index●comunicación | nº 14(2)

2024 | Pages 109-135

E-ISSN: 2174-1859 | ISSN: 2444-3239 | Legal Deposit: M-19965-2015

Received 13_03_2024 | Accepted 15_06_2024 | Published 15_07_2024

DISINFORMATION AND MEDIA TRUST IN THE SOUTH OF EUROPE. A MODERATED MEDIATION MODEL

DESINFORMACIÓN Y CONFIANZA EN LOS MEDIOS EN EL SUR DE EUROPA. UN MODELO DE MEDIACIÓN MODERADA

https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/14/02Desinf

Aurken Sierra Iso

University of Navarra

aurken@unav.es

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1749-7888

María Fernanda Novoa-Jaso

University of Navarra

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1858-8343

Javier Serrano-Puche

University of Navarra

jserrano@unav.es

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6633-5303

Línea de financiación: Este artículo es resultado del proyecto «DigiNativeMedia II – Medios Nativos Digitales en España: tipologías, estrategias, competencias y sostenibilidad periodísticas (2022-2025)» PID2021-122534OB-C22, financiado por Agencia Estatal de Investigación, Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades de España y Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional

![]() To quote this

work: Sierra Iso, A., Novoa-Jaso, M. y Serrano-Puche, J. (2024). Disinformation

and Media Trust in the South of Europe. A Moderated Mediation Model. index.comunicación,

14(2), 109-135. https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/14/02Desinf

To quote this

work: Sierra Iso, A., Novoa-Jaso, M. y Serrano-Puche, J. (2024). Disinformation

and Media Trust in the South of Europe. A Moderated Mediation Model. index.comunicación,

14(2), 109-135. https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/14/02Desinf

Abstract: Our study explores how the type of news source acts as an intermediary in the connection between people's concerns about disinformation and their overall trust in the media. Additionally, we examine how a person's ideology influences their choice of news sources and, ultimately, their trust in news in general. To do so, we examine data from the Digital News Report 2022 (N= 10,106) for five news markets: France (N= 2059), Greece (N= 2004), Italy (N= 2004), Portugal (N= 2011), and Spain (N= 2028). The results confirm that ideology plays a moderating role in the relationships between «disinformation concern», «trust in media», and «type of media source». Increased concern about disinformation significantly decreases trust in the news. Individuals who are concerned about disinformation have higher consumption of traditional media (press, radio, and television). This research presents a moderated model that explains how these various factors interact to shape media trust.

Keywords: Disinformation; Trust, News; Legacy Media; Digital Media; Mediated moderation model.

Resumen: Nuestro estudio explora cómo el tipo de fuente de noticias actúa como factor mediador en la relación entre la preocupación de las personas por la desinformación y su confianza general en los medios de comunicación. Además, examinamos cómo la ideología de una persona influye en su elección de fuentes de noticias y, en última instancia, en su confianza en las noticias en general. Para ello, examinamos los datos del Digital News Report 2022 (N= 10.106) para cinco mercados de noticias: Francia (N= 2059), Grecia (N= 2004), Italia (N= 2004), Portugal (N= 2011) y España (N= 2028). Los resultados confirman que la ideología desempeña un papel moderador en las relaciones entre «preocupación por la desinformación», «confianza en los medios» y «tipo de fuente mediática» Una mayor preocupación por la desinformación disminuye significativamente la confianza en las noticias. Además, los individuos altamente preocupados por la desinformación tienden a aumentar su consumo de medios de comunicación tradicionales. Esta investigación presenta un modelo moderado que explica cómo interactúan estos diversos factores para conformar la confianza en los medios de comunicación.

Palabras clave: desinformación; confianza; noticias; medios tradicionales; medios digitales; modelo de mediación moderada.

1. Introduction

Trust is a crucial element in maintaining social cohesion among members of a society (Hawley, 2012). It extends beyond interpersonal interactions to include goods, services, and institutions, and its formation is influenced by both the expectations of the sender and the behaviour of the receiver (Eisenstadt & Roniger, 1984).

Regarding the media, trust is a fundamental component that shapes the bond between citizens and the media (Fawzi et al., 2021). In recent decades, it has been a central theme in academic research, generating an abundant literature (Kohring & Matthes, 2007; Meyer, 1988; Stamm & Dube, 1994; Strömbäck et al., 2020). This research is related to credibility studies, a concept with a long history in communication (Hovland & Weiss, 1951), and closely linked to trust. Despite the abundance of research, there is no agreement on the definition of trust, its level of operation, or how to measure it (Prochazka & Schweiger, 2019). The lack of precision in both concept and methodology is exacerbated by the overuse of one-dimensional quantitative techniques, resulting in an incomplete understanding of this phenomenon (Garusi & Splendore, 2023).

Nevertheless, at the broadest conceptual level, there is significant consensus that news media trust refers to the relationship between citizens (the trustors) and the news media (the trustees) where citizens, however tacit or habitual, in situations of uncertainty expect that interactions with the news media will lead to gains rather than losses (Strömbäck et al., 2020:142).

The significance of trust in news, both academically and professionally, is due to its influence on people's relationship with news (Moran & Nechushtai, 2022), which in turn affects their news consumption (Fletcher & Park, 2017; Schranz et al., 2018).

Taking these factors into consideration, our study is dedicated to probing the determinants of trust in news, with a particular emphasis on the impact of disinformation concern on shaping news consumption patterns. To do so, we used a quantitative methodology based on the Digital News Report survey (Newman et al., 2023) and statistical analysis (Hayes, 2022). Specifically, we delve into the mediation role played by the type of news source in the relationship between disinformation concern and media trust. Moreover, we scrutinize how ideology moderates the link between individuals' selection of media sources and their overarching trust in news. This research culminates in a model of moderated mediation elucidating how these diverse influences shape media trust.

Media credibility and trustworthiness hinge on a range of factors, including the accuracy of information dissemination, impartiality, independence from external actors, and a commitment to upholding audience interests (Lee, 2010). These elements play a crucial role in establishing media outlets as reliable sources of information and fostering public trust. Although there is no universal definition of trust in news media, in this research we conceptualize it as «the individual’s willingness to be vulnerable to media objects, based on the expectation that they will perform a) satisfactorily for the individual and/or b) according to the dominant norms and values in society (i.e. democratic media functions)» (Fawzi et al., 2021, p. 156). Therefore, it is established through a cognitive and relational process in which individuals evaluate the qualities of an information source, the content of its messages, or the media system as a whole (Lucassen & Schraagen, 2012; Medina et al., 2023; Strömbäck et al., 2020). The asset being referred to is fragile and intangible, and is highly relational in nature. It is sensitive to social, economic, cultural, and technological changes (Serrano-Puche et al., 2023). Therefore, it is important to consider the political and cultural

context in which this relationship develops, as well as the expectations that citizens have towards media institutions. These factors can influence their perceptions and attitudes towards media institutions (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2019; Tsfati & Ariely, 2014).

Criticism of the media has intensified in most Western democracies in recent years from various quarters. Changes in the levels of credibility and trust inspired by journalistic activity can be observed in many countries (Hanitzsch et al., 2018). For instance, trust indices in traditional media have shown a negative trend in Spain in recent years (Serrano-Puche, 2017; Vara-Miguel, 2018; Vara-Miguel et al., 2022). According to Edelman (2023), only 38% of the population considers the media to be a trustworthy institution. The Digital News Report (Amoedo et al., 2023) reports a slightly lower percentage of 33%. This media skepticism among citizens is fuelled by the perception that the media does not meet professional standards, such as incomplete coverage, lack of fairness, or inaccuracies. Additionally, the belief that journalists would sacrifice accuracy for personal or commercial gain contributes to this skepticism (Tsfati & Cappella, 2003). Skepticism towards the media can stem from a constructive view, associated with citizens' legitimate expectations of fulfilling a social function (Quiring et al., 2019). However, it can also result in cynicism, which is associated with populist or anti-establishment attitudes (Markov & Min, 2023; Tsfati & Cohen, 2005).

The lack of trust is a global and systemic phenomenon that affects a wide range of institutions, including multinational companies, political parties, NGOs, religious institutions, and corporations from various sectors (Edelman, 2023; Pérez-Latre, 2022). In essence, there is a widespread lack of trust in conventional institutions, which seem unable to offer solutions to social, economic, environmental, or public health issues (Perry, 2021; Pew Research Center, 2022; Sapienza, 2021).

Returning to the media, the transformation experienced in the communication ecosystem due to the irruption of digital platforms and technologies implies a challenge for traditional media. This new ecosystem is characterized by the hybridization of classic and digital media logics (Chadwick, 2013), the blurring of traditional boundaries of journalism (Carlson & Lewis, 2015), and the ability of citizens to choose sources and content (Van-Aelst et al., 2017). This leads to competition among different agents to capture the time and attention of users (Webster, 2014).

2.2. Disinformation and media trust

The phenomenon of disinformation has garnered significant attention in recent years, drawing scrutiny from both academics and the public. This focus has yielded a deeper understanding of the concept itself, along with its causes and consequences (Ha et al., 2019; High Level Expert Group on Fake News and Disinformation [HLEG], 2018). This attention is nourished by concern for the threat it poses to democratic institutions (Miller & Vaccari, 2020), as well as by the realization that it is an increasingly complex phenomenon due to the diversity of actors involved and the modes of dissemination with which it emerges. In this sense, and following Wardle and Derakhshan (2017, p. 20), it is important to conceptually distinguish «Information that is false and deliberately created to harm a person, social group, organization or country» (disinformation) from «Information that is false, but not created with the intention of causing harm» (misinformation).

In any case, the rise of all this «problematic information» (Jack, 2017) also poses a challenge to the media, as it increases citizens' uncertainty about the reliability of content circulating in the public sphere, which can lead to less trust in the media (Vaccari & Chadwick, 2020). Hameleers, Brosius, and De-Vreese (2022) concluded, based on a survey in 10 European countries, that users with stronger perceptions of disinformation are more likely to consume news in social networks and alternative non-mainstream media. Additionally, research by Zimmermann and Kohring (2020) shows that those who trust the media less are more likely to believe online disinformation. Conversely, citizens in countries with high levels of media trust and low levels of polarization and populist communication are more resilient to disinformation (Humprecht et al., 2020). Ultimately, structural tensions in the media environment are related to the breakdown of trust in democratic institutions, which paves the way for disinformation as a disruptive element in the public sphere, as recent history has shown (Magallón-Rosa, 2022).

The perception that news stories contain false information can lead to distrust of the media. We therefore propose the following hypothesis:

- H1: People who are more concerned about disinformation tend to trust the media less.

The rise of the new hybrid media system, in which digital and new media outlets have challenged the dominance of traditional media, has affected the level of trust that individuals have in the media (Chadwick, 2013; Fawzi et al. 2021). The availability of a greater number of news sources has enabled citizens to question the accuracy of news outlets with which they disagree (Strömbäck et al., 2020). Today, individuals have access to a wider range of media sources, enabling them to choose from a greater variety of stories. Some sources may offer stories that align with their existing beliefs, which can be perceived as more reliable (Hameleers et al., 2022).

When citizens distrust the mainstream media, they tend to withdraw from it and turn towards alternative sources (Müller & Schulz, 2021; Tsfati & Cappella, 2003). One reason for distrust of the news media and increased use of alternative outlets could be the perception that the information reported in the mainstream media is false or even deliberately misleading. Thus, perceptions of misinformation and disinformation are both associated with reduced trust in the news media. They are also associated with reduced consumption of traditional TV news, but not with reduced consumption of newspapers and (mainstream) online news (Ren et al., 2024). However, those with stronger perceptions of misinformation and disinformation are more likely to consume news from social media and alternative, non-mainstream outlets. This pattern is stronger for those with higher perceptions of disinformation (Hameleers et al., 2022).

Therefore, our second hypothesis would be:

H2: Individuals highly concerned about disinformation tend to increase their consumption of legacy media sources (traditional press, radio, or television).

Several studies have shown a correlation between an individual's preferred media source (traditional or online) and media trustworthiness (Strömbäck et al., 2020; Tsfati & Cappella, 2003; Tsfati & Cohen, 2005). This correlation is based on different communicative phenomena. Information overload and the fear of disinformation, as well as the overabundance of sources, make it easier for users to be more selective about the news sources they use (Holton & Chyi, 2012; Strömbäck et al., 2020). When choosing a media source, audiences tend to favour sources they trust over those they distrust when evaluating their value (Vara-Miguel, 2022). Therefore, one could assume that the relationship between users' disinformation concern and their experienced media trust could be somehow influenced by the type of media source they choose.

In order to examine the impact of users' choice of news source on the relationship between disinformation concern and media trust, we employed mediation analysis. This widely used method transcends the limitations of mere correlation, delving into the underlying mechanisms that drive relationships among certain variables. Its name comes from the fact that it examines how an independent variable influences a dependent variable through a mediator variable. Therefore, this approach helps identify whether the effect of one variable on another is direct or if there are other variables which influence the behaviour of the latter (Igartua & Hayes, 2021). Thus, moving beyond simple correlations and shedding light on these connections, this method can provide deeper insights into the nature of relationships and lead to more effective interventions. In our study, the mediation analysis allowed us to assess the mediating role of the type of news source in the association between disinformation concern and media trust. Specifically, we analysed whether the mediator variable M (type of news source) mediated the direct relationship between disinformation concern (our independent variable Y) and media trust (our dependent variable X). This approach allowed us to gain a comprehensive understanding of the causal connections among X, Y, and M.

H3: The effect of disinformation concern (X) on media trust (Y) will be mediated by the type of media source (M) chosen.

2.3. Disinformation, ideology and media trust

When examining the repercussions of disinformation, ideology emerges as a significant factor. This is chiefly due to ideological disparities. There exists a substantial body of literature indicating that individuals situated at the extremes of the ideological spectrum are more inclined towards disinformation, both because they favour it and because disinformation sources target them (Freelon et al., 2022). Studies suggest that extremist individuals embrace disinformation as it reinforces their extreme viewpoints, sparing them the discomfort of engaging with factual information that may challenge their political beliefs (Harper & Sykes, 2023). This phenomenon is logical, considering that the most radical voters are typically the most politically engaged and are more tolerant of biased information (Benkler et al., 2018).

Furthermore, ideology influences trust in the media, given that journalism is viewed as integral to the institutional framework of liberal democracies. Consequently, individuals' trust in the media is significantly shaped by their trust in political institutions. Hanitzsch et al. (2018) refer to this as the «trust nexus», a connection that tends to strengthen in politically polarized environments. Skepticism towards journalistic institutions and media platforms is often fuelled by anti-establishment sentiments (Hanitzsch et al., 2018), which also correlate with the consumption of disinformation and conspiracy theories (Uscinski et al., 2021). Scholarly research often cites partisan tribalism and ideological extremism as explanatory factors for this association. In several Western democracies, public polarization has increased, closely aligning with partisan and ideological identities, while animosity towards political opponents has intensified (Abramowitz & McCoy, 2019; Kalmoe & Mason, 2019). Meanwhile, political elites are becoming increasingly polarised and framing their appeals along partisan and ideological lines. This statement reinforces the importance of left-right identities in politics and highlights the relevance of ideology when analysing media trust (Levendusky, 2010).

Drawing from the hypothesis suggesting that disinformation will negatively affect trust in news, this effect will be more pronounced among individuals with more extreme political ideologies. Those positioned at the far ends of the ideological spectrum are inclined to embrace misinformation aligning with their existing beliefs, thereby diminishing their trust in news diverging from their worldview. Hence, we propose the following hypotheses to study the relationship between disinformation concern (X), media trust (Y), preferred media type (M) and ideology (W):

H4: The ideology (W) of the respondents will serve as a moderating variable in the association between disinformation concern (X) and media trust (Y).

H5: The ideology (W) of the respondents will serve as a moderating variable in the association between preferred type of media (M) and media trust (Y)

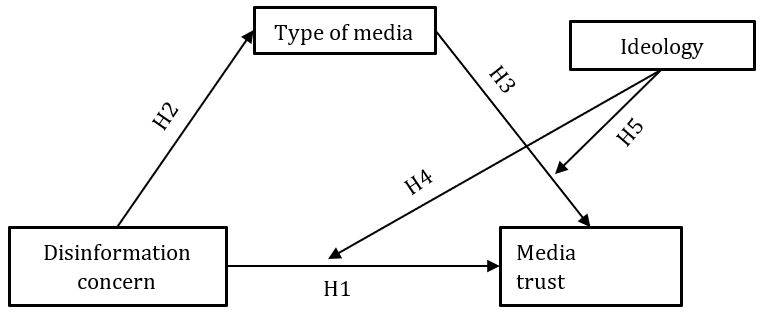

The depicted figure in Figure 1 illustrates the proposed connections within a causal framework among disinformation concern (X), media trust (Y), type of news source (M), and ideology (W). The model's paths (a, b, and c') represent the direct impacts of one variable on another. To calculate the indirect effect of X on Y, we multiplied paths a and b.

Figure 1. Model of moderated mediation. PROCESS Model 15

Source: Own elaboration based on Hayes (2022)

3. Methodology

In this section, we describe the data and methods used to test our hypotheses and answer the research questions on news trust in the media in five European countries: France, Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. We use data from the Digital News Report survey (Newman et al., 2023), a large-scale study focused on news consumption and attitudes toward news, conducted annually by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and fielded by YouGov. The selected countries belong to the Polarised Pluralist or Mediterranean model proposed by Hallin and Mancini (2004). This justifies the choice of the sample and guarantees a certain homogeneity. The total sample (N= 10106) integrates news consumption from five countries: France (N= 2059), Greece (N= 2004), Italy (N= 2004), Portugal (N= 2011), and Spain (N= 2028). Samples were collected from panels in various countries. Participants were asked to complete the survey while adhering to predefined quotas for age, gender, and region. The collected samples were then weighted according to census data to ensure alignment with the demographics of the national population. Conducted by YouGov on behalf of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, fieldwork was carried out via an online questionnaire from late January to early February 2022. The gathered data underwent weighting adjustments based on predetermined targets derived from census and industry-recognized data, including variables such as age, gender, region, newspaper readership, and social grade, to accurately mirror the demographics of each country's population. The sample consisted of adults (18+ years) with internet access, with over 2,000 respondents in each country (see Table 1). It is important to note that the data were collected from an online panel, and therefore respondents were not randomly sampled.

Table 1. Sample size and internet penetration (2022)

|

Country |

Sample Size |

Internet Penetration |

|

France |

2059 |

92.2% |

|

Greece |

2004 |

78.5% |

|

Italy |

2004 |

90.8% |

|

Portugal |

2011 |

88.1% |

|

Spain |

2028 |

93.0% |

Source: Internet World Stats

3.1. Dependent variable: media trust

The dependent variable in this study is «media trust». In the questionnaire, participants were asked the following question: «We are now going to ask you about trust in the news. First, we will ask you about how much you trust the news as a whole within your country. Then we will ask you about how much you trust the news that you choose to consume: «I think you can trust most news most of the time». The options comprised five response categories based on level of agreement: «strongly disagree», «tend to disagree», «neither agree nor disagree», «tend to agree» and «strongly agree». (Mean (M) = 3, Standard Deviation (SD) = 1,06).

The method used to assess media trust aligns with established methodologies from prior studies, such as the Digital News Report 2017 in Australia (Watkins et al., 2017), Edelman’s Global Trust Barometer (2018–2024), the Pew Research Center survey on modern news consumers (2016–2024), and the Reuters Institute Digital News Report (2012–2021). These studies employed a multi-point scale to measure participants' trust in the news media. Williams (2012) introduced the term 'media trust' as an analytical approach, distinguishing it from interpersonal and institutional trust, and linking it to audience engagement with various news outlets. Therefore, most trust frameworks in journalism studies consider media trust as a general sentiment rather than something specific to certain situations or individual outlets (Engelke et al., 2019). This methodology is widely accepted and enables comparisons of trust and distrust levels across different types of news media and countries.

3.2. Independent variables

3.2.1. Disinformation concern

In order to analyse disinformation concern, we used the following questions from the survey: «Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: Thinking about online news, I am concerned about what is real and what is fake on the internet». The options comprised five response categories based on level of agreement, codified from 1 to 5 as follows: «strongly disagree» (1), «tend to disagree» (2), «neither agree nor disagree» (3), «tend to agree» (4) and «strongly agree» (5). (M = 3.65, SD = 0.98).

3.2.2. Political alignment

This variable ranges from 1 to 7 and corresponds to the following survey question: «Some people talk about 'left', 'right' and 'centre' to describe parties and politicians. (Generally, socialist parties would be considered ‘left wing’ whilst conservative parties would be considered ‘right wing’). With this in mind, where would you place yourself on the following scale?»: «Very left-wing», «Fairly left-wing», «Slightly left-of-centre», «Centre», «Slightly right-of-centre», «Fairly right-wing», «Very right-wing» and «Don't know». (M = 4.64, SD = 2.21).

3.2.3. Type of source

To gauge the main outlet for news among respondents, we used the following question: «Which source of news would you say is your main source of news, considering the sources you used in the past week?». The respondents had 11 alternatives, which were recoded into four categories, ranging from 1 to 4 as follows: 1 (television news bulletins or programmes, 24-hour news television channels, radio news programmes and bulletins and printed newspapers and magazines), 2 (digital editions and websites of traditional news sources), 3 (digital-born outlets), and 4 (social media). (M = 1.95, SD = 1.19).

3.3. Control variables

The control variables of our research were age [which was recoded into six categories: 1 (18 to 24), 2 (25 to 34), 3 (35 to 44), 4 (45 to 54), 5 (55 to 64) and 6 (65 or above)], education level [which was also recoded to simplify the original ten educational alternatives into five categories: 1 (Primary school or less), 2 (completed Secondary school or Bac-A levels), 3 (completed professional qualification), 4 (completed bachelor’s degree), and 5 (postgraduate, be it master’s or doctoral degree)], gender [male (1) or female (2)], and household income [1 (less than 15,000 €/year), 2 (15,000-35,000 €/year), and 3 (more than 35,000 €/year)]. As Vara et al. (2023) state, these control variables have been consistently identified as the most important when addressing variance in media trust perceptions.

3.4. Data analysis

The statistical procedures involved in this study consisted of the following steps: first, we conducted a descriptive analysis of the variables we were analysing in the study, followed by a correlation analysis across the variables. Once this step was completed, we conducted a moderated mediation analysis using IBM SPSS macro PROCESS (Model 15; Hayes, 2015). The PROCESS macro is commonly used in the social sciences to analyse complex models that include both mediating and moderating variables, and remains the preferred tool for analysing advanced models that describe moderated mediation processes (Hayes, 2015). Using PROCESS, model coefficients can be estimated while also finding t- and p-values, standard errors and confidence intervals using OLS regressions. This allowed us to find direct and indirect effects of mediation among our chosen variables, which resulted in the proposed model of moderated mediation. In our case, inferences about conditional and indirect effects in the statistical analyses were made using percentile bootstrap confidence intervals (n = 10,000 samples; 95% lower and upper percentiles), which were found to be significantly different from zero and therefore relevant to our study (Hayes, 2018; Hayes and Scharkow, 2013).

Table 2: Frequencies (%). Control variables, pooled and by countries

|

Variable |

Categories |

POOLED |

|

FR |

IT |

SP |

PT |

GR |

|

|

N |

10106 |

|

2059 |

2004 |

2028 |

2011 |

2004 |

|

Gender |

Male |

48% |

|

48% |

46% |

48% |

47% |

50% |

|

Female |

52% |

|

52% |

54% |

52% |

53% |

50% |

|

|

Household Income |

Low |

27% |

|

34% |

20% |

27% |

20% |

31% |

|

Medium |

51% |

|

43% |

57% |

48% |

53% |

53% |

|

|

High |

23% |

|

23% |

23% |

25% |

27% |

16% |

|

|

Education |

Primary or less |

5% |

|

7% |

2% |

8% |

6% |

2% |

|

Secondary |

51% |

|

51% |

73% |

41% |

60% |

28% |

|

|

Prof. qualification |

13% |

|

18% |

6% |

19% |

6% |

17% |

|

|

Graduated. Bach. |

18% |

|

8% |

6% |

21% |

20% |

36% |

|

|

Postgraduate |

13% |

|

15% |

13% |

11% |

7% |

17% |

|

|

Age |

18-24 |

8% |

|

8% |

6% |

7% |

9% |

10% |

|

25-34 |

14% |

|

15% |

13% |

15% |

14% |

14% |

|

|

35-44 |

18% |

|

16% |

18% |

19% |

18% |

18% |

|

|

45-54 |

19% |

|

17% |

21% |

19% |

20% |

19% |

|

|

55-64 |

26% |

|

20% |

24% |

26% |

28% |

32% |

|

|

65+ |

15% |

|

24% |

19% |

14% |

10% |

8% |

Source: Own elaboration based on Reuters Institute Digital News Report survey (2023).

3.4.1. Descriptive statistics

The overall trend in four of the countries analysed shows a balance in the number of respondents claiming to trust most of the news versus those saying the contrary (35.4% v. 31.3% on average). Portugal stands out as a clear outlier in this question, with a vast majority of Portuguese respondents (61.5%) claiming to trust most news most of the time, which explains the wide difference in the mean level of trust in news across countries [F(4, 10101) = 165, p = <.001, η2 = .61]. The post-hoc analysis using Tukey’s USD test confirms this difference, showing that the mean level of trust in news was significantly higher in Portugal (M = 3.5, SD = 1) than in France (M = 2.8, SD = 1.04), Greece (M = 2.81, SD = 1), Italy (M = 3.04, SD = 0.97) and Spain (M = 2.86, SD = 1.11).

Table 3: Media trust. Frequencies, means and standard deviations.

|

|

POOLED |

FR |

IT |

SP |

PT |

GR |

|

Strongly disagree |

9,7 |

13 |

6,9 |

3,8 |

11,4 |

13,2 |

|

Tend to disagree |

22,4 |

24,9 |

21,3 |

15 |

25,3 |

25,6 |

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

30,6 |

33,3 |

35,4 |

19,7 |

36,9 |

27,5 |

|

Tend to agree |

32,7 |

26,5 |

33,4 |

50,7 |

24 |

29,3 |

|

Strongly agree |

4,6 |

2,4 |

2,9 |

10,8 |

2,4 |

4,3 |

|

Means |

3,00 |

2,80 |

3,04 |

3,50 |

2,81 |

2,86 |

|

SD |

1,06 |

1,04 |

0,97 |

1,00 |

1,00 |

1,11 |

Source: Own elaboration based on Reuters Institute Digital News Report survey (2023).

Table 4 presents data on main sources of news, ideology and disinformation concern for the five countries analysed in this study. Generally, media consumption shows a clear distinction in the media diet of respondents. On the one hand, France, Italy and Portugal show a similar pattern, with a clear dominance of traditional media. The distribution of news consumption across these three countries shows traditional news sources as the primary news sources (M = 59.57, SD = 2.55). On the other hand, Greece and Spain show a higher prevalence of social media (M = 40.5, SD = 8.2) and less reliance on traditional news sources. The ANOVA shows the mean level of main source for news vary from country to country [F(4, 9648) = 128.36, p = <.001, η2 = .51]. The post-hoc analysis using Tukey’s HSD test showed that the mean level of main source was significantly higher in Greece (M = 2.46, SD = 1.23) and Spain (M = 1.77, SD = 1.11), which shows consistent prevalence of social media over traditional sources in both markets than in France (M = 1.76, SD = 1.11), Italy (M = 1.77, SD = 1.11) and Portugal (M = 1.77, SD = 1.17).

Regarding ideology, significant differences can be found in the scores among the countries included in the analysis. Descriptive statistics revealed the following mean ideology scores for each country: France (M = 5.1646), Greece (M = 4.6816), Italy (M = 4.7854), Portugal (M = 4.5027), and Spain (M = 4.0641). An ANOVA test was conducted to determine if there were significant differences in ideology scores between the countries. The results indicated a significant difference among the countries (F(4, 10101) = 69.409, p < 0.001), suggesting that at least one country's ideology mean significantly differed from the others. Post-hoc comparisons using Tukey's HSD test revealed significant differences between the ideology scores of all pairs of countries (p < 0.05), except for the comparison between Italy and Greece (p = 0.559).

A one-way ANOVA was also conducted to determine the effect of nationality (France, Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain) on fear for disinformation among participants. The results indicate a significant effect, [F(4, 10101) = 85.75, p = <.001] η2 =.03]. Post-hoc analyses using Tuckey’s HSD test indicated that fear for disinformation was significantly higher in Portugal (M = 3.91, SD = 0.93) than in all other countries (p <.001). Fear for disinformation was also significantly higher in Spain (M = 3.78, SD = 1.07) than in France (M = 3.4, SD = 0.96), Italy (M = 3.55, SD = 0.92) and Greece (M = 3.6, SD = 0.92).

3.4.2. Correlation analysis

Table 4 shows the correlation analysis of the main variables. The analysis showed that all key variables had a statistically significant relationship with each other, although the sign varied. The correlation matrix revealed a significant positive relationship between type of news source and ideology (r = 0.043, p < 0.001). There were also negative relationships between type of news source and disinformation concern (r = 0.027, p = 0.009) and media trust (r = -0.183, p < 0.001). A negative sign indicates an inverse relationship between news source type and disinformation concern and media trust. In this case, this means that respondents whose main news source was non-digital (i.e., printed media, television or radio) showed higher levels of disinformation concern and lower levels of trust in the news overall.

Table 4: Frequencies (%). Independent variables. Pooled and by countries.

|

|

|

POOLED |

FR |

IT |

PT |

GR |

SP |

|

Main source |

Traditional news sources |

52 |

56.70 |

59.1 |

62.9 |

32.3 |

48.7 |

|

Digital edition traditional |

15.6 |

14.10 |

14.5 |

12.6 |

16.8 |

20 |

|

|

Digital-born outlets |

8.8 |

7.4 |

9.2 |

4.4 |

17.6 |

5.3 |

|

|

Social media |

19.2 |

13.6 |

13.9 |

17.8 |

29.4 |

21.3 |

|

|

Mean |

1.95 |

1.76 |

1.77 |

1.77 |

2.46 |

1.99 |

|

|

SD |

1.19 |

1.11 |

1.11 |

1.17 |

1.23 |

1.21 |

|

|

Ideology |

Very left-wing |

3.9 |

5.00 |

2.8 |

5.1 |

3.7 |

3.1 |

|

Fairly left-wing |

17.7 |

17.14 |

13 |

20.4 |

9.9 |

28.1 |

|

|

Slightly left-of-centre |

14.5 |

7.14 |

17.6 |

14.4 |

17.4 |

16.2 |

|

|

Centre |

16.6 |

12.04 |

14.3 |

16.5 |

24.9 |

15.6 |

|

|

Slightly right-of-centre |

12 |

6.95 |

16.7 |

10.4 |

14.5 |

11.5 |

|

|

Fairly right-wing |

11.5 |

15.69 |

13.5 |

9.3 |

7.4 |

11.3 |

|

|

Very right-wing |

4 |

9.57 |

2.2 |

3.5 |

2 |

2.8 |

|

|

Mean |

4.64 |

5.16 |

4.79 |

4.50 |

4.68 |

4.06 |

|

|

SD |

2.21 |

2.38 |

2.11 |

2.28 |

2.07 |

2.05 |

|

|

Disinformation

|

Strongly disagree |

9.7 |

13 |

6.9 |

3.8 |

11.4 |

13.2 |

|

Tend to disagree |

22.4 |

24.9 |

21.3 |

15 |

25.3 |

25.6 |

|

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

30.6 |

33.3 |

35.4 |

19.7 |

36.9 |

27.5 |

|

|

Tend to agree |

32.7 |

26.5 |

33.4 |

50.7 |

24 |

29.3 |

|

|

Strongly agree |

4.6 |

2.4 |

2.9 |

10.8 |

2.4 |

4.3 |

|

|

Mean |

3.00 |

2.80 |

3.04 |

3.50 |

2.81 |

2.86 |

|

|

SD |

1.06 |

1.04 |

0.97 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.11en |

Source: Own elaboration based on Reuters Institute Digital News Report survey (2023).

The analysis of the correlations by country (see Table 3) shows a significant relationship between type of source and trust in all countries [France (r = -0.140, p < 0.001), Greece (r = -0.195, p < 0.001), Italy (r = -0.144, p < 0.001), Portugal (r = -0.119, p < 0.001) and Spain (r = -0.190, p < 0.001)]. The relationship between the two variables is the same as in the pooled data, with digital media showing lower levels of trust. The main source of news has a significant positive correlation in Greece (r = 0.045, p = 0.047) and Portugal (r = 0.148, p < 0.001), implying that right-wing respondents prefer online media as their preferred source of news. Similarly, the Portuguese data shows a negative significant correlation between preferred news source and disinformation concern (r = -0.047, p = 0.038), behaving in the same way as the pooled data. Similarly, there was a significant relationship between ideology and disinformation concern in France (r = -0.046, p = 0.036), Portugal (r = -0.047, p = 0.034), and Spain (r = -0.074, p = 0.001). The correlation between ideology and overall trust in news was significant in France (r = -0.052, p = 0.019), Greece (r = 0.103, p < 0.001), Italy (r = -0.091, p < 0.001) and Portugal (r = -0.100, p < 0.001). Finally, disinformation concern also showed a significant negative relationship in France (r = -0.075, p = 0.001) and Greece (r = -0.082, p < 0.001).

Table 5: Spearman correlation analysis of key variables

|

POOLED |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

Type of source (1) |

1.000 |

,043** |

-,027** |

-,183** |

|

Ideology (2) |

,043** |

1.000 |

-,060** |

-,042** |

|

Disinformation concern (3) |

-,027** |

-,060** |

1.000 |

0.016 |

|

Trust (4) |

-,183** |

-,042** |

0.016 |

1.000 |

|

France |

|

|

|

|

|

Type of source (1) |

1.000 |

-0.006 |

-0.034 |

-,140** |

|

Ideology (2) |

-0.006 |

1.000 |

-,046* |

-,052* |

|

Disinformation concern (3) |

-0.034 |

-,046* |

1.000 |

-,075** |

|

Trust (4) |

-,140** |

-,052* |

-,075** |

1.000 |

|

Greece |

|

|

|

|

|

Type of source (1) |

1.000 |

,045* |

0.009 |

-,195** |

|

Ideology (2) |

,045* |

1.000 |

0.029 |

,103** |

|

Disinformation concern (3) |

0.009 |

0.029 |

1.000 |

-,082** |

|

Trust (4) |

-,195** |

,103** |

-,082** |

1.000 |

|

Italy |

|

|

|

|

|

Type of source (1) |

1.000 |

0.025 |

-0.008 |

-,144** |

|

Ideology (2) |

0.025 |

1.000 |

-0.029 |

-,091** |

|

Disinformation concern (3) |

-0.008 |

-0.029 |

1.000 |

-0.030 |

|

Trust (4) |

-,144** |

-,091** |

-0.030 |

1.000 |

|

Portugal |

|

|

|

|

|

Type of source (1) |

1.000 |

,148** |

-,047* |

-,119** |

|

Ideology (2) |

,148** |

1.000 |

-,047* |

-,100** |

|

Disinformation concern (3) |

-,047* |

-,047* |

1.000 |

0.038 |

|

Trust (4) |

-,119** |

-,100** |

0.038 |

1.000 |

|

Spain |

|

|

|

|

|

Type of source (1) |

1.000 |

0.031 |

-0.042 |

-,190** |

|

Ideology (2) |

0.031 |

1.000 |

-,074** |

-0.030 |

|

Disinformation concern (3) |

-0.042 |

-,074** |

1.000 |

0.032 |

|

Trust (4) |

-,190** |

-0.030 |

0.032 |

1.000 |

Source: Own elaboration based on Reuters Institute Digital News Report survey (2023).

3.4.3. Moderated mediation analysis

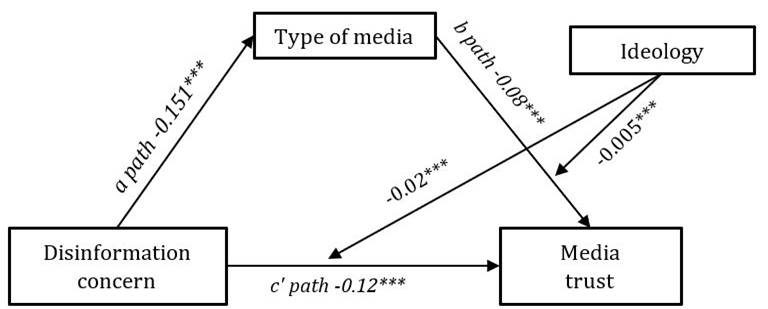

The complete model consisted of two regression sub-models. In the first regression, the influence of disinformation concern on type of news source was analysed. The pooled results across the five countries of our analysis proved the a path of our model was statistically significant, thus demonstrating a negative relationship between disinformation concern and type of news source (b = -0.151, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001). Therefore, we can assume that disinformation concern has a significant effect on our mediator variable (type of news source).

Our second regression model was more complex and involved all four variables and their relationships. On the one hand, we tested the significance of the relationship of our independent variable, disinformation concern, on our dependent variable, media trust. In other words, the c’ path of our model. On the other hand, we also tested the b path of our model, the relationship between our mediator variable and the dependent variable and the influence of our moderator variable. Our results suggest that disinformation concern exerts a statistically significant effect on trust on news (b = 0.12, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001). The same happens with the relationship between type of news source and media trust (b = -0.08, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001). Similarly, the interaction terms in both cases are also statistically significant. The interaction term for the c’ path is (b = -0.02, SE = 0.005, p <0.001), while the interaction term of the b path is (b = 0.005, SE = 0.001, p < 0.001).

The analysis revealed that the indirect effect of disinformation concern on trust in the media, mediated by type of news source, is not constant but depends on ideology. At low levels, the indirect effect is positive and significant (b = 0.0100, SE = 0.003, CI = 0.005, 0.015), however, as ideology increases, this is, right-leaning respondents (e.g., to 8), this indirect effect weakens and becomes negative and significant (b = -0.005, SE = 0.002, CI = 0.003, 0.008), indicating a reversal of the effect.

Figure 2: Model of moderated mediation. PROCESS Model 15

Source: Own elaboration based on Hayes (2022)

4. Discussion and conclusions

This study investigates how the type of news source (M) used by audiences mediates the relationship between disinformation concern (Y) and the overall media trust (X). Furthermore, we also analyse how «ideology» exerts different types of moderating effects: a direct effect (c' path) between our independent variable (X) and our dependent variable (Y), and on the indirect effect generated from the relationship between our independent variable (X) and the mediator variable (M). From the validation of the statistically significant model, we propose the following conclusions.

Firstly, the data reveal that people who are more concerned about disinformation tend to trust the media less (H1). Through the c'path of the proposed model, we validate the relationship between «disinformation concern» and «media trust». Our results indicate that heightened disinformation concern significantly decreases trust in the news.

The relationship between journalism and accuracy can have several consequences. First, when journalistic accuracy is compromised, it can contribute to expanded skepticism and cynicism among audiences (Tsfati & Cappella, 2003). This in turn can fuel anti-establishment attitudes often associated with populism (Markov & Min, 2023; Tsfati & Cohen, 2005). The implications of this phenomenon are significant for democracy, as it highlights the ongoing struggle for attention within the media landscape. Trust issues affect both individuals and society. Consequently, the tensions within the media structure create an environment fertile for the spread of disinformation that can disrupt the public sphere. One of the consequences of this disruption is the growing consumption of alternative media by certain audiences. These alternative media platforms vary in nature and present different ideological resources that can influence perceptions of democracy and the overall governance system.

Secondly, the data confirmed a significant relationship between «disinformation concern» and «type of media». Therefore, those individuals highly concerned about disinformation tend to increase their consumption of legacy media sources (traditional press, radio, or television) (H2). Through the a path of the proposed model, we validate the relationship. Concern about this phenomenon significantly influenced the selection of news sources, showing a negative relationship.

Academic literature shows that perceptions of disinformation are related to reduced trust in the news media (Hameleers et al., 2022). This indicates that individuals perceive legacy media coverage and their journalistic practices as more reliable. Resorting to traditional sources presents an alternative to counteract the impacts of incomplete, absent, and inaccurate information. Greater trust in legacy media is attributed to the presence of established journalistic standards and practices (e.g. fact-checking). Audiences may attribute to the press, radio, or television more objectivity, rigour, and credibility in news coverage.

Thirdly, our research supports that those individuals who use online sources of information, such as social networks, show higher levels of distrust compared to those who consume traditional media (press, radio and television) (H3). The rise of the new hybrid media system has led to growing distrust of online media due to concerns about possible reporting bias, inaccuracy, and loss of interest. This suggests that online media may contribute to extended disinformation concerns due to the prevalence of fake news and misinformation. These findings align with other investigations into disinformation, such as Zimmermann and Kohring (2020).

Fourth, ideology within the political spectrum (left, centre and right) moderates the relationship between «disinformation concern» and «media trust» (H4). Additionally, it also causes this moderating effect between the variables «type of media» and «media trust» (H5). Consequently, among left-leaning respondents, a rise in disinformation concern is associated with a preference for consuming online media or social networks. This trend leads to an increase in media trust among left-leaning users. Academic literature suggests that people polarised along the political spectrum are more susceptible to disinformation, which explains the spread of alternative sources that reinforce their pre-established ideas (Freelon et al., 2022; Harper y Sykes, 2023).

On the other hand, when ideology glides towards more right-leaning positions, the indirect effect becomes negative. We can therefore assume that for these users, the mediator variable behaves differently. Consequently, we do not observe such an enhanced effect between type of media source and trust for right leaning media users. These findings highlight the importance of considering moderators when analysing mediation, as the influence of one variable on another can be contingent on other factors in the system.

It is important to highlight some inherent limitations of our study. First, we analysed data from an online survey, which, while representative, cannot be extrapolated to the entire population of the five countries. In addition, we must consider the limitations of the variable «media trust». As Vara-Miguel et al. (2023) point out in a preliminary study on moderated mediation, the use of a single question to measure this phenomenon does not allow us to identify its multidimensional nature. Similarly, asking about trust also assumes every user understands this issue in the same fashion, which can indeed be understood from many different perspectives. Even if every user understood trust in the same way, a single question may fall short as to capture all the intricacies behind users’ level of trust. Another aspect to consider is that the political ideology variable is measured at three levels (left, centre and right). This could result in responses biased towards the political centre and not reflect the ideological complexity of the audiences or the political conditions of the five countries. Despite these limitations, our study contributes to the field by emphasising the moderating effect of this variable, an aspect that has not been widely explored in previous studies.

It is important to acknowledge that the sample used in this study is derived from an online survey. While Internet penetration is higher in the selected countries, it is worth noting that the sample may not represent the entire population. Additionally, surveys relying on recall, like the one used in this study, may not always provide a completely accurate picture of individuals' actual news consumption and media usage. However, despite these limitations, conducting a survey remains a practical and reasonable option for addressing our hypotheses and research questions.

References

Abramowitz, A., & McCoy, J. (2019). United States: Racial Resentment, Negative Partisanship, and Polarization in Trump’s America. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 681(1), 137-156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716218811309

Amoedo, A., Moreno, E., Negredo, S., Kaufmann-Argueta, J. & Vara-Miguel, A. (2023). Digital News Report España 2023. Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Navarra. https://doi.org/10.15581/019.2023

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics. Oxford University Press.

Carlson, M. & Lewis, S. C. (eds.). (2015). Boundaries of Journalism: Professionalism, Practices and Participation. Routledge.

Chadwick, A. (2013). The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power. Oxford University Press.

Edelman (2023). Edelman Trust Barometer. Navigating a polarized world. https://www.edelman.com/trust/2023/trust-barometer

Eisenstadt, S. N., & Roniger, L. (1984). Patrons, clients and friends: Interpersonal relations and the structure of trust in society. Cambridge University Press.

Engelke, K. M., Hase, V., & Wintterlin, F. (2019). On measuring trust and distrust in journalism: Reflection of the status quo and suggestions for the road ahead. Journal of trust research, 9(1), 66-86.

Fawzi, N., Steindl, N., Obermaier, M., Prochazka, F., Arlt, D., Blöbaum, B., Dohle, M., Engelke, K. M. Hanitzsch, T., Jackob, N., Jakobs, I., Klawier, T., Post, S., Reinemann, C., Schweiger, W. & Ziegele, M. (2021). Concepts, causes and consequences of trust in news media - a literature review and framework. Annals of the international communication association, 45(2),154-174. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2021.1960181

Fletcher, R. & Park, S. (2017). The impact of trust in the news media on online news consumption and participation. Digital journalism, 5(10), 1281-1299. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1279979

Freelon, D., Bossetta, M., Wells, C., Lukito, J., Xia, Y., & Adams, K. (2022). Black trolls matter: Racial and ideological asymmetries in social media disinformation. Social Science Computer Review, 40(3), 560-578. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439320914853

Garusi, D. & Splendore, S. (2023). Advancing a qualitative turn in news media trust research. Sociology compass, 17(4), e13075. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.13075

Gil De Zúñiga, H., Ardèvol-Abreu, A., Diehl, T., Gómez-Patiño, M. & Liu, J. H. (2019). Trust in institutional actors across 22 countries. Examining political, science, and media trust around the world. Revista latina de comunicación social, 74, 237-262. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2019-1329

Ha, L., Perez, L. A., & Ray, R. (2019). Mapping recent development in scholarship on fake news and misinformation, 2008 to 2017: Disciplinary contribution, topics, and impact. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 290–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219869402

Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge University Press.

Hameleers, M., Brosius, A, & De-Vreese, C. H. (2022). Whom to trust? Media exposure patterns of citizens with perceptions of misinformation and disinformation related to the news media. European Journal of Communication, 37(3),237-268. https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231211072667

Hanitzsch, T., van Dalen, A., & Steindl, N. (2018). Caught in the nexus. A comparative and longitudinal analysis of public trust in the press. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161217740695

Harper, S., & Sykes, T. (2023). Conspiracy Theories Left, Right and... Centre: Political Disinformation and Liberal Media Discourse. New Formations, 109, 110-128.

Hawley, K. (2012). Trust: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0610

High Level Expert Group on Fake News and Disinformation (HLEG). (2018). A multi-dimensional approach to disinformation: Report of the independent high level group on fake news and online disinformation. European Commission. https://tinyurl.com/3hjf968y

Holton, A. E., & Chyi, H. I. (2012). News and the overloaded consumer: Factors influencing information overload among news consumers. Cyberpsychology, behavior, and social networking, 15(11), 619-624.

Hovland, C. I. & Weiss, W. (1951). The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 15(4), 635-650. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2745952

Humprecht, E., Esser, F. & Van-Aelst, P. (2020). Resilience to online disinformation: a framework for cross-national comparative research. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(3), 493-516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219900126

Igartua,

J. -J., & Hayes, A. F. (2021). Mediation, moderation, and conditional

process analysis: Concepts, computations, and

some common confusions. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 24. e49. https://doi.org/0.1017/SJP.2021.46

Jack, C. (2017). Lexicon of lies: Terms for problematic information. Data & Society, 3, https://datasociety.net/library/lexicon-of-lies/

Kalmoe, Nathan P., and Lilliana Mason. (2019). «Lethal Mass Partisanship: Prevalence, Correlates, and Electoral Contingencies». Paper presented at the 2019 NCAPSA American Politics Meeting, Washington, DC.

Kohring, M. & Matthes, J. (2007). Trust in news media: development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Communication research, 34(2), 231-252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650206298071

Lee, T-T. (2010). Why they don’t trust the media: An examination of factors predicting trust. American Behavioral Scientist, 54(1), 8-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764210376308

Levendusky, M. S. (2010). Clearer Cues, More Consistent Voters: A Benefit of Elite Polarization. Political Behavior 32, 111–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-009-9094-0

Lucassen, T. & Schraagen, J. M. (2012). Propensity to trust and the influence of source and medium cues in credibility evaluation. Journal of information science, 38(6), 566-577. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551512459921

Magallón-Rosa, R. (2022): De las fake news a la polarización digital. Una década de hibridación de desinformación y propaganda. Revista Más Poder Local, 50, 49-65. https://doi.org/10.56151/maspoderlocal.120

Markov, Č., & Min, Y. (2023). Unpacking public animosity toward professional journalism: A qualitative analysis of the differences between media distrust and cynicism. Journalism, 24(10), 2136-2154. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849221122064

Medina, M., Etayo-Pérez, C. & Serrano-Puche, J. (2023). Categorías de confianza para los informativos televisivos e indicadores para su medición: percepciones de grupos de interés en Alemania, España e Italia. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 14(1), 307-324. https://www.doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM.23416

Meyer, P. (1988). Defining and measuring credibility of newspapers: developing an index. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 65(3), 567-574. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769908806500301

Miller, M. L., & Vaccari, C. (2020). Digital threats to democracy: Comparative lessons and possible remedies. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(3), 333–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220922323

Moran, R. & Nechushtai, E. (2022). Before reception: trust in the news as infrastructure. Journalism, 24(3), 457-474. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849211048961

Müller, P., & Schulz, A. (2021). Alternative media for a populist audience? Exploring political and media use predictors of exposure to Breitbart, Sputnik, and CO. Information, Communication & Society, 24(2), 277-293. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2019.1646778

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Eddy, K., Robertson, C. T., & Nielsen, R. K. (2023). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023. Reuters Institute for the study of Journalism.

Pérez-Latre, F. J. (2022). Crisis de confianza (2007-2022). El descrédito de los medios. Eunsa.

Perry, J. (2021). Trust in public institutions: trends and implications for economic security. Policy brief n. 108. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. http://tinyurl.com/2k6dhrhm

Pew Research Center (2022). Trust in government: 1958-2022. Pew Research Center. http://tinyurl.com/5n7zp43x

Prochazka, F. & Schweiger, W. (2019). How to measure generalized trust in news media? An adaptation and test of scales. Communication Methods and Measures, 13(1), 26-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2018.1506021

Quiring, O., Ziegele, M., Schemer, C., Jackob, N., Jakobs, I., & Schultz, T. (2021). Constructive skepticism, dysfunctional cynicism? Skepticism and cynicism differently determine generalized media trust. International Journal of Communication, 15, 22.

Ren, J., Dong, H., Popovic, A., Sabnis, G., & nickerson, J. (2024). Digital platforms in the news industry: how social media platforms impact traditional news viewership. European journal of information systems, 33(1), 1-18.

Sapienza, E. (2021). Trust in public institutions. A conceptual framework and insights for improved governance programming. United Nations Development Programme. http://tinyurl.com/3embvhza

Schranz, M., Schneider, J., & Eisenegger, M. (2018). Media trust and media use. In: Otto, K. & Köhler, A. (eds.). Trust in media and journalism: Empirical perspectives on ethics, norms, impacts and populism in Europe (pp. 73-91). Springer.

Serrano-Puche, J., (2017). Credibilidad y confianza en los medios de comunicación: un panorama de la situación en españa. In: González, M. & Valderrama, M. (eds.). Discursos comunicativos persuasivos hoy (pp. 427-438). Tecnos.

Serrano-Puche, J., Rodríguez-Salcedo, N. & Martínez-Costa, M.P. (2023). Trust, disinformation, and digital media: Perceptions and expectations about news in a polarized environment. Profesional de la información, 32(5), e320518. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2023.sep.18

Stamm, K. & Dube, R. (1994). The Relationship of Attitudinal Components to Trust in Media. Communication Research, 21(1), 105-123. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365094021001006

Strömbäck, J., Tsfati, Y., Boomgaarden, H., Damstra, A., Lindgren, E., Vliegenthart, R. & Lindholm, T. (2020). News media trust and its impact on media use: toward a framework for future research. Annals of the International Communication Association, 44(2), 139-156. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2020.1755338

Tsfati, Y. & Ariely, G. (2014). Individual and contextual correlates of trust in media across 44 countries. Communication research, 41(6), 760-782. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650213485972

Tsfati, Y. & Cappella, J. N. (2003). Do people watch what they do not trust? Exploring the association between news media skepticism and exposure. Communication Research, 30(5), 504-529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650203253371

Tsfati, Y. & Cohen, J. (2005). Democratic consequences of hostile media perceptions. The case of Gaza settlers. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 10(4): 28–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1081180X05280776

Uscinski, J.E., Enders, A.M., Seelig, M.I., Klofstad, C.A., Funchion, J.R., Everett, C., Wuchty, S., Premaratne, K. and Murthi, M.N. (2021), American Politics in Two Dimensions: Partisan and Ideological Identities versus Anti-Establishment Orientations. American Journal of Political Science, 65, 877-895. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12616

Vaccari, C. & Chadwick, A. (2020). Deepfakes and disinformation: exploring the impact of synthetic political video on deception, uncertainty, and trust in news. Social Media + Society, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120903408

Van-Aelst, P., Strömbäck, J., Aalberg, T., Esser, F. (2017). Political communication in a high-choice media environment: a challenge for democracy? Annals of the international communication association, 41(1), 3-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2017.1288551

Vara-Miguel, A. (2018). Confianza en noticias y fragmentación de mercado: el caso español. Comunicació: revista de recerca i d’anàlisi, v. 35(1), 95-113. https://doi.org/10.2436/20.3008.01.168

Vara-Miguel, A., Amoedo, A., Moreno, E., Negredo, S. & Kaufmann, J. (2022). Digital News Report España 2022. Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Navarra. https://doi.org/10.15581/019.2022

Vara-Miguel, A., Medina, M. & Gutiérrez-Rentería, M.E. (2023). Influence of news interest, payment of digital news, and primary news sources in media trust. A moderated mediation model. Journal of Media Business Studies, 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2023.2214447

Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policymaking. Council of Europe. https://tinyurl.com/5hxdu9cr

Watkins, J. Park, S. & Fisher, C. (2017). Digital news report: Australia 2017 (News and Media Research Centre (UC)). Accessed 8 3 2024. https://apo.org.au/node/95161

Webster, J. G. (2014). The marketplace of attention: How audiences take shape in a digital age. Mit Press.

Williams, A. E. (2012). Trust or bust? Questioning the Relationship between media trust and news attention. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56(1), 116-131. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2011.651186

Zimmermann, F. & Kohring, M. (2020). Mistrust, disinforming news, and vote choice: a panel survey on the origins and consequences of believing disinformation in the 2017 German parliamentary election. Political Communication, 37(2), 215-237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1686095