index●comunicación | nº 14(2) 2024 | Pages 33-55

E-ISSN: 2174-1859 | ISSN: 2444-3239 | Legal deposit: M-19965-2015

Received on 21_02_2024 | Accepted on 10_06_2024 | Published on 15_07_2024

DISSEMINATION STRATEGY

OF SPANISH FACT-CHECKING AGENCIES ON THEIR ‘WHATSAPP’ CHANNELS

ESTRATEGIA DE DIFUSIÓN DE LAS AGENCIAS

DE VERIFICACIÓN ESPAÑOLAS EN SUS CANALES

DE ‘WHATSAPP’

https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/14/02Estrat

Alejandra Tirado García

Universitat Jaume I de Castelló (España)

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5947-7215

Laura Alonso-Muñoz

Universitat Jaume I de Castelló (España)

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8894-1064

This work is linked to RED2022-134652-T, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/ and “ERDF A way of making Europe” and to the project with reference 101126821-JMO-2023-MODULE (DISEDER-EU) funded by the European Executive Agency for Education and Culture (EACEA), belonging to the European Union

![]() To

quote this work: Tirado García, A. and Alonso-Muñoz, L.

(2024). Dissemination Strategy of Spanish Fact-Checking Agencies on their Whatsapp

Channels. index.comunicación, 14(2), 33-55. https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/14/02Estrat

To

quote this work: Tirado García, A. and Alonso-Muñoz, L.

(2024). Dissemination Strategy of Spanish Fact-Checking Agencies on their Whatsapp

Channels. index.comunicación, 14(2), 33-55. https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/14/02Estrat

Abstract: The objective of this research is to understand the dissemination strategy employed by Spanish fact-checking agencies through their WhatsApp channels. Specifically, it analyses the theme and function of the publications, the type of misinformation verified, and the interaction and multimedia presence. Quantitative content analysis is used to analyse the 258 messages published by Newtral, Maldita, and EFE Verifica on their WhatsApp channels over two months. The results show some interesting findings. Firstly, it is noteworthy that Newtral and Maldita have a regular publication frequency, but not EFE Verifica. Secondly, the conflict between Israel and Palestine dominates a large portion of the verifications by Newtral and EFE Verifica. In contrast, Maldita focuses on informing about topics related to science and technology or politics. Thirdly, it is highlighted that only Maldita seeks to promote real interaction with users through reactions. These findings provide insights into the use of newly created WhatsApp channels by fact-checking agencies.

Keywords: Journalism; Disinformation; WhatsApp channels; Fact-checking.

Resumen: El objetivo de esta investigación es conocer la estrategia de difusión que emplean las agencias de verificación españolas a través de sus canales de WhatsApp. Concretamente, se analiza el tema y la función de las publicaciones, el tipo de desinformación que se verifica y la interacción y la multimedialidad presente. Para ello se emplea el análisis de contenido cuantitativo sobre los 258 mensajes publicados por Newtral, Maldita y EFE Verifica en sus canales de WhatsApp durante dos meses. Los resultados muestran algunos apuntes interesantes. En primer lugar, destaca como Newtral y Maldita tienen una frecuencia de publicación bastante regular, pero no EFE Verifica. Segundo, el conflicto entre Israel y Palestina copa gran parte de las verificaciones de Newtral y EFE Verifica. En cambio, Maldita se dedica a informar sobre cuestiones relacionadas con la ciencia y la tecnología o política. En tercer lugar, destaca como sólo Maldita busca fomentar una interacción real con los usuarios a través de las reacciones. Estos hallazgos aportan conocimiento sobre el uso que realizan las agencias de verificación de los recién creados canales de WhatsApp.

Palabras clave: Periodismo; Desinformación; Canales de WhatsApp; Verificación.

1. Introduction

The emergence of the Internet, the popularization of social media as informational tools, and the redefinition of the public sphere, among other factors, have multiplied the volume and reach of information directed at citizens. Currently, users have constant and unlimited access to content from all kinds of sources, some of which provide accurate information, while others disseminate fake or erroneous news. In this context, there has been an increase in the discredit of traditional media (Salaverría & Cardoso, 2023), and a significant rise in the misinformation to which citizens are exposed (Casero-Ripollés, Doménech-Fabregat & Alonso-Muñoz, 2023). Information disorders circulate false or misleading content created, presented, and disseminated with the aim of obtaining economic profit and/or intentionally deceiving the public (European Commission, 2019). The exposure to this type of content seriously undermines the legitimacy of institutions and has strong democratic consequences (Bennet & Livingston, 2018). According to the First Study on Disinformation in Spain, 95.8 % of the population identifies the phenomenon of disinformation as a serious social problem (Uteca, 2022).

Given this scenario, data verification has gained special prominence in recent years, a journalistic discipline aimed at guiding citizens on the credibility of online content (Brandtzaeg, Følstad & Chaparro Domínguez, 2018) and promoting truth in public speech (Humprecht, 2020). While the first initiative of this kind dates to 1995 with Snopes.com (Graves, 2016), it has been over the last decade that most projects aiming to combat the phenomenon of disinformation have proliferated. These have spread worldwide, gaining momentum from 2016, when the Brexit referendum took place in the United Kingdom and Donald Trump's first presidential election campaign took place (Blanco-Alfonso, 2019). Since then, numerous journalistic initiatives have been dedicated to fact-checking (Vázquez-Herrero, Vizoso & López-García, 2019), becoming the most important variant of journalism in the digital age (López-Pan & Rodríguez-Rodríguez, 2019) with 391 active initiatives worldwide (Stencel et al., 2022). Furthermore, 50 countries have data verification projects linked to the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), which brings together 91 registered platforms, both dependent on media outlets and news agencies, as well as independent ones (Cherubini & Graves, 2016).

Fact-checking agencies have an important role in literacy so that both information professionals and citizens learn to distinguish false from true content and stop contributing to its virality (Buchanan, 2020). These agencies not only have to ensure the accuracy of the information they verify and the quality of the messages they disseminate, but also present them attractively and ensure they reach a massive audience through their digital channels. To date, fact-checkers had opted for X (former Twitter) and Facebook as the most used channels, followed by Instagram and YouTube (Dafonte-Gómez, Míguez-González & Ramahí-García, 2022), and recently also TikTok (Sidorenko-Bautista, Alonso-López & Giacomelli, 2021). However, in Spain, in early September 2023, some fact-checking agencies made the leap to instant messaging mobile services and launched their own WhatsApp channels. This is the case of Maldita, Newtral, and EFE Verifica, Spanish agencies signatories of the IFCN codes.

Although previous literature has warned of the importance of instant messaging mobile services in combating disinformation (Dafonte-Gómez, Míguez-González & Ramahí-García, 2022), there are still no scientific studies on the subject. In this sense, the present research constitutes a descriptive approach to how Spanish fact-checking agencies use WhatsApp channels to disseminate their content. Although it is an exploratory study, the analysed cases are useful to observe the different formulas used by fact-checkers to reach the audience.

2. Literature review

Disinformation has become a problem threatening the legitimacy of contemporary democracies (Bennett & Livingston, 2018) and has consequences on the democratic quality of our societies. It is a phenomenon that has been present throughout the history of communication, especially during the times of armed conflict (Bloch, 1999). In the first half of the 20th century, Nazism (Doob, 1950) and Soviet communism (Lasswell, 1951) recurrently employed the planned dissemination of false messages to confuse the adversary. Subsequently, during the Cold War, this practice became widespread, extending to a large number of countries worldwide. In the 1990s, this practice was further enhanced with the arrival of the technological revolution and its impact grew exponentially to the point in which, in 2017, the Oxford dictionary chose the term «fake news» as the word of the year (Vázquez-Herrero, Vizoso, & López-García, 2019). Since then, a spiral of disinformation previously unseen has been witnessed (Salaverría & Cardoso, 2023), which worsened even more with the COVID health crisis in 2019 (Zunino, 2021; León et al., 2022), leading to what the World Health Organization (WHO) has termed an «infodemic» (WHO, 2020). Additionally, the outbreak of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine in 2022 has also contributed to the proliferation of hoaxes aimed at destabilizing the adversary (Fernández-Castrillo & Magallón-Rosa, 2023).

Presently, we are facing a communicative ecosystem marked by information disorders (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017) that «drive the production and massive circulation of deliberately false information, non-harmful erroneous information, and malicious information» (Casero-Ripollés, Doménech-Fabregat & Alonso-Muñoz, 2023: 4). Wardle and Derakhshan (2017) point out different variants of disinformation. Firstly, the one known as «misinformation» (Burnam, 1975) refers to inadvertent errors that journalistic organizations may make when preparing information, such as incorrect data or misattributions resulting from involuntary confusions inherent in communicative processes. The second modality, «malinformation» (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017), refers to truthful information whose dissemination is unethical because it is strategically used to cause harm. Finally, the third and the most worrying variant for Western democracies, due to its rapid spread, corresponds to deliberate falsehoods or hoaxes. «Disinformation» refers to fabricated false content intentionally disseminated. This variant grew following the COVID-19 pandemic with social media and instant messaging services as the main stage, to the extent that companies such as WhatsApp, Facebook, X (former Twitter) and Google took measures to reduce their users' overexposure to unverified content (Salaverría et al., 2020).

Although the growth of disinformation is not solely attributable to technology, the existence of a wide range of falsification practices on digital platforms also raises alarms about the existence of bots, imposter profiles, or the so-called «astroturfing», a form of falsification that involves the planned coordination of multiple social media accounts to artificially create thematic trends (Arce-García, Said-Hung, & Mottareale-Calvanese, 2022; Chan, 2022). Furthermore, recent advances in Artificial Intelligence have also exacerbated this phenomenon insofar as they allow the mass fabrication and dissemination of so-called «deepfakes» videos and audios that reproduce false images and sounds, but with a high degree of realism (Casero-Ripollés, 2024). According to Fernández-Castrillo and Magallón-Rosa, the relationship between AI and disinformation is particularly sensitive when discussing «moments of special informational and emotional sensitivity; the culture of outrage and clickbait can potentiate and amplify their harmful effects» (2023: 26).

2.1. To combat disinformation in the digital environment

The exponential growth of disinformation in recent years and the loss of quality and credibility of media outlets have heightened concerns about the dissemination of false information (Bachmann & Valenzuela, 2023). This has led to data verification, a basic practice, and a sine qua non condition of journalistic production, gaining prominence within the current information ecosystem as a tool to combat fake news (Graves & Cherubini, 2016; Guallar et al., 2020), especially in European and North American journalism (Vázquez-Herrero, Vizoso, & López-García, 2019). This practice is popularly known as fact-checking and consists of «the systematic practice of verifying the statements made by public figures and institutions and publishing the results of the process» (Walter et al., 2020: 73). Data verifiers are considered non-partisan bodies whose objective is to provide truth (Humprecht, 2020) and improve citizens' access to information (Palau-Sampio, 2018; Nyhan & Reiffler, 2015).

Between 2012 and 2017, there was significant growth in fact-checking, resulting in the creation of over a hundred national and international journalistic verification organizations (Alonso, 2019; Ufarte, Peralta, & Murcia, 2018). Leading media outlets such as the BBC, The Washington Post, Le Monde, or the EFE agency, among others, have created their own fact-checking spaces for users to verify whether information is true or false (Vázquez-Herrero, Vizoso, & López-García, 2019). Similarly, newspapers like Público.es have also incorporated computer tools like TjTool, which show users the tracking of news published by the media (Terol & Alonso, 2020). Institutionally, verification groups have also been created, such as the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), which promotes organizations dedicated to information verification in Europe, and the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) of the Poynter Institute in the United States, which promotes the excellence of verifiers with codes of good practices to contribute to public discourse through transparency and accountability. In Spain, there are currently five consolidated journalistic data verification organizations, three of them independent—Maldita.es, Newtral, and Verificat—and two belonging to state media—EFE Verifica and Verifica RTVE. All are associated with the IFCN and exhibit high levels of compliance with its principles (Moreno-Gil & Salgado-de Dios, 2023).

The need to reach society is an intrinsic part of the raison d'être of fact-checkers so that their debunkings reach affected individuals (Humprecht, 2020). In this regard, verification organizations have incorporated social media into their content distribution strategies because, among other reasons, it is not necessary to invest a large amount of money, and they can involve users in social conversation regarding the verifications they publish (Brandtzaeg, Følstad, & Chaparro-Domínguez, 2018). Thus, they offer users the possibility to share content either to spread their debunking or to generate traffic to their websites. While presence, regularity in content publication, and interaction on social media are essential aspects of their activity development, recent studies have shown that the presence on these platforms is more prominent in the case of independent fact-checkers than those linked to media outlets, as the latter tend to use the media's own channels (Dafonte-Gómez, Míguez-González, & Ramahí-García, 2022).

On platforms like X (former Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, or TikTok, fact-checkers disseminate their content and multiply its spread through interactions with their contacts in the same spaces where misinformation circulates (Margolin, Hannak, & Weber, 2018; Sidorenko-Bautista, Alonso-López, & Giacomelli, 2021). In this regard, some studies have indicated that the narrative format of the debunking on these platforms does not influence the user's attention to a greater or lesser extent (Ecker et al., 2020; Huang & Wang, 2022). In this line, according to Bachmann and Valenzuela (2023), it does not matter if verifications have multimedia elements or attractive stylistic resources, despite agencies' efforts to find optimal correctives (Walter et al., 2020). Conversely, Sidorenko-Bautista, Alonso-López, and Giacomelli (2021) point out that, on platforms like TikTok, verification journalism has a place and it will endure «as long as it seeks and develops new narrative skills, taking into consideration the constant evolution experienced by the platform regarding trends and user groups» (2021: 107). To achieve this, verifiers work to adapt content to the narrative style of this social media, using vertical video, TikTok's editing tools, and formats like micro-tutorials, although interaction with the audience is lacking (Elizabeth & Mantzarlis, 2016). Regarding the most popular topics of verifiers on TikTok, political topics stand out, as well as health, climate, and technology (Sidorenko-Bautista, Alonso-López, & Giacomelli, 2021).

Alongside social media, the digital environment offers new tools for the activity of fact-checkers. This is the case of WhatsApp channels, recently created, which have emerged strongly and currently constitute one of the usual communication channels between media outlets and citizens. It is a new feature of the platform that allows the dissemination of public messages to large audiences, instantly reaching recipients. Communication developed in these channels is unidirectional since subscribers can forward messages but cannot chat or leave comments. Users can react to content using emojis, but it is the channel owner who decides which ones are available. Additionally, if subscribers have privacy enabled, no one can see their phone number.

In Spain, WhatsApp channels were launched in mid-September 2023 and only existed in Singapore and Colombia until then. Since their creation, numerous media outlets have incorporated them into their communication strategies, including some verification agencies such as Newtral, Maldita, and EFE Verifica, with a notable reception from the audience in terms of the number of subscribers. Through these channels, they aim to ensure that messages sent reach users' mobile devices directly without the need to open the application or search for a specific channel. Therefore, it is particularly relevant to understand the content distribution strategy used by Spanish verification agencies on WhatsApp channels.

3. Data and Method

The objective of this research is to understand the dissemination strategy employed by Spanish fact-checking agencies on their WhatsApp channels. Specifically, the following specific objectives are outlined:

1. To identify the topics of the messages shared by Spanish fact-checking agencies on their WhatsApp channels.

2. To analyse the types of sources included in the messages shared by Spanish fact-checking agencies on their WhatsApp channels.

3. To examine the function of the messages shared by Spanish fact-checking agencies on their WhatsApp channels.

4. To study the types of misinformation verified by Spanish fact-checking agencies on their WhatsApp channels.

5. To analyse the interaction and multimedia presence in the WhatsApp channels of Spanish fact-checking agencies.

To achieve these objectives, messages published between October 15th and December 15th, 2023, by three Spanish fact-checking agencies—Maldita, Newtral, and EFE Verifica—have been selected. The sample selection primarily responds to two reasons. The first is that these three fact-checking agencies are the most relevant in Spain. The second is that WhatsApp channels were opened in Spain on September 13th. However, since not all media outlets created the channel on the same day, to equalize the sample and make it comparable, October 15th has been established as the date when the channels of the three selected verification platforms had already begun to publish content. The sample of this research consists of 258 messages (124 from Newtral, 115 from Maldita, and 19 from EFE Verifica).

To address the objectives outlined in this research, the technique of quantitative content analysis is employed, which allows for the objective and systematic examination of the content of the analysed messages (Bardin, 1996). The analysis model created for this research collects information on 7 variables, whose categories are mutually exclusive, and therefore each message can only be classified into one of them (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of the analysis model

|

Topic |

Function |

Type

of |

Type of sources |

Type

of |

Type of multimedia |

Type of link |

|

Science and technology |

Inform |

Joke, satire or parody |

Official |

React

|

Photo

|

Own web |

|

Economy |

Advise |

Exaggeration |

Professional |

Share

|

Video

|

External web |

|

Health |

Disclaimer |

Decontextualization |

Alternative |

Send information to verify |

GIF

|

Own Social Media accounts |

|

Politics |

|

Fabricated |

Others |

|

Screenshot

|

Extern Social Media accounts |

|

Environment |

|

Manipulation of images or videos |

|

|

Link

|

Phone number |

|

Culture |

|

Reuse of images or videos |

|

|

Other |

Other |

|

Immigration |

|

Others |

|

|

|

|

|

Territorial Policy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Food |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

International conflicts |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Terrorism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disinformation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Security |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Religion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

International politics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Social |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Incidents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Monarchy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Own elaboration.

The sample has been manually captured directly through the WhatsApp channels of the three selected fact-checking agencies. It has been analysed by two coders who conducted a pre-test on 10 % of the messages (n = 26), obtaining high Krippendorff's Alpha values (Hayes & Krippendorff, 2007) for all variables (α>0.90). The data have been processed using the statistical package SPSS (v.28).

4. Results

4.1. Frequency of publication and characteristics of the WhatsApp channels of Newtral, Maldita, and EFE Verifica

The WhatsApp channel of Newtral has 16,985 followers[2] and presents itself as a platform that «defends facts against misinformation and hoaxes» and helps «understand what is happening without noise or ideologies». During the analysed period, it is observed to have an irregular publication frequency, with peaks of activity where there are days when it shares up to six messages and others where it does not publish anything (Figure 1), disseminating a total of 124 messages. The contents published by Newtral are mainly characterized by containing little text. They display a headline, sometimes complemented with a subtitle, and usually contain a link to their website for further information. The messages they use to verify information often contain the same elements: an image with the word «fake» on top and two red crosses at the beginning of the text.

Maldita has 27,668 followers[3]. In the presentation of its channel, it indicates that users can find «debunking of hoaxes and misinformation that reaches your mobile phone and useful information for daily life». Additionally, it complements the profile description by adding its motto («Journalism so you won't be fooled») and a link to its website. The publication frequency between October 15th and December 15th is high and quite regular (Figure 1). Although some peaks of activity can be observed, the fact-checking agency has published at least one content almost every day, reaching a total of 115 messages. The contents shared by Maldita are structured in the same way as on its website, thus using the same captions and sections. This makes them easily recognizable by users who consult the digital version of the fact-checking platform. They are usually long messages with substantial text, accompanied by various emojis and a link to their website.

Figure 1. Publication frequency of Newtral,

Maldita, and EFE Verifica

on their WhatsApp channels during the analysed period

Source: Own elaboration.

EFE Verifica has 7,952 followers[4] and does not present any biography on its profile. Its publication frequency is very irregular, and it has only shared content on 12 out of the 60 analysed days (Figure 1). Two types of messages are published on the channel. The first type consists of a headline followed by the statement «What do we verify?» and a «Conclusion», accompanied by a link to obtain all the information. The second type consists of a headline and a brief description along with the link to the web content.

4.2. Topics and functions of the messages shared

by the fact-checking agencies on their WhatsApp channels

If we analyse the topics covered by the messages published by the three fact-checking agencies, we observe that, in general, the predominant topics are related to international conflicts (19 %), the realm of politics in general (13.6 %), and topics related to science and technology (11.6 %) (Table 2).

These are three topics that have dominated the media agenda during the months analysed. The first one is linked to the conflict between Israel and Palestine, which, despite being a longstanding issue since 1948, gained momentum on October 7, 2023, following the Hamas attack. The second is marked by a moment of great political interest, such as the inauguration of Pedro Sánchez as the Prime Minister, held on November 15 and 16, 2023, and the negotiations to secure the necessary support for its approval. Finally, the third refers particularly to topics related to artificial intelligence or climate change, two highly relevant topics due to their political and social implications.

Table 2. Topics of the messages shared by the fact-checking agencies on their WhatsApp channels (%)

|

Topic |

Newtral |

Maldita |

EFE Verifica |

Total |

|

Science and technology |

1.6 |

24.3 |

– |

11.6 |

|

Economy |

4.8 |

7.9 |

– |

5.8 |

|

Health |

1.6 |

1.7 |

– |

1.6 |

|

Politics |

17.7 |

11.3 |

– |

13.6 |

|

Environment |

4.8 |

7.8 |

10.5 |

6.6 |

|

Culture and Sport |

– |

0.9 |

– |

0.4 |

|

Immigration |

3.2 |

2.6 |

– |

2.7 |

|

Territorial Policy |

8.1 |

8.7 |

5.3 |

8.1 |

|

Food |

– |

9.6 |

– |

4.3 |

|

International conflicts |

29.0 |

4.3 |

42.1 |

19 |

|

Terrorism |

5.6 |

0.9 |

5.3 |

3.5 |

|

Disinformation |

4.0 |

6.1 |

21.1 |

6.2 |

|

Security |

8.9 |

2.6 |

– |

5.4 |

|

Religion |

2.4 |

– |

– |

1.2 |

|

International politics |

4.0 |

3.5 |

– |

3.5 |

|

Social Policies |

2.4 |

3.4 |

– |

2.8 |

|

Incidents |

– |

0.9 |

15.8 |

1.6 |

|

Monarchy |

0.8 |

0.9 |

– |

0.5 |

|

Others |

0.8 |

2.6 |

– |

1.6 |

|

TOTAL |

99.7 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Source: Own elaboration.

If we analyse the data based on each of the WhatsApp channels, interesting differences among them can be observed. Newtral focuses primarily on two topics: international conflicts (29 %) and politics (17.7 %). As mentioned earlier, the conflict between Israel and Palestine and Pedro Sánchez's investiture have been abundant sources of misinformation, especially the former. Additionally, it also shares content related to territorial politics (8.1 %) and security (8.9 %). In the case of territorial politics, the agency debunks information related to the Amnesty Law and concessions made by Pedro Sánchez's government to Catalan politicians, especially concerning financing. Regarding security, the verifications revolve around scams that emerge in the online environment and topics related to cybersecurity.

In contrast, Maldita covers a wider range of topics, although those related to science and technology stand out (24.3 %). In this regard, a significant number of messages refer to Artificial Intelligence, such as the use of AI software to impersonate identities or predict the winning numbers in the Christmas lottery, or more technological matters such as the advantages or disadvantages of using public Wi-Fi networks. Maldita uses a colour code based on the legend of content used on its website so that users can clearly identify the topic. For instance, science-related posts have a green header, while technology-related ones have a blue header.

Maldita also stands out for the significant volume of content published on nutrition (9.6 %). In these posts, the fact-checking agency provides practical information on how to cook certain foods for freezing or on the properties of some foods beyond their energy consumption, among other topics. This type of publication sets it apart from Newtral and EFE Verifica, which do not share content on this topic.

Finally, EFE Verifica has the most concentrated thematic agenda. Apart from verifying information on international conflicts (42.1 %), it places special emphasis on topics related to misinformation in general (21.1 %), such as the agreement in which it participates with Microsoft for detecting misinformation in Latin America. Another frequent theme is events (15.8 %). Specifically, it published several pieces of information about the death of the Córdoba CF football player Álvaro Prieto.

Regardless of the topics of the content published by the three fact-checking agencies on their WhatsApp channels, we observe that, overall, 80.2 % of the messages do not identify any of the sources consulted. These percentages vary depending on the agency. Thus, Newtral does not include any reference to sources in 82.3 % of the publications, Maldita in 76.5 %, and EFE Verifica in 89.5 %.

Table 3. Typology of sources present

in the messages shared by

the fact-checking agencies on their WhatsApp channels (%)

|

Typology of sources |

Newtral |

Maldita |

EFE Verifica |

Total |

|

Official |

81.9 |

77.8 |

100 |

80.5 |

|

Professional |

13.6 |

3.7 |

– |

7.8 |

|

Alternative |

4.5 |

11.1 |

– |

7.8 |

|

Others |

– |

7.4 |

– |

3.9 |

|

TOTAL |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Source: Own elaboration.

With regard to the messages that do refer to a source, those of an official nature stand out particularly (Table 3). That is, those linked to public bodies or institutions whose authority is socially recognized and, as a result, are highly relevant. In the case of Newtral, the percentage of sources of a professional nature (13.6 %) is also noteworthy, mainly referring to the press or communication offices of private entities. On the other hand, Maldita gives great importance to alternative sources (11.1 %) and identifies experts in the field to refute or justify the arguments used in their publications.

Regarding the function of the messages shared by the three fact-checking agencies on their WhatsApp channels, we observe some interesting differences. While the content of Newtral (78.2 %) and EFE Verifica (84.2 %) is mainly dedicated to debunking false information, Maldita focuses on informing (65.2 %) readers about topics it considers relevant, serving a dual function: debunking false information and providing knowledge on these topics so that users can form an opinion and not believe the false content circulating on the internet (Table 4). It is also noteworthy that a high percentage of Maldita (7.8 %) and EFE Verifica (15.8 %) publications aim to advise readers on how to learn to detect false or manipulated information (Table 4).

Table 4. Function of the messages

shared by the fact-checking agencies

on their WhatsApp channels (%)

|

Function |

Newtral |

Maldita |

EFE Verifica |

Total |

|

Disclaimer |

78.2 |

27.0 |

84.2 |

55.8 |

|

Inform |

19.4 |

65.2 |

– |

38.4 |

|

Advise |

2.4 |

7.8 |

15.8 |

5.8 |

|

TOTAL |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Source: Own elaboration.

If we analyse those contents whose objective is to debunk, we observe that, in general terms, three types of false information stand out (Table 5). The first is the decontextualization of facts, statements, or images (26.7 %). This involves information that is real but is linked to a deliberately false or distorted context. The second is the reuse of images or videos (22.6 %) that are real but have been produced at another time or in a different context than the one they are intended to be linked to. And the third refers to deception through fabricated content (20.5 %). In other words, these are contents that have no connection to reality and are created to make the public believe false statements or events.

Table 5. Type of disinformation verified by fact-checking agencies on their WhatsApp channels (%)

|

Type of disinformation |

Newtral |

Maldita |

EFE Verifica |

Total |

|

Joke, satire or parody |

2.1 |

– |

6.3 |

2.1 |

|

Exaggeration |

9.3 |

19.4 |

25 |

13 |

|

Decontextualization |

28.9 |

12.9 |

43.8 |

26.7 |

|

Fabricated Content |

18.6 |

35.5 |

6.3 |

20.5 |

|

Manipulation of images |

12.4 |

19.4 |

– |

13 |

|

Reuse of images or videos |

25.8 |

12.9 |

18.8 |

22.6 |

|

Others |

3.1 |

– |

– |

2.1 |

|

TOTAL |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Source: Own elaboration.

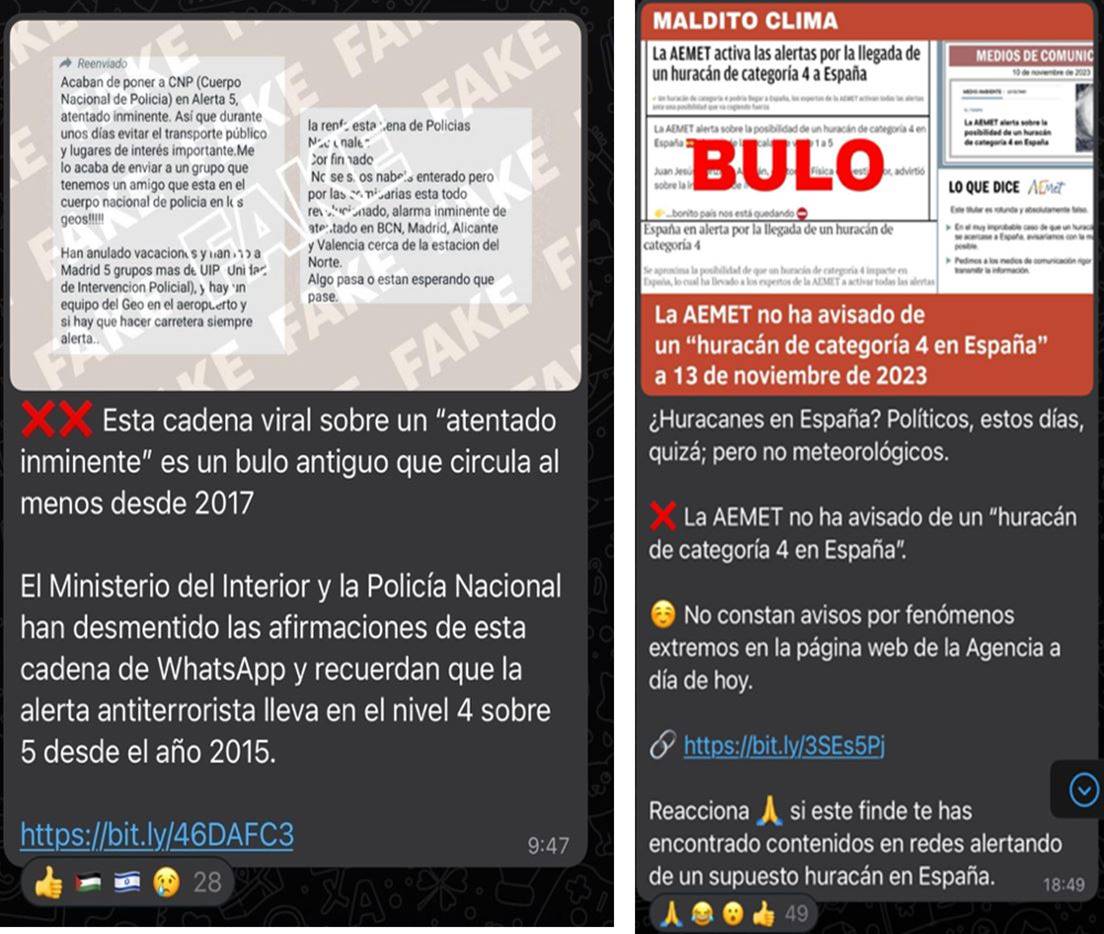

As for Newtral, a significant portion of its debunked content focuses on decontextualization (28.9 %) and the reuse of multimedia content (25.8 %) (Table 5). In the first case, we can find, for example, content related to old hoaxes that resurface through social media, such as an imminent terrorist attack or protests that have taken place in a specific location but are deliberately misrepresented (Figure 2). In the second case, we encounter images or videos that are real but are linked to events different from those initially portrayed. EFE Verifica follows similar patterns.

Figure 2. Examples of content

debunked by Newtral and Maldita

on their WhatsApp channels

Source: WhatsApp Channels of Newtral and Maldita

In the case of Maldita, over a third of the debunked content refers to fabricated content (35.5 %) and therefore false and created ad hoc to deceive the public (Table 5). Along these lines, the fact-checking agency has debunked various hoaxes related to immigrants arriving in Spain and the assistance they receive, or false alerts like the one from AEMET indicating that a Category 4 hurricane was going to hit Spain (Figure 2).

4.3. Interaction and multimedia presence in the WhatsApp channel of fact-checking agencies

Among the various potentials afforded by social media, the ability to interact with other users (Van Dijck, 2013) stands out, as well as the capacity to share multimedia elements to accompany or complement text. However, the nature of WhatsApp channels is based on a unidirectional communicative logic, as users cannot send or respond to messages shared by the channel owner. The only way the audience can interact with the content within these channels is by using reactions.

Regarding interaction, it is only predominantly present in Maldita, which has sought user feedback in 83.5 % of shared messages. The same cannot be said for Newtral and EFE Verifica, which either encourage it very little or not at all (3.2 % and 0 %, respectively).

Analysing the type of interaction promoted, in the case of Newtral, the phone number is shared, and users are encouraged to send in any information that generates doubts, and they want to verify. Conversely, Maldita seeks user reactions (78.8 %) to their content using emojis, either in a generic manner or by prompting them to use a specific one. In this regard, Maldita's messages have a relatively high average number of reactions (M = 73.96; SD = 63.026), reaching even up to 420 reactions in one message, compared to Newtral (M = 15.39; SD = 7.865) or EFE Verifica (M = 10.68; SD = 4.308).

In 11.5 % of cases, Maldita encourages users to share content with other users or groups, and in 9.6 % of posts, a phone number is provided where content can be sent for verification.

Regarding the use of multimedia elements, the data shows that all messages published by Newtral, Maldita, and EFE Verifica include at least one image or video and a link. At this point, it should be noted that, in Newtral, although the text refers to a video, only a screenshot of it appears in the message. This is not the case in Maldita's WhatsApp channel, where videos are indeed shared.

In over 95 % of instances, the links shared redirect users to the same content published on their websites, thus offering readers the opportunity to expand on the information if they are interested. In the remaining instances, they either link to the phone number available for users to share the information they wish to verify or their profiles on social media.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

The establishment of WhatsApp channels by Meta has introduced a new potentiality to the realm of communication. Its rollout in Spain in mid-September 2023 has prompted media outlets and news verification agencies to integrate yet another tool into their content dissemination strategies.

The analysis conducted in this research has allowed us to delve into the phenomenon of newly launched WhatsApp channels by studying their usage among Spanish verification agencies. In this regard, some interesting conclusions can be drawn.

Firstly, the data demonstrates that not all agencies attribute the same level of importance to WhatsApp channels during the period studied in this research. Thus, significant disparities exist between, on one hand, Newtral and Maldita, and on the other hand, EFE Verifica. This is evidenced by differences in the number of shared messages and the consistency of their publication. Additionally, we observe how Maldita adopts a content organization strategy aligned with its usage on its website, while the other two verifiers have less defined and aligned strategies with the rest of the platforms they employ for information dissemination. This could be attributed, especially, to verification agencies still adapting their content dissemination strategies to this new channel, indicating they are still searching for the formula that works best for them and helps them connect with the audience. Nonetheless, as seen on other social media platforms, independent fact-checkers more frequently utilize their own profiles on digital platforms compared to verification agencies associated with a media outlet, such as EFE Verifica, which have their own channels belonging to the parent medium (Dafonte-Gómez, Míguez-González, & Ramahí-García, 2022; Moreno-Gil & Salgado-de Dios, 2023).

Secondly, regarding the thematic focus of the messages (objective 1), our data demonstrates that, in general, they were influenced by current events. Thus, a significant portion of the content published by Newtral, Maldita, and EFE Verifica revolves around topics related to the Israel-Palestine conflict and significant political events like government negotiations and Pedro Sánchez's inauguration as president. Beyond these topics, Maldita's channel stands out, devoting a substantial portion of its messages to addressing topics related to nutrition, science, technology, and territorial politics such as the Amnesty Law. Similarly, EFE Verifica's messages also focus on topics related to events, misinformation in general, and the environment. Therefore, it represents a differentiation strategy by these verification agencies. These findings align with the strategy employed by fact-checkers on social media platforms like TikTok, where the most popular topics are those related to health, climate, and technology (Sidorenko-Bautista, Alonso-López, & Giacomelli, 2021).

Thirdly, our data indicates that the use of sources in the messages shared by verification agencies on their WhatsApp channels is not prioritized (objective 2). Thus, only 20 % of the messages, depending on the verification agency, make some reference to the sources consulted. When they do, they mostly opt for official sources due to their social acceptance and consequent reliability for the public. Maldita stands out in consulting a significant number of experts. This data may be linked to the topics addressed by each of the agencies, as content related to aspects such as science and technology or nutrition, for example, lends itself to using this type of sources.

Regarding functions (objective 3), verification agencies generally prioritize debunking false content. This is an expected outcome due to the inherent nature of verification agencies, whose main objective is primarily this (Graves & Cherubini, 2016; Guallar et al., 2020). However, Maldita stands out again, as it also seeks to inform users. In this sense, we observe how Maldita aims to educate its readers and, besides debunking false information which is circulating through various platforms, it also informs about topics that could potentially generate this type of content.

In fifth place, we detect that the use of data, facts, or contextualized multimedia resources, the creation of ad hoc false content, and the reuse of images or videos are the most frequently debunked forms of misinformation by the three verification agencies (objective 4). These are recognized as the most common forms of misinformation in the literature (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017).

Finally, our data demonstrates how all three verification agencies make appropriate use of digital language, incorporating various multimedia resources in all their publications (objective 5). However, concerning interaction, we observe that only Maldita seeks closeness with users, as well as their feedback, primarily in the form of reactions. This is a dynamic that has also been observed on platforms like TikTok, where fact-checkers do not interact with the audience despite being a necessary practice (Elizabeth & Mantzarlis, 2016). In this regard, we can establish that Maldita is the Spanish verification agency that makes the most of the inherent characteristics of WhatsApp channels.

Despite being exploratory in nature, the findings obtained in this research contribute to improving knowledge of the use of WhatsApp channels, a platform that is increasingly endowed with more potentialities, such as the recent possibility of incorporating surveys.

References

Arce-García, S.; Said-Hung, E. & Mottareale-Calvanese, D. (2022). Astroturfing as a strategy for manipulating public opinion on Twitter during the pandemic in Spain. Profesional de la Información, 35(3), e310310. doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.may.10

Bachmann, I. & Valenzuela, S. (2023). Studying the Downstream Effects of Fact-Checking on Social Media: Experiments on Correction Formats, Belief Accuracy, and Media Trust. Social Media + Society, 9(2). doi.org/10.1177/20563051231179694

Bardin, L. (1996). Análisis de contenido. Akal.

Bennet, W. & Livinstong, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122-139. doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317

Blanco, A. (2019). Posverdad. La nueva guerra contra la verdad y cómo combatirla. Doxa Comunicación, (29), 289-318.

Brandtzaeg, P. B.; Følstad, A. & Chaparro-Domínguez,M. A. (2018). How journalists and social media users perceive online fact-checking and verification services. Journalism practice, 12(9), 1109-1129. doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2017.1363657

Bloch, M. (1999). Historia e historiadores. Akal.

Buchanan, T. (2020). Why do people spread false information online? The effects of message and viewer characteristics on self-reported likelihood of sharing social media disinformation. PLoS ONE, 15. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239666

Burnam, T. (1975). The Dictionary of Misinformation. Thomas Y. Crowell.

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2024, 4 de febrero). 2024: un año de elecciones y...desinformación. Periódico Mediterráneo. Consultado el 5 de febrero de 2024. http://tinyurl.com/mscavp5z

Casero-Ripollés, A.; Doménech-Fabregat, H. & Alonso-Muñoz, L. (2023). Percepciones de la ciudadanía española ante la desinformación en tiempos de la COVID-19. Revista ICONO 14. Revista Científica de Comunicación y Tecnologías Emergentes, 21(1). doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v21i1.1988

Chan, J. (2022). Online astroturfing: a problem beyond disinformation. Philosophy & social criticism, Online first. doi.org/10.1177/01914537221108467

Comisión Europea (2019). Tackling online disinformation. Consultado el 4 de febrero de 2024. http://tinyurl.com/npbrsn23

Dafonte-Gómez, A.; Míguez-González, M. I. & Ramahí-García, D. (2022). Fact-checkers on social networks: analysis of their presence and content distribution channels. Communication & Society, 35(3), 73-89. doi.org/10.15581/003.35.3.73-89

Doob, L. W. (1950). Goebbels’ principles of propaganda. Public opinion quarterly, 14(3), 419-442. doi.org/10.1086/266211

Ecker, U. K. H.; Lewandowsky, S.; Cook, J.; Schmid, P.; Fazio, L. K.; Brashier, N.; Kendeou, P.; Vraga, E. K. & Amazeen, M. A. (2022). The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1, 13-29. doi.org/10.1038/s44159-021-00006-y

Elizabeth, J. & Mantzarlis. A. (2016). The fact is, fact-checking can be better. American Press Institute. http://tinyurl.com/4cu5xca6

Fernández-Castrillo, C. & Magallón-Rosa, R. (2023). El periodismo especializado ante el obstruccionismo climático. El caso de Maldito Clima. Revista Mediterránea De Comunicación, 14(2), 35-52. doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM.24101

Graves, L. & Cherubini, F. (2016). The rise of fact-checking sites in Europe. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford.

Guallar, J.; Codina, L.; Freixa, P. & Pérez-Montoro, M. (2020). Desinformación, bulos, curación y verificación. Revisión de estudios en Iberoamérica 2017-2020. Telos: revista de Estudios Interdisciplinarios en Ciencias Sociales, 22(3), 595-613.

Hayes A. & Krippendorff, K. (2007). Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures, 1(1), 77-89. doi.org/10.1080/19312450709336664

Huang, Y. & Wang, W. (2022). When a story contradicts: Correcting health misinformation on social media through different message formats and mechanisms. Information, Communication & Society, 25(8), 1192-1209. doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1851390

Humprecht, E. (2020). How Do They Debunk “Fake News”? A Cross-National Comparison of Transparency in Fact Checks. Digital Journalism, 8(3), 310-327. doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1691031

Lasswell, H. D. (1951). The strategy of Soviet propaganda. Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science, 4(2), 66-78. doi.org/10.2307/1173235

León, B.; Martínez-Costa, M. P.; Salaverría, R. & López-Goñi, I. (2022). Health and science-re-lated disinformation on Covid-19: a content analysis of hoaxes identified by fact-checkers in Spain. PLoS ONE, 17 (4), e0265995. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265995

López-Pan, F. & Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J. M. (2020). El fact checking en España. Plataformas, prácticas y rasgos distintivos. Estudios sobre el mensaje periodístico, 26 (3), 1045-1065. doi.org/10.5209/ESMP.65246

Margolin, D. B., Hannak, A. & Weber, I. (2018). Political Fact-Checking on Twitter: When Do Corrections Have an Effect? Political Communication, 35(2), 196-219. doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1334018

Moreno-Gil, V. & Salgado-de Dios, F. (2023). El cumplimiento del código de principios de la International Fact-Checking Network en las plataformas de verificación españolas. Un análisis cualitativo. Revista de Comunicación, 2(1), 293-307. doi.org/10.26441/RC22.1-2023-2971

Nyhan, B. & Reifler, J. (2015). The Effect of Fact-Checking on Elites: A Field Experiment on U.S. State Legislators. American Journal of Political Science, 59 (3), 628-640. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24583087

Organización Mundial De La Salud (2020). Gestión de la infodemia sobre la COVID-19: Promover comportamientos saludables y mitigar los daños derivados de la información incorrecta y falsa. http://tinyurl.com/yryf32sw

Palau-Sampió, D. (2018). Fact-checking and scrutiny of power: Supervision of public discourses in new media platforms from Latin America. Communication & Society, 31(3), 347-363. doi.org/10.15581/003.31.3.347-363

Sádaba,

C. & Salaverría, R. (2023). Combatir la desinformación con

alfabetización mediática: análisis de las tendencias en la Unión Europea. Revista

Latina de Comunicación Social, 81, 17-3.

doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2023-1552

Salaverría, R. & Cardoso, G. (2023). Future of disinformation studies: emerging research fields. Profesional de la Información, 32(5), e320525. doi.org/10.3145/epi.2023.sep.25

Salaverría, R.; Buslón, N.; López-Pan, F.; León, B.; López-Goñi, I. & Erviti, M. C. (2020). Desinformación en tiempos de pandemia: tipología de los bulos sobre la Covid-19. Profesional de la Información, 29(3), e290315. doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.may.15

Sidorenko-Bautista, P.; Alonso-López, N. & Giacomelli, F. (2021). Espacios de verificación en TikTok. Comunicación y formas narrativas para combatir la desinformación. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 79, 87-113. doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2021-1522

Stencel, M. ; Ryan, E. & Luther, J. (2022). Fact-checkers extend their global reach with 391 outlets, but growth has slowed. Poynter. Consultado el 5 de febrero de 2024. http://tinyurl.com/53ka6e8k

Terol-Bolinches, R. & Alonso-López, N. (2020). La prensa española en la Era de la Posverdad: el compromiso de la verificación de datos para combatir las Fake News. Revista Prisma Social, (31), 304-327.

Ufarte-Ruiz, M. J.; Anzera, G. & Murcia-Verdú, F. J. (2020). Plataformas independientes de fact-checking en España e Italia: Características, organización y método. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 11(2), 23-39. doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2020.11.2.3

UTECA (2022). I Estudio sobre la desinformación en España. Universidad de Navarra. http://tinyurl.com/2bfbbjvf

Van-Dijck, J. (2013). The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. Oxford University Press.

Vázquez-Herrero, J.; Vizoso, Á. & López-García, X. (2019). Innovación tecnológica y comunicativa para combatir la desinformación: 135 experiencias para un cambio de rumbo. Profesional de la Información, 28(3). doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.may.01

Wardle, C. & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information disorder: toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy-making. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Walter, N.; Cohen, J.; Holbert, R. L. & Morag, Y. (2020). Fact-Checking: A Meta-Analysis of What Works and for Whom. Political Communication, 37(3), 350-375. doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1668894

Zunino, E. (2021). Medios digitales y COVID-19: sobreinformación, polarización y desinformación. Universitas, 34, 133-154.

[1] Model based on Wardle and Derakhshan (2017).

2 Number of followers as of January 23, 2024.

3 Number of followers as of January 23, 2024.

4 Number of followers as of January 23, 2024.