index●comunicación

Revista científica de comunicación aplicada

nº 15(1) 2025 | Pages 207-232

e-ISSN: 2174-1859 | ISSN: 2444-3239

Engagement and Purchase Intention in Storydoing and Storytelling for Instagram Ads

‘Engagement’ e intención de consumo en anuncios ‘storydoing’ y ‘storytelling’ para instagram

Received on 22/04/2024 | Accepted on 10/07/2024 | Published on 15/01/2025

https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/15/01Engage

Antonio Rodríguez-Ríos | Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

toni.rodriguez@uab.cat | https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7758-1953

Patrícia Lázaro Pernias | Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

patricia.lazaro@uab.cat | https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5633-7612

Abstract: People are committed to environmental issues, an aspect that forces organizations to address society in a more honest way. In this context, storydoing is presented as a communication model that questions those strategies based on lovebrands and responds to the demands of a society sensitized to social injustices. The aim of this work is to measure the rate of engagement and consumption intention generated by storydoing creativities compared to storytelling and to contribute to establish a theory about advertising based on narrative patterns. To this end, an experimental methodology has been applied to determine which of the two generates more engagement and consumption intention in Instagram users. The results show that the value with which they perceive the storytelling piece generates high rates of engagement with the advertised service.

Keywords: Storytelling; Storydoing; Engagement; Purchase Intention; Social Media; Experimental Reseach.

Resumen: Las personas están comprometidas con las cuestiones medioambientales, un aspecto que obliga a las organizaciones a dirigirse a la sociedad de forma más honesta. En este contexto, el storydoing se presenta como un modelo de comunicación que cuestiona aquellas estrategias basadas en las lovebrands y que responde a las demandas de una sociedad sensibilizada con las injusticias sociales. Este trabajo tiene como fin medir el índice de engagement e intención de consumo que generan las creatividades storydoing frente a las storytelling y contribuir a establecer una teoría en torno a la publicidad basada en patrones narrativos. Para ello, se ha aplicado una metodología de carácter experimental para determinar cuál de las dos genera más engagement e intención de consumo en usuarios de Instagram. Los resultados muestran que el valor con el que estos perciben la pieza storydoing genera altos índices de compromiso con el servicio publicitado.

Palabras clave: storytelling; storydoing; engagement; intención de consumo; redes sociales; investigación experimental.

To quote this work: Rodríguez-Ríos, A. y Lázaro Pernias, P. (2025). Engagement and Purchase Intention in Storydoing and Storytelling for Instagram Ads. index.comunicación, 15(1), 207-232. https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/15/01Engage

1. Introduction

The emergence of Web 2.0 and social media has favored a change in the behavior, uses, and skills of people who consume digital media and social networks, which has resulted in the creation of new models of information transmission (Núñez-Gómez et al., 2012). In December 2020, Instagram reached 2 billion active users worldwide and is currently one of the most followed networks (IAB, 2022; Fernández, 2023). It is therefore not surprising that brands are present in these media, which leads to their users taking an active role in generating content.

As a result, people who are sensitive to social and environmental injustices find a loudspeaker to convey their views to the world at large, including questioning the practices of their own organization. Consequently, brands have started to work on their identity and image in order to convey meaning and value to their target audience through strategies based on brand storytelling. According to Aaker (2014) and Costa (2018), storytelling gives brands a distinctive identity that helps to establish a close relationship with their audience.

However, some studies recently found that 58% of the content generated by brands is not meaningful to society. Moreover, they are not able to attribute it to a specific brand (Meaningful Brands, 2019). This makes us go beyond the communicative strategies of lovemarks ―brands based on mystery, sensuality, and intimacy (Roberts, 2005)― such as storytelling, and propose others that respond to the needs of today's society (Montague, 2013; Vallance, 2017; Fischer-Appelt & Dernbach, 2022). In this context, we propose storydoing as a disruptive strategic tool that responds to the demands of an audience that is much more committed to the planet and trusts brands to exercise activism.

The main objective of this work is to measure the engagement and purchase intention generated by advertising messages created through storydoing proposals in the social media audience. To this end, the aim is to analyze how stories are articulated in advertising through -doing (O1), to find out how Instagram users behave when faced with storydoing campaigns (O2), and to find out what engagement in social media consists of (O3).

1.1. Storytelling

The term storytelling, far from its application in marketing and advertising, concerns the exercise of narrating, whether orally or in writing. The National Storytelling Network (NSN) describes it on its website as the interactive art of using words and actions to reveal the elements and images of a story while encouraging the imagination of the listener. The Federation for European Storytelling (FEST) agrees with this, but incorporates technological means of communication as key players in sharing interactivity between people in real time. Both organizations aim to promote the mobility of ideas and collaborations with the goal of raising awareness and transforming the current realities in the United States and Europe, respectively.

Considering storytelling as a way of transforming lives is a broad definition whose versatility makes it applicable to different disciplines. In his doctoral thesis, Vizcaíno (2016) collects more than 30 definitions of storytelling from 1987 to 2015 in the fields of education, theology, management, sociology, politics, and anthropology. These definitions were expanded after a study of the 2016-2023 period, with further fields added such as health sciences, specifically medicine and psychology (Rodríguez-Ríos, 2024).

This transversality can be explained by what Schank and Abelson (1995) already pointed out in their research on the psychology of storytelling. From the perspective of cognitive psychology, the creation and transmission of stories is understood as the basis on which human memory is built. The process by which we tell stories originates in the indexing of stories in our brains, and then activating, adapting and sharing them in the act of conversing with another person. This is based on the activity led by humans over more than 100,000 years in order to find meaning in life, but also their identity in society (Sánchez, 2011; Gottschall, 2013). This is an aspect that advertising imitates when working on the identity and image of brands, products and services.

1.1.1. Storytelling in Advertising

The concept of storytelling, as we know it today, stems from David Ogilvy after he showed interest in the concept of story appeal, coined by Rudolph in his study Attention and interest factor in advertising survey analysis interpretation. This focuses on the curiosity aroused by certain advertising images and how people turn to the text to satisfy it. From this point on, the sympathy for the finding was such that advertisers began to refer to these texts with the term storytelling (Mercé, 2014; Woodside & Sood, 2016).

Dange (2018) points out that storytelling in marketing and advertising starts with an initial situation where the individual is presented with a problem to solve, actions that challenge their solution, and characters that carry them out until culminating in an ending. This structure is reminiscent of Minto's (2009) top-down pyramid model, based on engaging the audience through a generic situation, followed by a specific problem, the formulation of more specific questions, and the final solution.

Other researchers, instead of focusing on the structure, address the emotional charge that a good story must contain. According to Guber (2011), the appeal of storytelling is to emotionally transport the audience in such a way that they are not even aware of receiving a commercial message. This state leads the audience to act impulsively, driven by a call to action that the narrative voice is responsible for enunciating (Laurence, 2018).

Connotative advertising means that professionals in the sector rely on emotion, but also on persuasion, as the driving force behind a good campaign (Sánchez-Corral, 2009). Hence, they are starting to work on the argumentative force as a channel that guides the brand in the pursuit of its objectives. In this sense, rhetoric also occupies a fundamental place, as it has the power to influence the beliefs, attitudes and behavior of its audience. To this end, this language technique often uses the target's frustrations to elaborate suggestive discourses that extol the brand promise as a unique solution (Spang, 2005).

On the other hand, McKee (2009) warns that people generate high doses of empathy when they become emotionally involved with a fictional character. In fact, some scholars such as Ballester and Sabiote (2016) highlight their importance when measuring the quality of a good story, as they have the ability to generate plot twists that move the plot forward. So much so that some scholars warn that events are precisely developed from the characters: «the heart, soul and nervous system of a script» (Field, 2001: 49).

In sum, although critics have pointed out the difficulty of establishing a single definition of the term storytelling, there are some characteristics that could contribute to it. Among them, the structure, emotions, rhetoric, and characters mentioned in this section are presented as strategic components that elevate storytelling to the category of a strategic advertising tool.

1.2. From Storytelling to Storydoing

Some analysts saw 2017 as the year of marketing transformation (Winsor, 2017); hence questions began to be asked about what brands are doing for society (Vallance, 2017). These questions would ultimately reinforce public opinion on the role of organizations in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Edelman study (2020) found that 89% of respondents believe that companies should help people in trouble, especially as a result of having experienced confinement.

It is then that activist brands appear. By using storytelling, these brands manage to show their affinity with a given socio-political debate and, consequently, acquire relevance and strengthen relations with an audience (Selva-Ruiz, 2024: 111).

From this point onwards, more and more studies and research are discussing the global role that organizations are assuming towards consumers (Raimondo et al., 2022). In addition to brand activism, this aspect is reflected in advertising strategies that begin to consider a social or environmental purpose, empathize with the concerns of a new consumer, and ensure the effectiveness of their communication strategies.

Within this framework, in the United States and Latin America, a series of companies that present themselves to the world with a purpose, usually of a social nature, are emerging. They are known as storydoing companies (De-Miguel-Zamora & Toledano-Cuervas, 2018). The novelty of the term lies in the story, as it contains a tool proposed by the brand so that the audience, making use of it, can put it into practice. These can be digital platforms with sophisticated algorithms, mobile applications, web pages with forms, video games, short films, events, the downloading of valuable content, etc. (Rodríguez-Ríos & Lázaro Pernias, 2023).

In this sense, it could be considered a refined model of storytelling that, far from being used solely as a tool for building brands, is employed to communicate their assets. To this end, it is essential to consider the three pillars on which this communication model is based - purpose, brand assets, and brand amplification (Baraybar & Luque, 2018).

Purpose is given by the quest undertaken by organizations, which becomes the ambition that drives them to contribute to the world. In other words, it is «the aspirational mission of the company, brand or product beyond making money» (Montague, 2013: 54).

The definition of the purpose implies that the brand must clearly demonstrate its commitment to society through its actions or assets, such as products, services, or unique experiences. Consequently, it is a communication model whose value proposition is imprinted in the way it acts, not in the way it communicates.

The amplification of the brand is given by the use of storytelling to communicate the existence of the aforementioned assets. It is at this point that storytelling adopts a special role in the strategic gearing of storydoing. However, while the media landscape has traditionally been established in paid media, owned media, and earned media, storydoing represents a turning point by proposing an action that originates in owned media, which continues through earned media, and to a lesser extent, through paid media (Baraybar & Luque, 2018).

Storydoing, as opposed to philanthropic marketing, is understood as an innovative practice that encourages commercial organizations to launch social messages that are part of their identity. Also, it is characterized by involving people in a cause and making them act as a character in the story, which generates high levels of engagement among its participants.

1.3. Engagement in Social Media

Tur-Viñes (2015) notes the difficulty of conceptualizing engagement given its emotional idiosyncrasies and the fact that it derives from a subjective feeling linked to how each individual perceives and feels reality. However, recent research points to it as a behavioral motivator which leads to sharing the experience that the person lives through their social networks. It is therefore understood as a relationship that consumers have with brands, which goes beyond commercial transactions, thanks to the involvement of cognitive and emotional processes that lead to a specific behavior (Davcik et al., 2022).

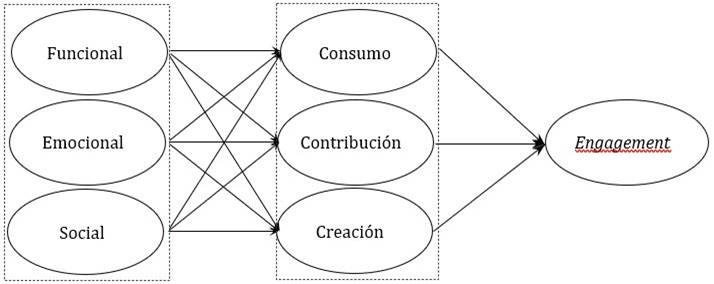

Dolan et al. (2016) talk about a type of behavior, called social media engagement behavior, which is embodied in the creation of content about a brand on social networks. This perspective is in line with others that analyze motivational behavior in relation to the value with which content is perceived on social networks. This can be functional, emotional, and social (Grewal et al., 2004; Jahn & Kunz, 2012; Kim et al., 2012; De Vries & Carlson, 2014). Whether the social network user likes, comments or shares, the content depends on this (Davcik et al., 2022).

Functional value is closely related to brand information content and reflects the perceived usefulness of the attributes offered in the brand, such as strategic value, efficiency, and operational and environmental benefits (Woodruff, 1997). Emotional value arouses or perpetuates feelings related to comfort, security, passion, fear, or guilt (Smith & Colgate, 2007). Perceived social value refers to content that supports social relationships, the formation of individuals' self-concept, and social self-identity (Christodoulides et al., 2012).

This is all illustrated in Figure 1, which features the theoretical model proposed by Davcik et al. (2022). This model will inspire us to measure engagement in storydoing and storytelling advertisements.

Figure 1. Theoretical model of engagement

Source: Davick et al. (2022).

1.4. Review of Theory of Uses and Gratifications

This theory has traditionally focused on the audience and how the media satisfy their needs related to social interaction (Martínez, 2010: 5). The interest in delving into the gratifications that media provide dates back to early research on mass media (Katz et al., 1973-74). However, in the 2000s, questions began to arise regarding what made users of so-called conventional media migrate to the use of digital social networks. Florenthal (2019) refers to hedonic motives, such as entertainment; utilitarian ones, such as information seeking; and also, social ones, such as personal utility. In fact, he points out that useful content in the form of storytelling is an attractive strategy that amalgamates both motives.

In sum, Florenthal's (2019) review of the theory of uses and gratifications revolves around three key ideas that enrich the existing model:

1. Motivational drivers

2. Engagement in digital media and social networks

3. Attitude and behavioral intention

Regarding the third rationale, Florenthal echoes the research of Dehghani et al. (2016) to point out that the engagement generated by branded content could be related to purchase intention (Florenthal, 2019: 379).

This led us to propose the following hypotheses for this research work:

─ H1: Storydoing creativities generate more engagement than storytelling creativities.

─ H2: The engagement generated by storydoing creativities impacts purchase intention.

2. Materials and Methods

This article presents the results of a research study consisting of a qualitative and an experimental phase. The first included an exploratory, primary, and horizontal content analysis of a 12-campaign sample in order to determine which narrative elements were involved in the content generated by Instagram users. The data from this phase was presented in quantitative form, since, as Gaitán and Piñuel (1995) state, the condition of content analysis is qualitative. This is because it is based on a theoretical framework with which the analytical categories used are specified, although quantitative techniques (counting frequencies) are applied for data analysis.

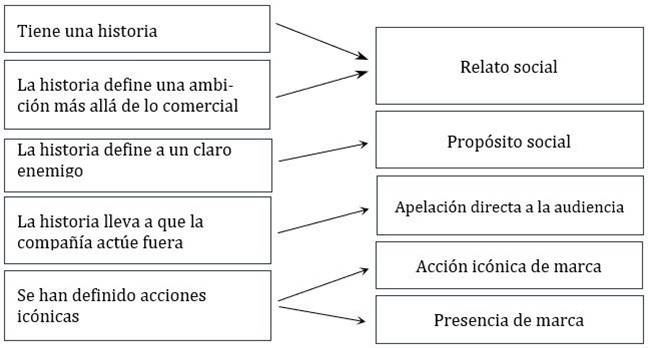

To narrow down the sample, analyzed 2.736 campaigns from Los Anuncios del Año and the Club de Creativos archive were first analyzed through a screening table that allowed us to identify those of a storydoing nature by the following items: a) The campaign has a story, b) The story defines an ambition beyond the commercial one, c) The story defines a clear enemy, d) The story leads the company to act out, e) A few iconic actions have been defined (Montague, 2013). Finally, 87 storydoing campaigns were eventually gathered.

However, given that our research focuses on Instagram, this 87-campaign sample was subjected to a purposive double check to find storydoing campaigns present on Instagram. In the end, as illustrated in Table 1, a 12-campaign sample was achieved.

Table 1. Sample content analysis

|

Brand |

Campaign |

|

Ruavieja |

Tenemos que vernos más |

|

Heineken ES |

#FuerzaBar |

|

Renault |

FeliZiudad |

|

Edp |

Comparte tu energía |

|

Ikea |

Desconecta para conectar |

|

Edp |

Sincronizadas |

|

Gillette |

Hay que ser muy hombre |

|

Ikea |

Salvemos las cenas |

|

Renfe |

La obra más cara |

|

McDonald's |

Big Good |

|

BBVA |

Yo soy empleo |

|

Samsung |

Dytective for Samsung |

Source: own elaboration.

The analysis of the content generated by Instagram users (UGC) allowed us to affirm that storytelling is part of the strategic gear of storydoing, as the users of this social network extend the brand story. This conclusion was reached based on the identification of different narrative elements reminiscent of Greimas' (1971) actantial system, the use of short and medium shots (Fernández & Martínez, 1999), and verbal anchors that are mostly conative (Ferraz, 2000; Rodríguez-Ríos, 2024).

On the other hand, given the exploratory nature of this phase, the results achieved allowed us to obtain some indications that would help us to carry out the experimental phase. Specifically, we were able to establish the categories to undertake a second content analysis and create an experimental stimulus as real as possible to a storydoing advertising piece. To do so, the sample from the first content analysis (N = 12) was used, and the elements present in their official publications were analyzed. As shown in Table 2, 7 common denominators were found in the advertising pieces that make up the sample.

Table 2. Relevant content of storydoing campaigns

|

Categories |

|

Social purpose |

|

Iconic brand action |

|

Brand presence |

|

Use of subjective framing |

|

Use of short and medium shots |

|

Social story |

|

Direct appeal to the hearing |

Source: own elaboration.

These results were compared with the campaign model proposed by Montague (2013) in his storydoing manifesto. The similarities found are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Similarities between the campaign content proposed by Montague (2013) and that resulting from content analysis

Source: own elaboration based on Montague (2013).

2.1. Development of the Stimulus

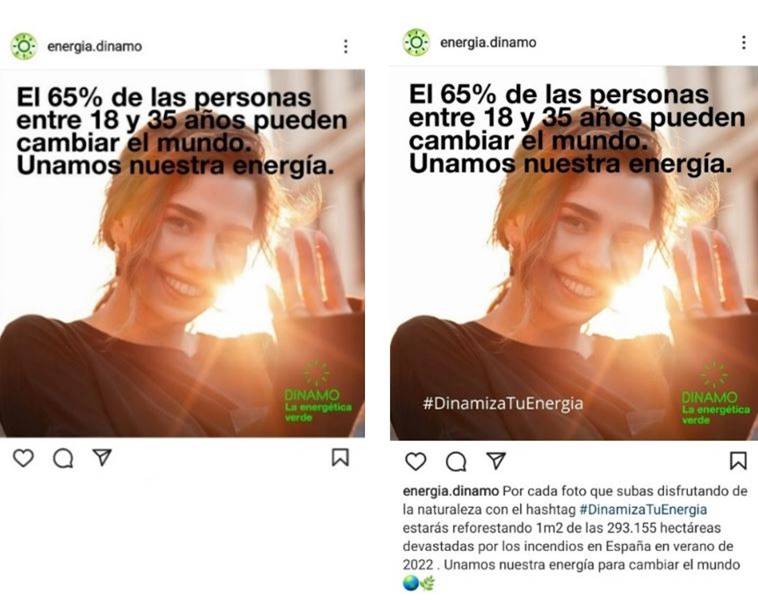

An Instagram storydoing piece and an Instagram storytelling piece were created for a fictitious brand in order to avoid any previous reputation towards already known brands. This is Dinamo, a green energy company aimed at creating a more sustainable world thanks to the good work of society.

The UNDP website states that 18-35-year-olds are the driving force behind making our planet a more sustainable place. This data was used to develop the story for both experimental stimuli.

This is based on Greimas’ (1971) actantial model, taking people aged 18-35 as the subject (SB), wanting to change the world as the object of desire they pursue (O), the Dynamo brand as the target of the proposal (S), the Instagram audience as the addressee (R), the implied climate change as the opponent of the equation (OP), and the collaboration with an NGO that carries reforestation as the helping element (H). Regarding the latter, not all campaigns on social media mention collaboration with foundations or NGOs, which is it was not made explicit. However, if it were a real campaign, we would encourage the target audience to visit the corporate website, where we have corroborated that the brands develop this issue.

However, to move from storytelling to storydoing, a branding tool was designed in the form of a hashtag and a brief instruction on how to use it: for each person who shared photos related to Spain's natural landscapes on their Instagram account, they would be helping to reforest 1m2 of the areas devastated by the fires in Spain in 2022.

As can be seen in Figure 3, compared to the storytelling stimulus, the storydoing stimulus has the independent variable mentioned above. Its manipulation will allow us to measure the engagement and the intention to consume that one generates compared to the other in the experiment.

Figure 3. Storytelling and storydoing stimuli

Source: own elaboration.

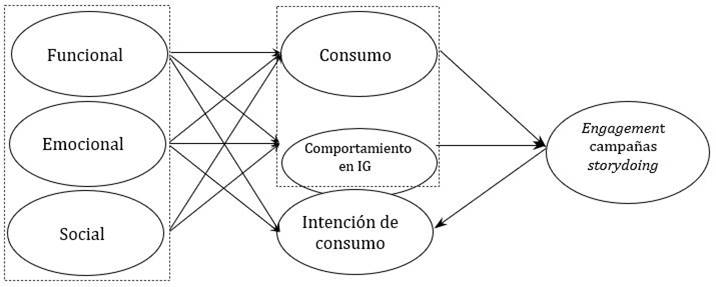

2.2. Measurement Scale

Based on the model proposed by Davcik et al. (2022), engagement was measured through functional, emotional, and perceived social value (α >0.8). However, as shown in Figure 4, the original model was adapted to our research by incorporating the dimensions of consumption and behavior on Instagram (α=0.925) (Valentini, 2018) and intention to engage (α=0.97) (Dodds & Monroe, 1991).

Figure 4. Proposed model for measuring engagement and intention to hire de service

Source: own elaboration.

In addition, an instructional manipulation test was added to provide reliability to the responses and avoid noise that could lead to irrelevant results. The subject was informed that many brands advertise on social networks, but the purchase was made through their website. The subject was then asked to tick the website option from a list containing the names of several social media.

As can be seen in Table 3, a 24-item questionnaire was created, with responses being measured on a seven-point Likert scale.

Table 3. Items to measure engagement and purchase intention

|

Dimension |

Sources |

Items |

|

Functional value (1-7)

|

Jahn and Kunz (2012), Davcik et al. (2022) and Grewal et al. (2004) |

It is practical |

|

It is useful to |

||

|

It is necessary to |

||

|

Emotional value (1-7) |

De Vries and Carlson (2014) and Davcik et al. (2022) |

It is pleasant |

|

It is entertaining |

||

|

It is exciting |

||

|

It's fun |

||

|

Social value (1-7) |

Kim et al. (2012) and Grewal et al. (2004) |

It helps me to feel in harmony with people |

|

The ad affects me socially |

||

|

Reflects the kind of person I see myself to be |

||

|

It makes me feel good about myself |

||

|

Brand consumption on social networks (1-7) |

Schivinki et al. (2016) |

The announcement makes me look forward to reading the posts |

|

The announcement makes me want to read fan pages |

||

|

The advert makes me want to watch branded videos |

||

|

The ad makes me want to read brand blogs |

||

|

The ad makes me want to follow the brand in SM |

||

|

Behavior (1-7) |

Valentini (2018) |

The announcement makes me want to respond on IG that I like it |

|

The advert makes me want to post a comment on IG |

||

|

The announcement makes me want to share it with my friends |

||

|

The ad makes me want to upload a video on IG |

||

|

The ad makes me want to use a hashtag on IG |

||

|

Intention |

Dodds and Monroe (1991) |

Contracting a service of this kind |

|

I would hire a service from this brand |

||

|

Intention to contract this service is high |

Source: own elaboration.

2.3. Sample

The 18-35-year-old Instagram users in the sample were selected through Amazon Mechanical Turk, a reliable crowdsourcing platform for studies in the field of advertising and endorsed by the scientific community as a result of the high quality of the data (Xu & Wu, 2016; Kim et al., 2016; Kees et al., 2017).

To calculate the sample size, previous research measuring some of the dimensions of engagement that informed this work was used as a reference. De Vries and Carlson (2014) acquired a sample of 452 participants, Jahn and Kunz (2012) of 526, and Kim et al. (2012) of 259. In our case, a sample consisting of 407 participants residing in Spain was achieved. 400 after excluding those who did not correctly answer the aforementioned instructional manipulation test, the final number was 400.

3. Analysis and Results

First of all, we will begin by describing the sample obtained through descriptive statistical procedures. The statistical software Jamovi, version 2.3.18, was used to conduct each of the tests.

As can be seen in Table 4, the sample consists of more female (51.7%) than male (46.5%) and neutral (1.8%) participants. However, as featured in Table 5, no statistically significant differences (p>0.05) were found in relation to the two groups into which the story variable was divided (-telling and -doing) (χ² (2, N=400) = 1.48, p=0.47).

Table 4. Gender

|

Frequencies |

% of total |

Accumulated |

|

|

Female |

207 |

51.7% |

51.7% |

|

Male |

186 |

46.5% |

98.3% |

|

Neutral |

7 |

1.8% |

100.0% |

Source: own elaboration.

Table 5. χ² test

Source: own elaboration.

Table 6 shows that the predominant level of education among the study participants is a university degree (43.5%) and a baccalaureate (18.5%). Based on this, it can be said that the profile of our population is undergoing academic training.

Table 6. The studies

|

Studies |

Frequencies |

% of total |

Accumulated |

|

Baccalaureate |

74 |

18.5% |

18.5% |

|

PhD |

8 |

2.0% |

20.5% |

|

Primary education |

5 |

1.3% |

21.8% |

|

Secondary education |

21 |

5.3% |

27.0% |

|

Intermediate level of education |

24 |

6.0% |

33.0% |

|

Higher education |

42 |

10.5% |

43.5% |

|

University degree |

174 |

43.5% |

87.0% |

|

Master's degree |

50 |

12.5% |

99.5% |

|

Uneducated |

2 |

0.5% |

100.0% |

Source: own elaboration.

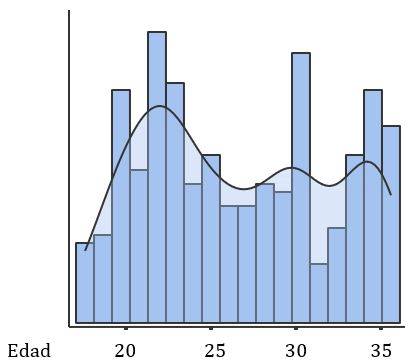

In terms of age, Figure 5 shows that the highest peaks occur at ages 22 and 30, with a mean age of 26 years (M=26.6, SD=5.19). This is relevant if we consider that the predominant level of education in the sample (N = 400) is a university degree (43.5%).

Figure 5. Age

Table 7. Marital status

|

Marital status |

Story- |

Frequencies |

% of total |

% accumulated |

|

Married

|

doing |

39 |

9.8% |

9.8% |

|

telling |

40 |

10.0% |

19.8% |

|

|

Divorced |

doing |

4 |

1.0% |

20.8% |

|

telling |

6 |

1.5% |

22.3% |

|

|

In a relationship |

doing |

56 |

14.0% |

36.3% |

|

telling |

51 |

12.8% |

49.0% |

|

|

Single |

doing |

104 |

26.0% |

75.0% |

|

telling |

100 |

25.0% |

100.0% |

Source: own elaboration.

Finally, the frequency of Instagram use is high. As indicated in Table 8, 72% access it a few times an hour (31.5%), once every two hours (21.3%), and a few times a week (19.3%).

Table 8. Time spent on Instagram

|

Time in IG |

Frequencies |

% of total |

% accumulated |

|

|

Never |

10 |

2.5% |

2.5% |

|

|

Once a week |

17 |

4.3% |

6.8% |

|

|

Once a year |

4 |

1.0% |

7.8% |

|

|

Once a month |

8 |

2.0% |

9.8% |

|

|

Once every two hours |

85 |

21.3% |

31.0% |

|

|

Once every hour |

58 |

14.5% |

45.5% |

|

|

A few times a week |

77 |

19.3% |

64.8% |

|

|

A few times a day |

9 |

2.3% |

67.0% |

|

|

A few times per hour |

126 |

31.5% |

98.5% |

|

|

Once every two months |

6 |

1.5% |

100.0% |

|

Source: own elaboration.

Next, statistical processing of the results was carried out (N = 400) by contrasting the hypotheses put forward in this research. All statistical tests were applied with a confidence level of 95%. The Jamovi statistical software, version 2.3.18, was again used to conduct each test.

As shown in Table 9, first, a simple linear correlation was carried out to measure the degree of joint variation between the variables in the experimental group -doing (n = 203) and the control group -telling (n = 197) (N = 400). After performing the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (p<0.05), we determined that there was no normality in the distribution of the data, which led us to conduct Spearman's correlation.

Table 9. Spearman’s Correlation

Correlation results between functional value and age were null, with a rho value (398) =.018, p= .724. However, high correlations were found between perceived emotional value and content consumption with a rho value(398) =.603, p=.001, perceived social value and content consumption with a rho value(398) =.629, p=.001, perceived emotional value and behavioral variable with a rho value(398) =.767, p=.001, perceived emotional value and intention to hire the service with a rho value(398) =.752, p=.001, and content consumption and intention to hire the service with a rho value(398) =.613, p=.001. Finally, it should be noted that the results of the correlation between the behavioral variable and the intention to hire the service were very high, with a rho value (398) =.860, p=.001.

This led us to reject H0 and accept H1:

─ H0: Storydoing creativities do not generate more engagement than storytelling creativities.

─ H1: Storydoing creativities generate more engagement than storytelling.

The more emotive and social the content is perceived to be, the more it is consumed. However, what really makes the audience interact with Instagram's functionalities is the emotionality with which the post is perceived. That is, the greater the dose of entertainment, amusement, enjoyment, and fun, the greater the desire to comment on the content, share it, or like it, among other manifestations.

Likewise, we rejected H0 and accepted H2:

─ H0: The engagement generated by storydoing creativities does not influence the intention to hire the service.

─ H2: The engagement generated by storydoing creativities impacts the intention to hire the service.

The more emotive the content is perceived to be, the greater the desire to consume it and purchase the advertised service. However, what makes Instagram users decide to purchase the service is the interaction with the publication itself. That is, the greater the interaction with the content, the greater the intention to purchase the advertised service.

Subsequently, we compared the means of the distributions of the quantitative variables in the two groups established by the qualitative variable story: -doing (n = 203) and the control group -telling (n = 197) (N = 400). As shown in Table 10, we applied Mann-Whitney’s U test to compare the means of the values that had generated the engagement and the intention to hire the service in each group.

Table 10. Comparison of means

|

Independent samples t-tests |

Est. |

p |

|

|

Functional value |

Mann-Whitney U test |

15493 |

<.001 |

|

Emotional value |

Mann-Whitney U test |

10853 |

<.001 |

|

Social value |

Mann-Whitney U test |

16316 |

0.001 |

|

Consumption |

Mann-Whitney U test |

17530 |

0.033 |

|

Behavioral |

Mann-Whitney U test |

11210 |

<.001 |

|

Intention to contract the service |

Mann-Whitney U test |

10450 |

<.001 |

Source: own elaboration.

As can be seen, the p-value was significant in each of the dimensions that make up the engagement variable (p<0.05). Therefore, H1 can be accepted with 95% confidence, and H0 can be rejected:

─ H0: Storydoing creativities do not generate more engagement than storytelling creativities.

─ H1: Storydoing creativities generate more engagement than storytelling creativities.

After this test, it can be stated that storydoing creativities generate more engagement than storytelling creativities.

Similarly, the p-value (p>0.05), with 95% confidence, led us to reject H2 and reject H0:

─ H0: The engagement generated by storydoing creativities does not impact purchase intention.

─ H2: The engagement generated by storydoing creativities impacts purchase intention.

This test also determined that the engagement generated by storydoing creativities impacts the intention to hire the service.

Therefore, it can be stated that storydoing creativities generate more engagement and intention to hire the service than storytelling creativities.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The main objective of this research was to analyze the evolution from storytelling to storydoing as a factor of engagement on social media. An experiment carried out in a sample of 400 participants determined that storydoing advertising pieces generate more engagement and purchase intention than storytelling pieces.

In his review of the theory of uses and gratifications, Florenthal (2019) points out that useful content, especially in storytelling format, involves social media users in high doses. In this sense, the design of the experimental stimulus sought to be useful and therefore proposed to contribute to the reforestation of the burned areas in Spain in 2022.

In relation to the first specific objective (O1), the implementation of a tool to combat deforestation in 2022 in the storytelling represents a new way of articulating the advertising narrative.

While the use of storytelling as an argumentative force is still effective (Sánchez-Corral, 2009), we have perceived that the presence of a social purpose connects with a society sensitized to social injustices. To achieve this purpose, the campaign proposes a branding tool that brings social media users into the real world to fight against a public enemy. For each Instagram post registered with the hashtag #DinamizaTuEnergía, Instagram users contribute by reforesting 1m2 of the areas of Castilla y León devastated by fires in 2022. This action is reminiscent of some success stories such as that of Sidra El Gaitero, when it set out to reforest the burnt areas of Asturias and part of Galicia in 2017 with its #DescorchaUnDeseo campaign.

Hence, we can point out that the new way in which advertising stories are articulated is through a tool that brands propose and place at the service of their audience, with which they can put the story outlined in the campaign into action.

Regarding the second specific objective (02), Instagram users perceive storydoing ads as more exciting and entertaining, which leads them to consume content and express their behavior through the functionalities of the relevant social network. These include liking, commenting, sharing content, uploading a video, and using the aforementioned branded hashtag. Therefore, it can be seen that the people who get involved with the storydoing pieces are predisposed to adopt a certain role in the story as if they were just another character. As Field (2001) and McKee (2009) point out, characters are the engine that drives any story forward, only this time we are dealing with a narrative model in advertising whose characters are embodied by the audience itself.

All of this provides empirical support for the theoretical model of engagement proposed in this paper. Davcik et al. (2022) already pointed out that the perception of a certain content directly influences behavior on social media. In fact, this research, in response to the third specific objective proposed (O3), corroborates these premises and confirms that engagement is a motivational driver that determines the behavior of social media users to the point of harboring the desire to consume.

Although the scientific community has labelled the conflation of commercial communication with the implementation of a social purpose as incoherent (Das et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020; Coleman, 2022), storydoing is presented as a disruptive model that amalgamates both aspects. In fact, research shows that consumers respond positively to companies' support for sustainable causes over time to the point of rewarding these efforts by making a purchase (Barone et al., 2000; Hwang & Kandampully, 2015;). Similarly, some authors stress that, regardless of the nature of the organization, it is the combined value that matters. That is, the organizational capacity to act holistically in the social and environmental sphere as well as in the financial one (Emerson & Bugg, 2011; Porter & Kramer, 2011).

Hence, we have to differentiate between opportunistic brand strategies based on a contextual situation and storydoing as a strategy that directs the organization’s actions and ultimately determines the identity and positioning of the brand itself.

As stated by Baraybar and Luque (2018), we are faced with a brand strategy that focuses on obtaining content generated by those who use social media. This aspect contributes to increasing the narrative proposed from the brand's own media through earned media, relegating investment in paid media to second place.

In light of this, we conclude that storydoing is a business and advertising communication tool based on a story that transcends the commercial, that detects and defines a problem in society, and that leads to the participation of stakeholders through actions proposed by the organization itself.

According to Edelman’s study (2020), after the coronavirus pandemic, society expects organizations to do something for society. Hence, the advertising industry in Spain is encouraged to consider the use of storydoing strategies in the development of future campaigns.

In this regard, although this research was carried out within the framework of Instagram, we believe that the results can be extrapolated to other social media, so it would be relevant to replicate the experiment in other social networks that are gaining awareness and notoriety, such as TikTok (IAB, 2022).

Ethics and Transparency

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Patricia Luján for her expertise in the art direction of the stimuli created for the experiment, and to SOMOS Traductores for proofreading the English version of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this work declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research has not been funded.

Author Contributions

|

Contribution |

Author 1 |

Author 2 |

Author 3 |

Author 4 |

|

Conceptualization |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Data curation |

X |

|

|

|

|

Formal Analysis |

X |

|

|

|

|

Funding acquisition |

|

|

|

|

|

Investigation |

X |

|

|

|

|

Methodology |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Project administration |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Resources |

X |

|

|

|

|

Software |

X |

|

|

|

|

Supervision |

|

X |

|

|

|

Validation |

|

X |

|

|

|

Visualization |

X |

|

|

|

|

Writing – original draft |

X |

|

|

|

|

Writing – review & editing |

X |

X |

|

|

Data Availability Statement

All data created for the experiment in this research is available at http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13880685

References

Aaker, D. (2014). Brands according to Aaker. 20 principles for success. Urano.

Ballester, E. & Sabiote, E. (2016). Once upon a Brand: storytelling practices by Spanish brands. Spanish Journal of Marketing-EDIC 20(2), 115-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjme.2016.06.001

Baraybar, A. y Luque, J. (2018). Nuevas tendencias en la construcción de marcas: una aproximación al storydoing. Prisma Social, (23), 435-458. https://tinyurl.com/2szcvav5

Barone, M. J., Miyazaki, A. D. & Taylor, K. A. (2000). The influence of cause-related marketing on consumer choice: Does one good turn deserve another? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 28(2), 248-262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070300282006

Christodoulides, G., Jevons, C. & Bonhomme, J. (2012). Memo takers: quantitative evidence for change - how user-generated content really affects brands. Journal of Advertising Research, 52(1), 53-64. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-52-1-053-064

Coleman, J. (2022). Giving over selling: advertising for the social enterprise. Journal of business strategy, 44(4), 191-199. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBS-11-2021-0179

Costa, J. (2018). Creación de la Imagen Corporativa. El Paradigma del Siglo XXI. Razón y Palabra, 22(1-100), 356-379. https://tinyurl.com/2syk78dh

Dangel, S. (2018). Storytelling práctico para mejorar tu comunicación. Amat Editorial.

Das, G., Mukherjee, A. & Smith, R. J. (2018). The perfect fit: the moderating role of selling cues on hedonic and utilitarian product types. Journal of Retailing, 94(2), 203-216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2017.12.002

Davcik, N. S., Langaro, D., Jevons, C. & Nascimento, R. (2022). Non-sponsored brand-related user-generated content: effects and mechanisms of consumer engagement. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 31(1), 163-174. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2020-2971

De-Miguel-Zamora, M. y Toledano-Cuervas, F. (2018). Storytelling y storydoing: técnicas narrativas para la creación de experiencias publicitarias. En F. García, V. Tur Viñes, I. Arroyo y L. Rodrigo (Coord.), Creatividad en publicidad: Del impacto al comparto (pp. 215-232). Dykinson.

De Vries, N. J. & Carlson, J. (2014). Examining the drivers and brand performance implications of customer engagement with brands in the social media environment. Journal of Brand Management, 21(6), 495-515. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2014.18

Dehghani, M., Niaki, M. K., Ramezani, I. & Sali, R. (2016). Evaluating the influence of YouTube advertising for attraction of young customers. Computers in Human Behavior, 59, 165-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.01.037

Dodds, W. B., Monroe, K. B. & Grewal, D. (1991). Effects of Price, brand and store information on buyer’s product evaluations. Journal of Marketing Research, 28(3), 307-319. http://doi.org/10.2307/3172866

Dolan, R., Conduit, J., Fahy, J. & Goodman, S. (2016). Social media engagement behaviour: a uses and gratifications perspective. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 24(3), 261-277. http://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2015.1095222

Edelman Trust Barometer (2020). Edelman Trust Barometer 2020: special reports. https://tinyurl.com/3ccpv26x

Emerson, J. & Bugg-Levine, A. (2011). Impact Investing: Transforming How We Make Money While Making a Difference. Jossey-Bass.

Fernández, R. (2024). Ingresos mundiales de Instagram 205-2023. Statista. https://tinyurl.com/yc4mn7m4

Fernández, F. y Martínez, J. (1999). Manual básico de lenguaje y narrativa audiovisual. Paidós.

Ferraz, A. (2000). El lenguaje de la publicidad. Arco.

Field, S. (2001). El manual del guionista. Plot.

Fischer-Appelt, B. & Dernbach, R. (2022): Exploring narrative strategy: the role of narratives in the strategic positioning of organizational change, Innovation. European Journal of Social Science Research, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2022.2062303

Florenthal, B. (2019). Young consumer's motivational drivers of Brand engagement behavior on social media sites. A synthesized U&G and TAM framework. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 13(3), 361-391. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-05-2018-0064

Gaitán, J. A. y Piñuel, J. L. (1995). Metodología general. Conocimiento científico e investigación en la comunicación social. Síntesis.

Gottschall, J. (2013). The storytelling animal. How stories make us human. Mariner Books.

Greimas, A. (1971). Semántica estructural. Investigación metodológica. Gredos.

Grewal, D., Hardesty, D. M. & Iyer, G. R. (2004). The Effects of Buyer Identification and Purchase Timing on Consumers Perceptions of Trust, Price Fairness, and Repurchase intentions. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18, 87-100. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20024

Guber, P. (2007, December). The Four Truths of Storyteller. Harvard Business Review. https://tinyurl.com/34793fym

Havas Group (2019). Meaningful Brands. https://tinyurl.com/2tuxrchj

Hwang, J. & Kandampully, J. (2015). Embracing CSR in pro-social relationship marketing program: Understanding driving forces of positive consumer responses. Journal of Services Marketing 29(5), 344-353. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-04-2014-0118

IAB Spain. (2022). Estudio Anual de Redes sociales. https://tinyurl.com/yveaasc3

Jahn, B. & Kunz, W. (2012). How to transform consumers into fans of your brand. Journal of Service Management, 23(3), 344-361. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231211248444

Katz, E., Blumer, J. & Gurevitch, M. (1973). Uses and Gratifications Research. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(4), 509-523. https://doi.org/10.1086/268109

Kees, J., Berry, C., Burton, S. & Sheehan, K. (2017). An analysis of data quality: Professional panels, student subject pools, and Amazon's Mechanical Turk. Journal of Advertising, 46, 141-155. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1269304

Kim, C., Jin, M. H., Kim, J. & Shin, N. (2012). User perception of the quality, value and utility of user-generated content. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 13(4), 305-320. https://tinyurl.com/mr28ndnj

Krippendorff, K. (1980). Metodología de análisis de contenido. Teoría y práctica. Paidós.

Laurence, D. (2018). Do ads that tell a story always perform better? The role of character identification and character type in storytelling ads. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 35, 283-304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2017.12.009

Li, D. & Atkinson, L. (2020). Effect of emotional victim images in prosocial advertising: the moderating role of helping mode. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 25(4), e1676. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1676

Martínez, F. (4-5 October 2010). La teoría de los usos y gratificaciones aplicada a las redes sociales. II Congreso Internacional Comunicación 3.0, Salamanca, España.

McKee, R. (2009). El Guion. Alba Minus.

Mercé, C. (2014). Brand storytelling. Origins and changes [Final Degree Thesis]. University of Navarra. https://tinyurl.com/29ruzuen

Minto, B. (2009). The pyramid principle. Logic in writing and thinking. Pearon education Limited.

Minton, E. & Cornwell, B. (2015). The Cause Cue Effect: Cause-Related Marketing and Consumer Health Perceptions. Journal of consumer affair, 50(2), 372-402. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12091

Montague, T. (2013). True Story. How to combine story and action to transform your business. Harvard Business Review Press.

Núñez-Gómez, P., García-Guardia, M. y Hermida-Ayala, L. (2012). Tendencias de las relaciones sociales e interpersonales de los nativos digitales y jóvenes en la web 2.0. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (67), 179-206. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-067-952-179-206

Piñuel, J. L. (2002). Epistemología, metodología y técnicas del análisis de contenido. Estudios de sociolingüística 3(1), 1-42.

Porter, E. P. & Kramer, R. M. (2011). Creating Shared Value. How to reinvent capitalism and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review. https://tinyurl.com/sjxeu7wc

Raimondo, M., Cardamone, E., Nino, A. & Bagozzi, R. (2022). Consumer’s identity signaling towards social groups: The effects of dissociative desire on brand prominence preferences. Pyschol Mark, 39, 1964-1978. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21711

Roberts, K. (2005). Lovemarks. The future beyond brands. Empresa Activa.

Rodríguez-Ríos, A. (2024). Del storytelling al storydoing como factor en engagement en redes sociales [Tesis Doctoral]. Universiat Autònoma de Barcelona. https://tinyurl.com/5f3u4smm

Rodríguez-Ríos, A. & Lázaro Pernias, P. (2023). Storydoing as an innovative model of advertising communication that favours an improvement in society. Revisa Latina de Comunicación Social, (81), 171-90. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2023-1865

Sailer, A., Wilfing, H. & Straus, E. (2022). Greenwashing and bluewashing in black Friday-related sustainable fashion marketing on Instagram. Sustainability, 14(3), 1492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031494

Sánchez, R. (2011). Historia e identidades narrativas. Noesis. Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, 20(40), 70-85. https://tinyurl.com/4bza2uaw

Sánchez-Corral, L. (2009). Semiótica de la publicidad: narración y discurso. Síntesis.

Sánchez-Soriano, J. J. y García-Jiménez, L. (2020). La construcción mediática del colectivo LGTB+ en el cine blockbuster de Hollywood. El uso del pinkwashing y el queerbaiting. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (77), 95-116. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2020-1451

Schank, R. & Abelson, R. (1995). Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story. In Rober, S. & Wyer, Jr. (Ed.), Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story (pp. 1-85). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. https://tinyurl.com/tt6u76pu

Selva-Ruiz, D. (2024). Revelando lo silenciado: el poder del storytelling en campañas publicitarias de responsabilidad social. En García García, F. et al. (Coords.), Creatividad en la narrativa publicitaria: estrategia, contenidos y discursos (pp. 107-122). Dykinson. https://doi.org/10.14679/2850

Smith, J. B. & Colgate, M. (2007). Customer value creation: a practical framework. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 15(1), 7-23. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679150101

Spang, K. (2005). Persuasion. Fundamentals of rhetoric. Eunsa.

Tur-Viñes, V. (2015). Engagement, audiencia y ficción. En Rodríguez-Ferrándiz, R. y Tur-Viñes, V. (Coords), Narraciones sin fronteras. Transmedia storytelling en la ficción, la información, el documental y el activismo social y político (pp. 41-59). Cuadernos Artesanos de Comunicación, 81. https://doi.org/10.4185/cac81

Valentini, C. (2018). Digital visual engagement: influencing purchase intentions on Instagram. Journal of Communication Management, 22(4), 362-381. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-01-2018-0005

Vallance, C. (2017, 22 August). Storytelling is dead. Long live storydoing. Campaign. https://tinyurl.com/2kewft3m

Vizcaíno, P. (2016). Del storytelling al storytelling publicitario: el papel de las marcas como contador de historias [Tesis doctoral]. Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. https://tinyurl.com/a9apdzwp

Winsor, J. (2017, 6 December). The end of storytelling. Forbes. https://tinyurl.com/ykzd3nev

Woodruff, R. B. (1997). Customer value: the next source for competitive advantage. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(2), 139-153. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02894350

Woodside, A. & Sood, S. (2016).

Storytelling-Case Archetype Decoding and Assignment Manual (SCADAM). Advances

in Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 11, 15-45.

https://doi.org/10.1108/S1871-317320150000011002

Xu, K. & Wu, Y. (2016). To Tweet or not to Tweet? The Impact of Expressing Sympathy Through Twitter in Crisis Management. PR Journal, 10(2). https://tinyurl.com/3cc9a4tm