo, D., Peres-Neto, L and

Huertas-Bailén, A. (2024). #IAmNotAVirus. Transnational

activism of Chinese diaspora during Covid-19. index.comunicación, 14(2), 321-345.

https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/14/02Iamnot

To quote this work: Cogo, D., Peres-Neto, L and

Huertas-Bailén, A. (2024). #IAmNotAVirus. Transnational

activism of Chinese diaspora during Covid-19. index.comunicación, 14(2), 321-345.

https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/14/02Iamnot

Abstract: This article analyzes the digital transnational activism of the Chinese diaspora that aimed to confront racist and xenophobic narratives on the expression «Chinese virus» during Covid-19. We focus on the process of creation and production of two campaigns in Brazil and in Spain, #EuNãoSouUmVirus and #YoNoSoUnVirus, respectively, shared on YouTube and X (former Twitter). Based on a qualitative approach, we combine ethnographic observations and in-depth interviews with three activists. The analysis is developed around two dimensions that marked the campaign in the two countries: (1) the emergence of racist and xenophobic narratives around the «Chinese virus» as an impulse towards transnational digital activism and (2) the activism of the #EuNãoSouUmVirus/#YoNoSoyUnVirus campaign as an opportunity for political engagement in the context of Chinese culture. While social media campaigns often align with short-term loyalties in consumption, results indicate that it can also be an opportunity for participants to reflect on their diaspora process and fight for political recognition at a local and transnational level.

Keywords: Chinese diaspora; Digital activism; Social media; Transnationalism; Political engagement; Covid-19.

Resumen: Este artículo analiza el activismo digital transnacional de la diáspora china cuyo objetivo fue enfrentarse a las narrativas xenófobas basadas en la expresión «virus chino» surgida con la Covid-19. Nos centramos en el proceso de creación y producción de dos campañas, en Brasil y España, #Eu NãoSouUmVirus y #YoNoSoyUnVirus, respectivamente, desarrolladas en YouTube y X (antes Twitter). A partir de un enfoque cualitativo, combinamos observaciones etnográficas y entrevistas en profundidad a tres activistas. El análisis aborda dos dimensiones que marcaron las campañas en ambos países: (1) el surgimiento de narrativas racistas y xenófobas en torno al «virus chino» como estímulo del activismo digital transnacional y (2) el activismo de la campaña #EuNãoSouUVirus/#YoNoSoyUnVirus como una oportunidad para reforzar el compromiso político en torno a la cultura china. Aunque las campañas en las redes a menudo coinciden con acciones a corto plazo, los resultados indican que también pueden ser una oportunidad para que los participantes se planteen su condición como miembros de una diáspora y luchen por el reconocimiento político a nivel local y transnacional.

Palabras clave: diáspora china; activismo digital; redes sociales; trasnacionalismo; compromiso político; Covid-19.

1. Introduction

In late 2019, early 2020, when the first cases of Coronavirus were located in the city of Wuhan, China, the expression «Chinese virus» became popular and instigated, in different countries around the world, racist and xenophobic actions against Chinese people and other Asian nationalities. In order to avoid terms such as «Chinese virus» or «Brazilian variant», the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations (UN) promoted actions that would allow discouraging the use of xenophobic or racist expressions and evidencing that the main problem to be faced was a matter of global public health, not limited to certain nations or locations. Thus, both organizations began to defend the use of the term Covid-19 and the letters of the Greek alphabet to designate the variants of this new virus.

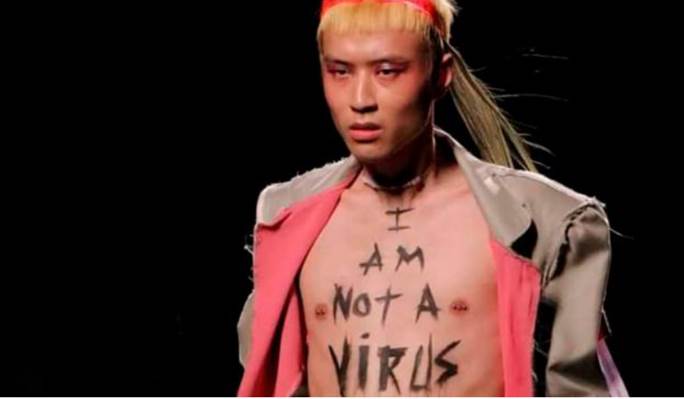

Within this context, we observed, on February 2020, a new transnational and decentralized movement on social media, shared initially on X (formerly known as Twitter), with the hashtags #IamNotaVirus, #JeNeSuisPasUnVirus, #YoNoSoyUnVirus and #EuNãoSouUmVirus. The movement gained momentum after a Spanish multi-artist and performer of Taiwanese descent Chenta Tsai Tseng (@putochinomaricon), known for his activism against racism and in favor of the LGBTQIA+ community, walked on Madrid Fashion Week with the campaign slogan painted in his torso. In addition, we’ve verified a dissemination of the campaign on other digital platforms such as YouTube, Instagram and Facebook, as well as on mainstream websites and media platforms (Ahijado, 2020).

Image 1. Performance of the multi-artist Chenta Tsai Tseng on Madrid Fashion Week

Source: Reasonwhy.es (2020).

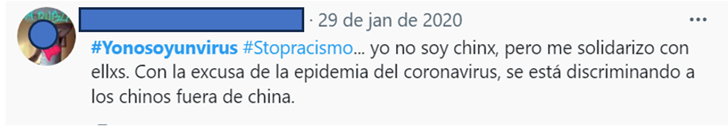

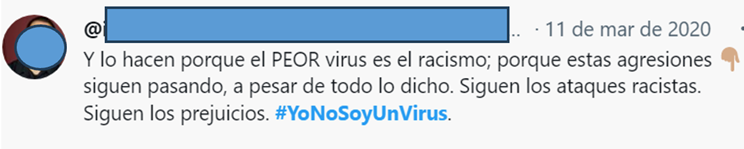

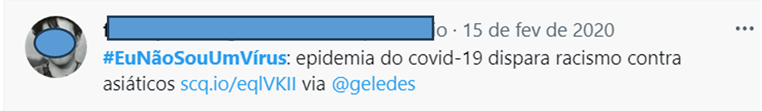

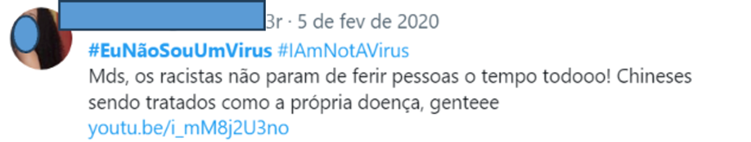

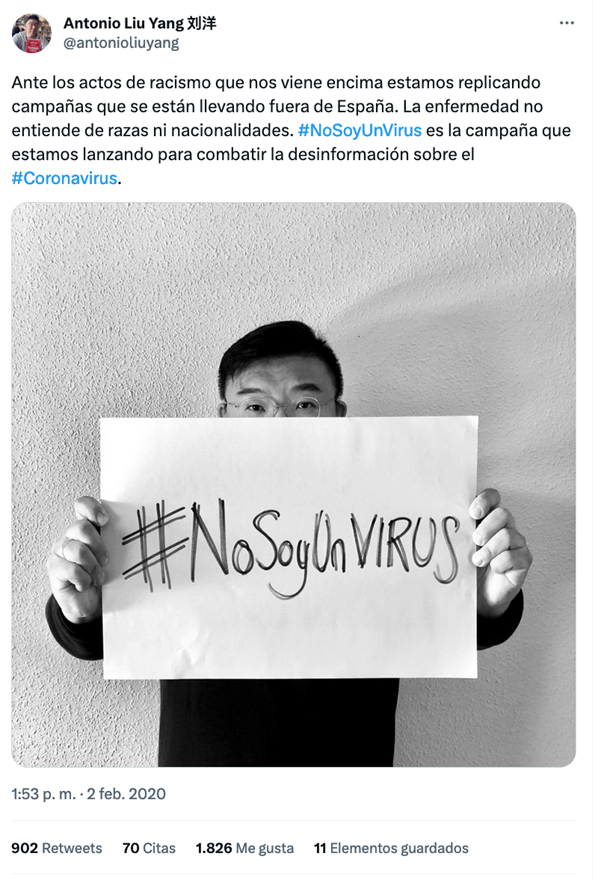

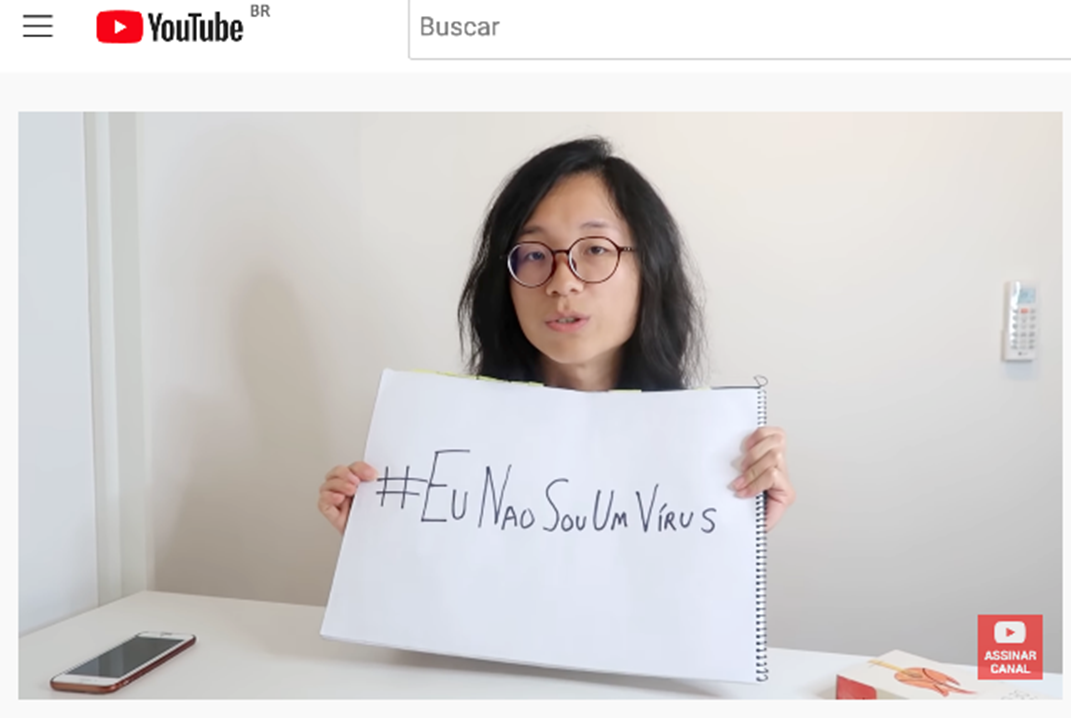

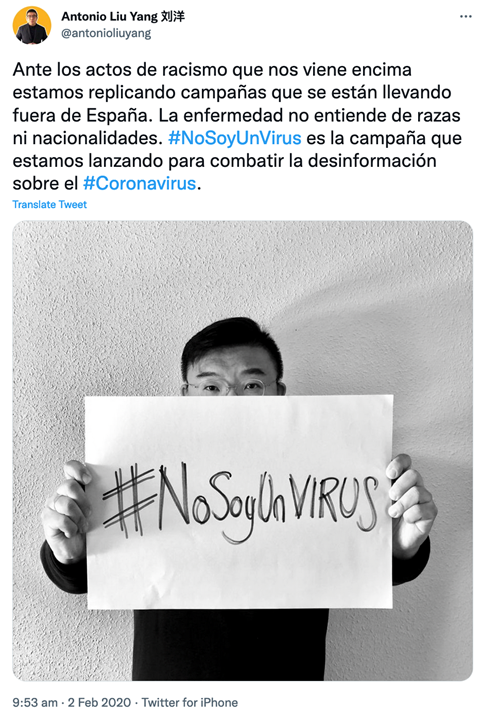

These first observations, the first step for outlining this research, indicated that this was an activism that, with a short and direct message, sought viral and quick recognition on social media through the hashtag «I am not a virus», which allowed Internet users to commit to an anti-racist and axenophobic ethos, with the example of social media activism campaigns such as #JeSuisCharlie or #BlackLivesMatter, among others, which had an extensive affiliation and repercussion (Ciszek, 2016; Gerbaudo & Treré, 2015). The following comments (Images 2, 3, 4 and 5) exemplify this type of commitment observed through posts of common users, in other words, people without necessarily a wide number of followers.

Image 2. Post published on X (former Twitter) with the hashtag #YoNoSoyUnVirus

Source: X (Twitter.com).

Image 3. Post published on X (former Twitter) with the hashtag #YoNoSoyUnVirus

Source: X (Twitter.com).

Image 4. Post published on X (former Twitter) with the hashtag #EuNaoSouUmVirus

Source: X (Twitter.com).

Image 5. Post published on Twitter with the hashtag #EuNaoSouUmVirus

Source: X (Twitter.com).

With the use of 4CAT (Peeters & Hagen, 2022), we monitored social media posts published between January 15th and March 15th, 2020. On Table 1, we exposed the total of post identified by language with the hashtag #EuNãoSouUmVírus in Portuguese and its variants in English, Spanish and French. These were the four languages with the biggest incidence of posts within the period we monitored.

Table 1. Total of posts

|

|

English |

Spanish |

Portuguese |

French |

|

Tweets |

1075 |

>17,700 |

>18,300 |

>39,800 |

Source: Own creation through data collected on X (former Twitter).

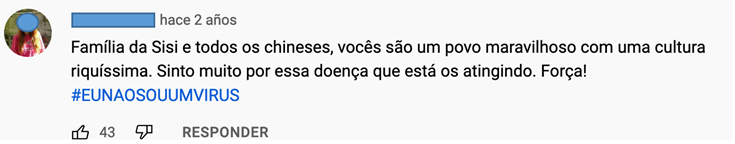

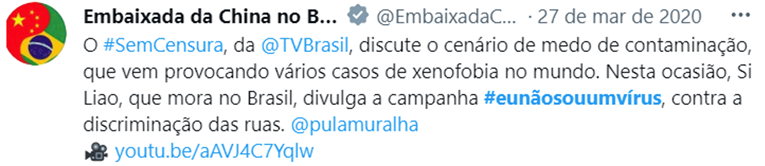

The initial observation identified a significant volume of posts in Portuguese, Spanish and French. Even though the monitoring tool wouldn’t allow us to establish a geographic delimitation, under a qualitative perspective, the authors of this study decided to concentrate their attentions on posts linked to their original countries (Brazil and Spain), therefore, the posts in French and English were excluded from the research. This decision represented the scope in which the study will take place. We noticed, in the Portuguese posts, that a great extent of posts on X (former Twitter) had a link to Pula Muralha, a YouTube channel whose main author is a Chinese immigrant living in São Paulo, Brazil, at the time. In this channel, many users published personal comments directed to the author, Si Lao, known as Sisi, and her family, in a video where the youtuber talked about the campaign #IamNotAVirus.

Image 6. Post Example of comment in the channel «Pula Muralha»

Source: YouTube Channel «Pula Muralha».

In addition to the dissemination of the campaign through mainstream media, in Brazil, the campaign also had the engagement of the Chinese Embassy, through their profile on X (former Twitter), in support to the presence of the campaign creator in journalistic shows.

Image 7. Post by the Chinese Embassy in Brazil about the campaign

Source: Profile @EmbaixadaChina on X (former Twitter).

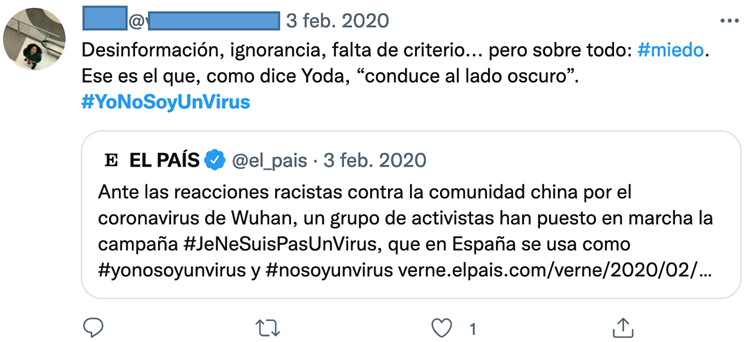

In turn, in the case of campaign posts written in Spanish and observed from Spain, even without the goal of a statistic representation, we identified, through social media monitoring, two movements that seem to stand out. On one hand, the reinforced use of the hashtag #YoNoSoyUnVirus with small personal commentary of people supporting the cause and the reinforcement of journalistic content about the campaign (Image 8). On the other hand, many digital micro influencers —users with up to 10 thousand followers (Primo et al., 2021)— with Asian origins appeared with similar posts supporting the campaign, with images holding a poster with the hashtag «YoNoSoyUnVirus», among which we highlight the profile of the Spanish lawyer and intercultural mediator of Chinese descent Antonio Liu (Image 9).

Image 8. Example of a X (former Twitter) post with the hashtag #YoNoSoyUnVirus

Source: X (Twitter.com).

Image 9. Post by the Spanish micro influencer Antonio Liu

Source: @antonioliuyang’s post on X (Twitter.com).

Guided by the campaign’s context and the presupposition derived from the first observation, this article has the goal of analyzing communication in a network of activists linked to the Chinese diaspora that sought to articulate anti-racist and anti-xenophobic narratives facing the discourses linking Coronavirus to the Chinese population in the Covid-19 outbreak. The analysis focused specifically in the processes of digital production of both campaigns — #EuNãoSouUmVirus shared on X (former Twitter) and YouTube, in Brazil, and #YoNoSoyUnVirus, shared mainly on X (former Twitter), in Spain— and developed from two dimensions extracted from the empirical material: (1) the emergence of racist and xenophobic narratives around a Chinese virus as an impulse towards transnational activism of the Chinese diaspora on social media; (2) the activism around the campaign #YoNoSoyUnVírus as an opportunity for political engagement and the confrontation of the conflict in the context of Chinese culture.

2. Literature review

The 1990’s marked the development of a field of theoretical reflection about migrant transnationalism that began to postulate the need for analysis that integrated space and conditions of origin and destination of migrants (Retis, 2018; Glick-Schiller et al., 1992; Vervotec, 2009; Guarnizo, 2004; Portes, 2004). In response to the so-called methodological nationalism, the studies on migrant transnationalism began to be interested in the ways the displacement of populations produced identity, social, financial and political dynamics in the in-between places of the societies of origin and residence, at the same time they transcend the moment of displacement. Glick-Schiller et al. (1992) proposed the notion of transmigrant for understanding the multiple, constant connections among international identities and borders that delimitate a migrant’s daily life and locates them in a space of multiple and simultaneous relations with more than one nation state.

Guarnizo (2004) coined the expression «transnational living» in order to signal that migrant transnationalism dynamics are not reduced to the economic impact of north-south money transfers in their original locations, but they are constituted with an intense symbolic flow of ideas, behaviors, identities and social capital that connects the countries of origin and residence of migrants. Portes (2004) reminds us, however, that the exercise of transnationalism does not always constitute a universal or regular practice amongst migrants, although it is recognized that the macroeconomic and social impacts generated by the actions of migrants cannot only be assessed by the numbers involved in these actions, but we must take into consideration the sum of regular transnational actions of activists, beyond punctual actions performed by other migrants. The majority of research on transnationalism still do not consider that migrants create organized spaces of one-way connection between places of origin and residence, but rather places that are composed by movements of continuous and contradictory deterritorialization and reterritorialization that come from the processes of globalization (Mezzadra, 2015).

Transnational actions of migrants can comprise from a money transfer and/or regular visits of these activists to their original countries for business investment, philanthropic work and organization of cultural events, to a direct intervention and participation in political and electoral processes in these countries. Tarrow (2010) reminds us, about this matter, that this participation does not exclude migrant nationalists that mobilize discourses of diaspora in order to, through the use of violence, destabilize or take down the government of their original countries, such as, for example, Croatians in Canada, Irish people in Boston and Kurdish people in Germany. Vervotec (2009) equally analyzes how migrants have been framing transnational spaces that reset the notion of time and belonging and allow the exercise of associativism and political action through transnational mobilizations that involve their fight for rights and recognition. Migrant mobilizations in the fight for rights and citizenship have been approached through different perspectives, among which, those associated to overseas citizen voting (OIivera & Cogo, 2017; Martínez, 2017), to return migration (Cogo & Santos, 2022), to the report of coup d’état in their origin countries (Cogo, 2019a; Almeida & Cogo, 2022) and the report of racism in their countries of residence (Cogo, 2019b).

In the field of political action, the Chinese diaspora, as pointed out by Zhao (2020), needs to be understood through singular traits and characteristics, as well as through their long centenary tradition, which dates back to the Ming Dinasty and requires a contextualization of the different moments in which Chinese mobility was related to political actions of the Chinese state. However, when dealing with the issue of political activism in Chinese diaspora, the author defends a view that allows us to understand the action of activist voices in the political sphere through more complex layers, not limited to the debate about democracy or other models of government, frequent in the global North literature and very narrow-minded.

In this sense, Tan et al. (2021) explain the singularities of transnational bonds of China and its diaspora, proposing levels of analysis based on three filters: economic, political and social; these filters, according to the authors mentioned, must be seen in the macro, meso and micro levels. Thus, they argue that the Chinese diaspora must be seen through a holistic perspective, not fragmented, but multi-dimensional. Therefore, they highlight how Chinese politics varied throughout the years regarding its diaspora, combining international and domestic perspectives in relation to themes like citizenship, through, for instance, the creation of visas for returning migrants who gave up their nationality in order to adapt to their country of residence (since Chinese legislation forbids double-citizenship), as well as talent recruiting and actions of soft power.

Following the same perspective, Liu and Benton (2016) argued about the importance of not creating a restrictive trap —as the one Zhao (2020) criticized— and analyzing the weight of the relationship between the diasporic country as a co-optation of the diaspora by the Chinese government or otherwise. In effect, the authors highlight the importance of transnational social players, among which, the so-called new migrants, as one of the elements that contribute for altering the structures and policies of their country, favoring improvements in the quality of life or generating economic benefits. However, the authors nuance that the transnational engagement of the Chinese diaspora must not be seen as based in a monolithic cause or feature. As the example of other migrant collectives studied by the transnational perspective, this engagement can be motivated by a variety of reasons or interests.

The activism of Chinese diaspora concentrated in this study is not oriented by the claim of a specific right in their original country —China—, but by the demand for recognition in the countries of residence, which involves the complaint and combat of racism and xenophobia related to the origin and nationality of migrants. Materialized in a discursive flow about the «Chinese virus» during the Covid-19 outbreak, this demand for recognition is similar to an ethical-political proposition in the shape described by Honneth (2013), to whom, in turn, the mutual intersubjective recognition of an individual identity is the ethical anchor which allows these subjects to feel respected and, consequently, be supported in the passing of their social interactions in multiple spheres. Therefore, the individual meaning of dignity —either under an ethical or political perspective— necessarily goes through the processes of identity recognition.

The reflections about the renovation of forms of political participation and mobilization of migrants and migratory collectives through the use of digital technology have aligned with the so-called epistemic agency and migrant autonomy, developed by authors like Lacomba Vázquez and Moraes Mena (2020) and Mezzadra (2012). It is an epistemological perspective that have contributed for the understanding of actions, strategies, fights and resistance of migrants, as well as their processes of intervention and transformation in different social, economic, cultural, artistic and political instances. The perspective of autonomy does not ignore the contradictions in the migrant mobilization, bearing in mind that the agency does not necessarily imply in processes of empowering migrants (Lacomba Vázquez & Moraes Mena, 2020).

In effect, Mezzadra calls attention to the tensions between structural forces and the subjective capability of action from migrants, claiming special attention to the need to «shed a light on subjective practices of negotiation and opposition to the power relations» (2012: 13), in specific contexts in which migratory dynamics can be observed.

Migrant transnationalism has been suffering readjustments through the processes of digitalization of communication and popularization of the Internet, especially due to the new dynamics of interaction, subjectivation and sociability constituted in the milestone of prominence of digital platforms managed by the so-called «big techs». In its condition of capitalist companies inserted into a market logic, these platforms have been operating, through their business models, to form a set of social relations through the offer of digital services and the organization of the dynamic of extraction, processing and treatment of personal and behavioral data that translate into algorithmic policies that aren’t always clear for user’s rights, while convenient to the interests of a global market centered in an asymmetrical power relationship (Zuboff, 2020; Véliz, 2021).

In the perspective of digital socio-technical networks as spaces of power, sociability and political action, authors such as Lago Martínez (2008) put in a critical perspective the optimistic view created by the work of Manuel Castells (2012) to nuance that the power asymmetries limit the political action of individual and collective authors, including migrants. However, the author recognizes that, although the political economy of digital platforms restricts the architecture of these networks, it also allows gaps that favor the articulation of political actions beyond national borders, especially through the uses of digital technologies that began to be incorporated, since the 1990’s, by movements of global resistance and social and cultural collectives, including migratory collectives. Lago Martínez (2008) calls attention to new organizational forms based on de-centralized and horizontal forms and in the collective work with the Internet’s support, for the internationalization of protest and the simultaneity of actions of resistance, emphasizing, still, the relevance that takes on the aesthetic and communicative dimension of political action, as well as the re-creation of local forms of cooperation and language.

In methodological terms, migrant transnationalism had initiated an important conceptual transition regarding the spaces where contemporary migratory experiences are developed, observed and studied, contributing to an emergence of the notion of «transnational social fields» which became central in migratory studies (Glick Schiller et al., 1992). For migratory studies regarding media and digital technologies, the reflections of Hine (2004), and Miller and Slater (2000) enabled the theoretical-methodological understanding of the Internet as a space of sociability and interactions that favors the formation and maintenance of social-communicational networks. The configuration, on the Internet, of a type of non-physical spatiality made migratory dynamics noticeable through connections, relations and networks that transcend the borders of nation states.

3. Methodology

The research methodology, of a qualitative matter, comprised in observation and collection of posts about the campaigns #EuNãoSouUmVírus and #YoNoSoyUnVirus, located in Brazil and in Spain, and shared on X (former Twitter) and YouTube, as well as the execution of semi-structured interviews with three creators and producers of these campaigns, two of them responsible for the campaign in Brazil, and the third responsible for the campaign in Spain.

In order to get to the proposed scope, as previously explained, we tracked the hashtags used in the campaigns, between January 15th, 2020, and March 15th, 2020, in their respective translations. Thus, we sought to identify the authors of the first posts, both in Brazil and in Spain, so we could identify the interviewees. An additional work of documentation, through the news published in the Brazilian and Spanish press about the campaign also allowed us to find the main names related to the campaign in its initial moments, in Brazil and in Spain. That way, we identified the Pula Muralha YouTube channel, in Brazil, and Antonio Liu, among others, in the Spanish case, as we previously showed in the introduction of this article.

It is important to highlight the contexts of production and dissemination of the campaigns in the countries we studied happened in different ways, even though the qualitative analysis of posts and the interviews we executed allowed us to evidence commonalities in the processes of production of both campaigns in different countries, suggesting the configuration of a transnational activism movement of the Chinese diaspora around the same mobilized global cause in the context of the Covid-19 outbreak.

For the analysis of the campaign production process, we made in-depth interviews in Brazil with Si Liao (known as Sisi), a 34-year-old Mandarin teacher from Wuhan that arrived in São Paulo in 2011 and Lucas Brand, a 34-year-old Brazilian journalist. Sisi and Lucas are married, live in São Paulo, created and promoted the campaign #EuNãoSouUmVírus in Brazil, even though Sisi, of Chinese descent, was the face and the public visible voice in the campaign. Prior to the production of the campaign, Sisi and Lucas created the YouTube channel Pula Muralha, which currently has 799 thousand subscribers, and that was essential in the creation and promotion of the campaign. In their YouTube profile (@pulamuralha), the channel is defined as:

[...] the biggest YouTube channel from a Chinese from China living in Brazil and publishing weekly videos to people interested in expanding their worldview and knowing new cultures through light, informative and fun content. Presented by Si Lao, Chinese (really, from China) and Mandarin teacher, and Lucas Brand, Brazilian journalist (really, from Brazil). We also are Pula Muralha, a company specialized in Chinese teaching for Brazilians and manager of the Chinese Club, the biggest Mandarin online course in Brazil (@pulamuralla, 2023).

In Spain, the interviewee was Antonio Liu, a 42-year-old coming from Beijing, China, who migrated with the family to a Spanish city in the countryside of the Valencia Province in 1990. Antonio currently resides in Madrid and is graduated in Law. With a diverse professional background, he works as a lawyer and business consultant on themes related to China, in addition to being a guest lecturer in universities and business schools to talk about China and international relations.

The script followed on the interviews with the three activists had six themes: 1) migratory trajectory; 2) professional background; 3) experiences of activism; 4) interactions between their country of migration (Brazil, Spain) – original country (China); 5) consumption and use of digital technology; 6) creation, production, circulation and consequences of the campaign #NãoSouUmVírus/#YoNoSoyUnVirus. The authorization of the interviewees for the use of the interview content and their names is registered in audio. The interviews, made through Zoom in October and November 2021, were conducted and, later on, transcribed, by the authors of the article. Both interviews were categorized and analyzed through the theoretical themes of the study and with the help of the software AtlasTi.

It is important to highlight that, through the objectives outlined in this article, namely, analyzing the campaign production process by the activists of Chinese diaspora in Brazil and in Spain, we mainly explored the data extracted from in-depth interviews with the addition of the analysis of publications about the campaign in digital platforms and on the Spanish and Brazilian press. In methodologic terms, we aligned to the proposition of online ethnography of authors like Hine (2015) and Winocur (2013) who defended a social-cultural approach that allows encompassing the diversity and perspective of the player for the reconstruction of the meaning in interactions and practices in digital environments through, for instance, the adoption of methodological strategies that mix observation and collection of digital traces derived from the interaction of players in the networks with the execution of interviews or focus groups with these players.

Guided by this objective, we, then, started to develop two routes of analysis on the campaign production in the two national contexts chosen, defined by the theoretical background and the material extracted by the empirical approach: (1) the emergence of racism and xenophobic narratives around a «Chinese virus» as an impulse for the transnational activism of Chinese diaspora on social networks; (2) the activism in the campaign #NãoSouUmVírus/#YoNoSoyUnVirus as an opportunity for political engagement and confrontation of the conflict in the context of Chinese culture.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Transnational activism of the Chinese diaspora

Both in Brazil and in Spain, the creation and promotion of the #NãoSouUmVírus/#YoNoSoyUnVirus campaign on social media was related to the experience of transnationalism by the creators of the campaign, especially through their uses of social media for the maintenance of bonds with family members or friends integrating the Chinese diaspora in their countries of origin (China) and their countries of residence (Brazil and Spain). Or, even, through the use of digital platforms and networks for an intercultural and transnational work related to the Chinese culture developed by them in their country of residence.

In the landmark of these transnational experiences marked by intercultural relations, the creators of the campaign experienced racist and xenophobic attacks that tried to associate Coronavirus and China during the Covid-19 outbreak especially through discursive flows related to the Chinese virus. These attacks were materialized in comments about the «Chinese virus» posted in different platforms such as, for example, the Pula Muralha YouTube channel or in interactions in which Antonio, Sisi and Lucas maintained with family members and friends on X (former Twitter), in message apps such as WeChat (with Chinese Family and friends), WhatsApp (with Brazilian family and friends), and in daily situations in interpersonal exchanges.

And, at least for me, I had one day there in a (WhatsApp) family group chat, one of these groups that has loads of cousins, loads of people. Someone sends something like «if you want to clear up a line in the bank, sneeze and say you came from China.» [...] I am reading this type of stuff and I saw people laughing afterwards. […] Then, I got in the middle of the discussion and said: «Look, this is offensive, remember? There are Chinese people in the family, ok? I am married to a Chinese woman, please have some respect. They are going through a tough time. What the Chinese people need now is solidarity, not jokes like that». After that, they understood and apologized. [...] The main thing about prejudice is that. Sometimes, it comes disguised as a joke. That normalizes a stereotype, prejudices (Lucas, interview).

Many people, especially from Latin America, had started to say the Chinese virus. I thought, then, if we don't do something on time, this will become the unofficial name. In fact, the name Covid-19 had not yet emerged; it was coronavirus, what was said. I saved the tweets very fondly and said: we have to do something! (Antonio, interview).

In addition to these initial experiences with the expression «Chinese virus», Sisi, Lucas and Antonio became aware of similar campaigns produced in other countries and in other languages, such as «I’m not a virus» and «Je ne suis pas um virus», being shared on social media. Antonio remembers that, in a WhatsApp friend group debating about the development of a campaign in Spain, people already knew about mobilization around «I’m not a virus» on social media. Sisi and Lucas said, in turn, they knew about a campaign happening in France, that was published on January 28th, 2020, by a Chinese student that was studying in France.

Image 10. Post published in France by a Chinese student holding a poster

Source: @ChengwangL’s post on X (Twitter.com).

A similar image with a handwritten poster in Portuguese and Spanish was used by the creators of the campaign in Brazil and in Spain and posted on social media —on YouTube, by Sisi, and on X (former Twitter), by Antonio— suggesting a transnationalization of the campaign as a result of their digital interactions with the initiative in France and in other countries, since Sisi, Lucas and Antonio told not to have direct contact with the creators of the same campaign in other countries. In the Brazilian and Spanish contexts, different digital technologies were used in the process of creation, production and circulation of the campaign that comprised the use of WhatsApp and platforms like X (former Twitter), Facebook, Instagram and YouTube.

Image 11. Images shared by creator in Brazil and in Spain

Source: Pulamuralha (YouTube) and @antonioliuyang (X).

Sisi, Lucas e Antonio worked towards the national redefinition of the campaign in Spain and in Brazil, initially through the translation to Spanish and Portuguese, reaffirming that transnational activism frequently turns to communicational strategies for the adaptation of political action to local and national contexts. «The rest of the World is with the ‘I’m not a virus’ campaign, with a poster, and we can Spanishize this campaign by putting the hashtag #NoSoyUnVirus, both for Spain and for the rest of the Spanish-speaking countries», said Antonio, bringing up the perception about the urgence of a political action that would focus on the possible impacts on the Chinese Community due to the expression «Chinese virus» going viral on social media. «And then we stop being called the Chinese virus because if there is a Chinese virus, we will have identity problems later, and it is going to rain many worse things than what we are going through.»

Discrimination based on phenotypic traits was also the perception that contributed for Antonio’s recognition of the influence that his Asian traits could have in relations that began to unfold between China and the Covid-19 pandemic.

It's not just Chinese; it's the entire immigrant group. No matter how Spanish I want to feel because I've been here for 30 years, my face will not change. This is something curious and a feeling, an identity of what is behind it (Antonio, interview).

In the Brazilian case, Sisi and Lucas saw the nationalization of the campaign as an opportunity of changing the narrative about the «Chinese virus» and deconstructing this stigmatizing view associating a virus to a nation and a nationality.

So, there was a lot of negative comments and we saw this campaign in France «I am not a virus». And it looked like this campaign was an easy way of saying that «I Look, it’s not about the Chinese people. It’s a virus that coincidentally appeared and was spread there. It’s a biological issue. This has nothing to do to a person, a nation, a citizenship, whatever» (Lucas, interview).

The creation of the campaign took on a collective dimension in Spain through Antonio’s initiative of creating a WhatsApp group inviting mostly people linked to the Chinese diaspora in Spain, Chinese immigrants or Spanish people with Chinese descent, who had an expressive platform on social media such as Chenta Tsai (@putochinomaricón), Quan Zhou (@gazpachoagridulce), among others, who had a strong presence on social media or in mainstream media.

Under that same collective perspective, the transnational activism led by Antonio was also marked by an individualizing perspective which, conformed by the logic of social media visibility, promotes the action of the so-called «digital intermediaries», as it is the case of influencers, in contrast with experts and information professionals linked to the mainstream media (Cesarino, 2021). In this case, they act as discursive authorities forged through the migrant identity (Huertas Bailén & Peres-Neto, 2020).

The participation of digital celebrities on the campaign resulted, to a great extent, in the transnational dimension of the previous work of Antonio in organizing events related to China and the Chinese community in the Spanish context. In his interview, he remembers his involvement in co-organizing two Chinese New Year editions in Spain, where he would gather people related to the Chinese community for two lectures. One of the lectures had the presence of Chinese digital influencers (Chinfluencers), who also worked as players, musicians, and multi-artists, and the other lecture included the participation of Spanish women who had visited China.

The profile that we were looking for, or that I once looked for, was people who had visibility. Chenta was participating in the Madrid Fashion Week and came out with his torso painted «I'm not a virus», Quan has millions of followers because she is a graphic novelist, and her impact was enormous. Both Susana and Paloma were journalists and knew how to write very well and knew how to speak to the press. With these profiles and visible faces, because there are many invisible people, I didn't want to be hidden. [...] And it was the profile that we were looking for. We did not have a group, but we were friends and had collaborated in other previous events (Antonio, interview).

When observing that the use of the term «Chinese virus» to make reference to Coronavirus was getting popular on Latin America, Antonio, making use of his contact list, created a WhatsApp group with different people, all of them linked to the Chinese diaspora and, as previously explained, with visibility on social media. Inside the group, members began to discuss about the risk of having «Chinese virus» being converted as the official name of Coronavirus, which wasn’t called Covid-19 at the time. As previously mentioned, «the production of a black-and-white picture with a poster with #NoSoyUnVirus, without smiling, with the goal of being a bit more dramatic», according to Antonio, marked the promotion of the campaign in Spain. The members of the group decided that that would be the tone of the campaign and the manifestation to be made on social platforms.

The image began to be shared simultaneously on X (former Twitter), Facebook and Instagram, initially through the initiatives of the members of the WhatsApp group aiming a more general support of people to the campaign, not only for those linked to the Chinese diaspora. «This was a Sunday afternoon. I remember February 2th, a Sunday afternoon, and suddenly, I went to eat. When I returned, I saw many notifications from people who gave likes and comments» (Antonio, interview).

The campaign in Spain was not executed with a previous, well-made plan, but it was developed and formulated as the promotion went on. Characteristic of many experiences of digital activism, this procedural implementation of the campaign is also related, in Antonio’s view, to pragmatism being one of the traits of Chinese culture.

That is to say, we don't have to plan anything; we execute it, and then we fix it ongoing […] We said this «sobre la marcha» in Spanish, which means we are going to look while walking; it was just like this expression, let's not stay here looking or thinking that we are going to do, we are going to continue walking. Note that we are pragmatic about this (Antonio, interview).

Unlike the Spanish campaign, the development of the Brazilian campaign #EuNãoSouUmVírus did not initially count with the participation of digital celebrities, but it was propelled through the initiative of Pura Muralha creators, through the publication of eleven videos about China that gained a total of 2.300.000 views. A few unedited videos were composed of videos shot in China by Sisi and, in Brazil, by Lucas. In addition, they shared a series of videos in which Sisi and Lucas ate Scorpion skewers, or even talked about dog meat in China. «There were issues, at times classic preconceptions, dog meat [...] Scorpion skewer. And I think we end up, at times, spreading these stereotypes», Lucas said.

At the time that these videos were produced, alarming news about a disease in China, where Si Lao’s family lived in and went through a confinement period, began to arrive in Brazil. These news, as we mentioned earlier, began to fuel the dissemination of a series of fake news and racist and xenophobic remarks inside Lucas’ WhatsApp family group chat. Among these fake news, Lucas remembers an image of an artistic manifestation in Germany in which many people fell on the ground, and it was shared suggesting that «people are falling ill in China and dying of Covid».

These situations motivated Sisi and Lucas to create and share a group of videos about China and Covid-19 in the YouTube channel addressing, among others themes, the Coronavirus situation in China, fake news on Covid-19 and the bat, as well as clarifying the relation between the Covid-19 transmission and bats.

We called a biologist to join in our conversation. Transmit Covid? No, transmits virus. Because Covid itself we don’t know exactly what it is. We made a video talking about the video of Chinese people falling. And these were videos that took a lot of work for us. Why? Because there’s a lot of fake news being shared on the Internet. Until you locate the real source and learn about what’s really going on, it takes time and effort (Lucas, interview).

Even though they had the intention, according to Lucas, of clarifying fake news surrounding Coronavirus, the videos posted in the channel were de-monetized by YouTube. «Maybe they should have raised monetization in these videos because we were educating people, bringing facts, but we ended up being penalized» (Lucas, interview).

It is important to highlight that, in Brazil, the journalists Rudnitzki, & Scofield (2020), from the Public Agency, an investigative journalism ornaization without lucrative goals, analyzed 94 thousand tweets with the hashtag #VirusChines (Chinese virus) and, in August 2021, they publicly shared that bots were responsible for putting the hashtag on X’s (former Twitter) trending topics and using it for calling Tweetathons, in addition to sharing through WhatsApp groups for supporters of the former president Jair Bolsonaro.

The initial campaign production, according to Sisi and Lucas, was influenced by yellow activism groups in Brazil which had contact with the deconstruction of a few specific stereotypes built around Asians in Brazil, mainly those related to the idea that «Brazilians have that the Asian is always someone who aces tests, steals your spot in an university, Asians are nerds. And I guess that influences a lot in the childhood and adolescence of immigrants and Asians born in Brazil» (Lucas, interview).

According to Sisi and Lucas’ interview, the different negative comments generated by the videos about Coronavirus and China published on the Pula Muralha channel, interactions that were rarely generated in the channel at the moment, aligned with the contact with the French campaign, motivated the promotion of the campaign that was marked by the publication of a video in the channel, presented by Sisi, and title «Eu não sou um vírus» that got 87,000 views in less than six months after its publication.

4.2. Activism as an opportunity for political engagement

Additionally, the creation of these two campaigns was marked by another issue of techno-cultural nature highlighted by its creators, even though it takes on distinct configurations in the two national contexts —Brazil and Spain. According to Antonio, the work in the campaign allowed him to take on a position of activist that he previously rejected and that, in his perspective, is linked to a cultural trait that marked his upbringing in the context of a Chinese Family: avoiding confrontation and to pursuing harmony. Antonio attributes that to the fact that, for a long time, he had not recognized the micro aggressions he received when he attended a school in a small town in Spain and was bullied or derogatorily called «Chinese» by colleagues.

You know that the Asians, in quotes, are not problematic. We seek harmony over confrontation […] I grew up with this and was educated in this way at home. I remember some situations when I was little at home […]. Either you run away, or you face it. Well, the majority of Chinese people, and I dare say, to speak with representation or many people, have chosen to flee, to run away from that path. That is not the most straight; instead of facing society, school, and parents of the child who bullies, well, you go off on a tangent […] (Antonio, interview).

Before the Coronavirus period and the production of the «#NoSoyUnVirus» campaign, Antonio had rejected an invitation to shoot a video about racism against the Chinese community that would be played in a protest. He remembers the reason he rejected that invitation was the fear of publicly take on a political stance that could result in a counterproductive public exposure in different fields, including the professional field, resulting in a possible loss of clients for business consulting.

I thought that all of this being an activist was going to harm me; I was going to lose clients […] because companies don't like, they don't want people who get involved in social problems. What about all this, it has changed a lot! On the one hand, the way companies think has changed a lot. On the other hand, I have changed my way of thinking, and above all, because of the environment, the pandemic, which was the decisive moment that began with the «I am not a virus» campaign, and I said ok, right now they are blaming China for what is happening. Although I don't live in China, having Asian features is already influencing us in some way, in a pejorative way. Then we meet via WhatsApp, we create a group and we call people who have a little more visibility on social media, especially in the Spanishized Western (Antonio, interview).

In Sisi and Lucas’ case, on the contrary, it was the production of a «less combative and more inviting campaign», since they observed that, even the content or news that sought to share preconceptions and discrimination against China ended up having an offensive bias. The statement of a student in the Mandarin course about the emotion of watching a video about Chinese people in quarantine motivated them to invite people to send positive messages, of solidarity and encouragement to the Chinese population through the production of an inaugural video of the campaign «#NãoSouUmVírus», published on the Pula Muralha channel on YouTube and that, as previously mentioned, had 87 thousand views. In the video description, we see them inviting the channel subscribers to engage with the hashtag «#NãoSouUmVírus».

It can be a picture of you in the feed or in Stories. Just mention me @pulamuralha and use the hashtag «#EuNaoSouUmVirus». You can also leave a comment here in the video! I am going to select a few comments to translate to Chinese and show to my parents, in addition to publishing in a special page so Chinese people all over the world can see your support. And if you don’t have an Instagram, no problem, you can send me a picture via e-mail (@pulamuralha on YouTube).

The perspective of the creators of the Brazilian campaign converges less with the tension of «absence of confrontation» as a dimension of Chinese culture and more towards the techno-cultural confrontation of the algorithm policy that is the base of the network architecture structured in polarization. However, in both cases, there is a recognition of their own identity that base a political action, in the shape of an ethics of recognition exposed by Honneth (2007) which links to a digital activism as opportunity for political engagement.

5. Final considerations

The analysis of the production of the campaign «#EuNãoSouUmVirus»/ «#YoNoSoyUnVirus» in two national contexts —Brazil and Spain— enabled us to bring up four final reflections about the transnational activism of the Chinese diaspora in digital networks in this article.

First, the experiences of racism and xenophobia in the migratory trajectory of the campaign creators in Brazil and Spain —before and during the Covid-19 pandemic— operated as a mediation for the creation of a campaign already in circulation in other national contexts, such as France. However, previous experience related to using social media as a content creator can also be relevant.

The territorial transversality enabled by the digital activism of Chinese diaspora also evidenced the exercise of a transnationalism that articulated Western cultural spaces (Brazil-Spain) and Eastern (China). Therefore, as a second aspect, the studied campaign was an opportunity for the political activism of the Chinese diaspora through the engagement of their proponents in an anti-racist and anti-xenophobic fight based on the recognition of cultural diversity.

Thirdly, the analysis results equally led to reflections on the transience of digital activism and the limits it can impose on the fight for (ethical and political) recognition of cultural diversity. Although with nuances, in both contexts, the campaign indicates a similar trend of promoters in a political struggle for recognition as a spin-off of their digital activities. Also, achieving cultural diversity as an egalitarian project is not a campaign's goal or further consequence. Legitimately, participants were battling against the xenophobic hate speech that fueled the campaign. However, it is a sign of the reach of this sort of digital activism.

In the field of consumption, finally, the campaign analyzed here aligned with short-term and ephemeral loyalties which characterize many of the experiences of political activism in a digital environment. In the field of production, however, the approximation with the perspective of actors of the Chinese diaspora in Brazil and in Spain allowed us to build clues about the impact of this activist micro experience in personal perceptions about their cultural, political and migratory trajectories. In Antonio’s case, these perceptions were translated into the questioning of how the absence of confrontation of the Chinese culture marked his migratory trajectory, as well as the recognition of the fear of taking on activism for the Chinese diaspora. In Sisi and Lucas’ case, as they affirmed on the interview, the campaign motivated their desire to expand migrant transnationalism, investing on digital productions about Chinese immigrants in Brazil and contributing to the project of language teaching by refugees created by the NGO Adus in São Paulo.

References

Ahijado, M. (2020, May 10). «No soy un virus»: los jóvenes de origen chino se rebelan contra el racismo en España. El País. http://tinyurl.com/4x9tkr43

Almeida, G., & Cogo, D. (2022). Redes sociocomunicativas e ativismo transnacional de bolivianos no Brasil no contexto do golpe de estado na Bolívia. In Silva, T. et al. (Eds.). Redes digitais e culturas ativistas 2: mídia, cultura e participação (pp. 149-174). Clea Editorial. https://tinyurl.com/unmsd95u

Castells, M. (2012). Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. Polity.

Cesarino, L. (2021). Pós-verdade e a crise do sistema de peritos: uma explicação cibernética. Ilha Revista de Antropologia, 23(1), 73-96.

Ciszek, E. L. (2016). Digital activism: How social media and dissensus inform theory and practice. Public Relations Review, 42(2), 314-321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2016.02.002

Cogo, D. (2019a). Brazilians in Spain: communication and transnational activism in a context of economic-political crisis. Communication & Society, 32(4), 223-238. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.32.36763

Cogo, D. (2019b). Communication, migrant activism and counter-hegemonic narratives of Haitian diaspora in Brazil. Journal of Alternative & Community Media, 4(3), 71-85. https://doi.org/10.1386/joacm_00059_1

Cogo, D., & Rodríguez Santos, D. (2022). Precarious Migrants in a Sharing Economy| #Nosomosdesertores: Activism and Narratives of the Cuban Diaspora on Twitter. International Journal Of Communication, 16(23), 5603-5625. https://tinyurl.com/2uuspf4a

Gerbaudo, P., & Treré, E. (2015). In search of the ‘we’ of social media activism: introduction to the special issue on social media and protest identities. Information Communication and Society, 18(8), 865-871. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1043319

Glick-Schiller, N., Basch, L., & Szanton Blanc, C. (1995). From immigrant to transmigrant: theorizing transnational migration. Anthropological Quarterly, 68(1), 48-63. https://doi.org/10.2307/3317464

Guarnizo, L. E.

(2004). Aspectos económicos del vivir transnacional. Colombia Internacional,

59, 12-47.

https://doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint59.2004.01

Hine, C. (2015). Etnography for the internet - embedded, embodied and everyday. Bloomsbury.

Honneth, A. (2013). Reconhecimento. In Canto-Sperber, M. (Ed). Dicionário de Ética e Filosofia Moral (pp. 885-889). Editora Unisinos.

Honneth, A. (2007). Disrespect: the normative foundation of critical theory. Polity Press.

Huertas Bailén, A., & Peres-neto, L. (2020). Migrantes que se autoproclaman autoridades discursivas: ¿Qué pasa en Venezuela? Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, 124, 147-169. https://doi.org/10.24241/rcai.2020.124.1.147

Lacomba Vázquez, J., & Moraes Mena, N. (2020) La activación de la inmigración. Migraciones - Revista del Instituto Universitario de Estudios sobre Migraciones, 48, 1-20. http://tinyurl.com/yutwxm3y

Lago Martínez, S. (2008). Internet y cultura digital: la intervención política y militante. Nómadas, 28, 102-111. http://tinyurl.com/5fppb39m

Liu, H., Benton, G. (2016). The «Qiaopi» Trade and Its Role in Modern China and the Chinese Diaspora: Toward an Alternative Explanation of «Transnational Capitalism». The Journal of Asian Studies, 75(3), 575-594. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911816000541

Martínez, M. J. (2017). Prácticas mediáticas y movimientos sociales: el activismo trasnacional de Marea Granate. Index Comunicación, 7(3), 31-50. http://tinyurl.com/47trn9y6

Mezzadra, S. (2015). Multiplicação das fronteiras e práticas de mobilidade. REHMU – Revista Interdisciplinar de Mobilidade Humana, 23(4), 11-30. https://bit.ly/3ekeTKy

Mezzadra, S. (2012). Capitalismo, migraciones y luchas sociales. La mirada de la autonomía. Nueva Sociedad, 237, 159-178. http://tinyurl.com/mjutsfy6

Miller, D., & Slater, D. (2000) The Internet: an ethnographic approach. Routledge.

Olivera, M., & Cogo, D. (2017). Transnational activism of young Spanish emigrants and uses of ICT. In Luppicini, R., & Baarda, R., (Eds.). Digital media integration for participatory democracy (pp. 155-187). IGI Global.

Primo, A., Matos, L., & Monteiro, M. C. (2021). Dimensões para o estudo dos influenciadores digitais. Editora UFBA. http://tinyurl.com/yu4hyts2

ReasonWhy.es. (2020). La campaña #NoSoyUnVirus combate los prejuicios derivados del coronavírus. http://tinyurl.com/578hvf59

Rudnitzki, E., & Scofield, L. (2020, March 20). Robôs levantaram hashtag que acusa China pelo coronavírus. Agência Pública. http://tinyurl.com/yccawyy8

Sierra, F., & Gravante, T. (2017). Tecnopolítica en América Latina y el Caribe. Ciespal.

Tan, Y., Liu, X., & Rosser, A. (2021). Transnational linkages, power relations and the migration–development nexus: China and its diaspora. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 62(3), 355-371. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12323

Tarrow, S. (2010). El nuevo activismo transnacional. Hacer.

Véliz, C. (2021). Privacidad es poder. Debate.

Vertovec, S. (2009). Transnationalism. Routledge.

Winocur, R. (2013). Etnografías multisituadas de la intimidad online y offline. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 3, 7-27. https://tinyurl.com/yxec57z9

Zhao, M. (2020). Chinese Diaspora Activism and the Future of International Solidarity. Made in China Journal, 5(2), 97-101.

Zuboff, S. (2020). The age of surveillance capitalism. The fight for a Human Future at the new frontier of power. Public Affairs.