index●comunicación

Revista científica de comunicación aplicada

nº 15(01) 2025 | Pages 291-318

e-ISSN: 2174-1859 | ISSN: 2444-3239

The Activity on Instagram Stories of Leaders in The Community of Madrid During Elections

La actividad en las Stories de Instagram de los líderes a la Comunidad de Madrid en elecciones

Received on 21/05/2024 | Accepted on 26/11/2024 | Published on 15/01/2025

https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/15/01Laacti

David Lava Santos | University of Salamanca

djlava12@hotmail.es | https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2352-5083

Abstract: Instagram Stories have become a common political resource in the communicative processes that take place both during and outside electoral campaigns. Political actors rely on the content that can be disseminated in this new digital environment to transmit a direct message to their followers without intermediaries. However, the potential of this new format has yet to be explored at a national level. To shed light on this phenomenon, the main objective of this research is to analyse the digital activity that political leaders in Madrid carried out in the content they disseminated on their Instagram Stories (N=329) during the May 2023 electoral campaign, looking into their agenda of issues and populist discourse.

Keywords: Instagram; Story; Electoral Campaign; Digital Activity; Candidates.

Resumen: El formato Story de Instagram se instaura como un recurso político habitual en los procesos comunicativos que tienen lugar tanto en campaña electoral como fuera de ella. Los actores políticos se apoyan en los contenidos que se pueden difundir en este nuevo entorno digital para transmitir un mensaje directo y sin intermediarios entre sus seguidores. Sin embargo, las potencialidades que ofrece este nuevo formato aún están por explorar a nivel nacional. Para arrojar luz sobre este fenómeno, la presente investigación tiene como objetivo principal analizar la actividad digital que los líderes políticos madrileños han llevado a cabo en el contenido que han difundido en sus Stories (N=329) de Instagram durante la campaña electoral celebrada en mayo de 2023, atendiendo a su agenda de temas y al discurso populista.

Palabras clave: Instagram; story; campaña electoral; actividad digital; candidatos.

To quote this work: Lava Santos, David. (2025). La actividad en las Stories de Instagram de los líderes a la Comunidad de Madrid en elecciones. index.comunicación, 15(01), 291–318. https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/15/01Laacti

1. Introduction

Instagram stands out as the social network with the greatest dynamism in the viral dissemination of political images (López-Rabadán & Doménech-Fabregat, 2019). During campaigns, politicians not only adapt, understand and use social networks, but also seek a strategy that allows them to achieve what is called a 'viral image' (López-Rabadán & Doménech-Fabregat, 2019). Whether stills or moving, images have significant capacity to influence how political speeches are interpreted, as well as their potential to become viral on networks, which makes it easier for candidates' content to reach audiences in a manner that complements the traditional media (López-Rabadán & Doménech-Fabregat, 2019).

The exponential growth in the last decade within all age groups and the visual richness offered by colour-balanced photos and videos (Parmelee & Roman, 2019), make Instagram the platform with the greatest capacity to influence citizens' political behaviours.

In 2016, Instagram created Stories; videos with a maximum duration of 15 seconds that are displayed in the user's profile for just 24 hours. This new format attracts traffic to the creator's profile (Fondevila-Gascón et al., 2020) through likes, comments and the story itself being shared. Over the years, its design has improved, offering the possibility of including preferences such as polls, locations, time of day, etc. in the content, as well as countdowns or links (Fondevila-Gascón et al., 2020).

To date, research analysing the format (Selva-Ruiz & Caro-Castaño, 2017), the agenda of topics or the political discourse (Gamir-Ríos et al., 2022a) on Instagram during campaigns, have focused their efforts on fixed publications, and ignoring the potential impact that Stories format currently afford users of the platform. This may be due to the difficulty involved in compiling this audio-visual element for analysis, as there is a clear theoretical gap on its study in electoral campaigns at a national level.

This research aims to analyse the digital activity followed by the regional candidates represented in the Assembly of the Community of Madrid in their Instagram Stories during the May 2023 campaign. The aim is to verify which interaction resources appeared more frequently, which topics and people set the agenda of the candidates, and if this operability of Instagram allowed the introduction of populist features.

2. Theoretical Framework

To get loyal followers on social networks, academic voices have asserted that political actors must generate quality informative traffic by creating their own content that allows interaction with the users of these platforms (Chaves-Montero & Gadea, 2017). Since the creation of Web 2.0, and until the consolidation of current platforms – albeit with the absence of journalistic intermediaries facilitating the horizontal relationship with internet users (Beriain et al., 2022) – politicians have not taken advantage of interacting in digital environments (Segado-Boj et al., 2016; López-Meri et al., 2020).

As a result, on X (formally Twitter), Spanish politicians do not encourage dialogue with their followers during campaign periods (Alonso-Muñoz et al., 2016). During the 2015 campaign on Facebook, the level of interactivity between politicians and users was zero (Valera-Ordaz et al., 2018). In the specific case of Instagram posts, the use of hashtags is the only interaction resource employed by politicians to "amplify the potential audience of the messages" (Anonymised, 2022a: 163).

The introduction of Stories on Instagram visualises a change in the construction of electoral messaging (Slimovich, 2019; Gil-Torres et al., 2021). The interactive game is no longer reduced to scarce dialogue in the comments of the social network. According to major studies on the central role of reciprocal participation in the digital scenario, the possibility of including hypertext that shows, for example, the specific location during a campaign event; or the ability to offer direct communication thanks to "questions and answers" and sharing content from the account of a third party (Fondevila-Gascón et al., 2020), enables communication where political, citizen and media dynamics are fed back (Fondevila-Gascón et al., 2020).

Internationally, research on the feedback offered by this Instagram service shows that the main form of interaction during campaign periods is politicians diffusing content created by anonymous users of the platform (Slimovich, 2019; Slimovich & García-Beaudoux, 2022). In Spain, research on Stories is still in its infancy, but concludes that certain politicians show greater interactivity with users thanks to the creation of polls (Gil-Torres et al., 2021). To provide new knowledge on the interactive capacity of these time-limited publications, the following research question has been prepared:

RQ1: What interaction resources do leaders in Madrid use in the Stories they disseminate during the campaign?

Thanks to the design implemented on Instagram, Parmelee and Roman (2019) identified the capacity of orientation on aspects of a political nature and the entertainment experience detected by users as the two factors that prompt citizens to follow politicians on the platform. By virtue of this, Instagram posts disseminated by political actors are constructed favouring a spectacularisation strategy (López-Rabadán & Doménech-Fabregat, 2019) of the informative content and "celebrification" of the leader's personal image.

Consequently, the data provided by research analysing the informative agenda on social networks (Alonso-Muñoz, et al., 2016; Larsson & Skogerbo, 2018), underline that politicians almost totally avoid disclosing the specific proposals of their manifesto. On Instagram, the thematic strategy based on mobilising the electorate during campaign periods becomes the central discursive axis of the publications by national leaders (Anonymised, 2022a). For its part, news coverage of public events and the more personal sphere of the candidates intensifies at elections, and does not differ between regional and national candidates (Carrasco-Polaino et al., 2021).

As a result, an "aura of political celebrity" (Caro-Castaño et al., 2020, p. 287) emerges, which consolidates the hegemony of candidates as charismatic electoral guides, and the publications of partisan accounts present party leaders themselves as the main subject (Pineda et al., 2020). The micro-celebrity known as "politician-Instagramer" (Caro-Castaño et al., 2024) appears on Instagram; a candidate who, guided by the actions that govern digital marketing, presents themselves as a star and acts as a media celebrity, while pretending to offer a closer and more family-friendly vision to their followers (Lalancette & Raynaud, 2017).

Although this strategy of humanising the leader occurs through the simulation of a backstage that positions the candidate in informal settings (Selva-Ruiz & Caro-Castaño, 2017), there is no common pattern in the personification in Instagram posts (Selva-Ruiz & Caro-Castaño, 2017). The staging of all forms of personification in Instagram posts does not present a common pattern. Showcasing the candidate network acquires different roles depending on the intended intention. Therefore, among other leadership building strategies, candidates are depicted next to other political members to generate the feeling of "statesmanship" (López-Rabadán & Doménech-Fabregat, 2018, p. 1026); they are surrounded by ordinary citizens (Selva-Ruiz & Caro-Castaño, 2017) and are positioned as mass leaders; or directly, they appear next to the media and are granted the power of "great communicator capable of dialogue" (López-Rabadán & Doménech-Fabregat, 2018, p. 1026).

Following the above review, we pose the following research questions:

RQ2: What topics set the agenda of candidates in Stories?

RQ3: Who are the stars of the Stories? What attitude and attribute do political leaders acquire on Instagram?

The embodied communication from informal and everyday life scenarios generates an image of politicians that are "accessible, transparent and appreciative of [their] community of followers" (Caro-Castaño et al., 2024). In the digital era, the creation of online communities, coupled with historical factors and social crises, is prone to the implementation of populist discourses (Waisbord, 2020). The communicative dynamics of these networks allow politicians to present themselves as authentic and common people; one more part of those rejecting the elites (Mudde, 2004), and, through the introduction of sensationalist language (Alonso-Muñoz & Casero-Ripollés, 2021), they interpellate an elector-ate that lacks a group identity (Gerbaudo, 2023).

Despite the academic debate on its conceptualisation, populism is considered a form of negative discourse (Jagers & Walgrave, 2007) that separates the political community into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups (Mudde, 2004); the pure people versus the corrupt elite. Its essence is gradual (Jagers & Walgrave, 2007; Anonymised, 2023), which favours all actors on the ideological axis to use its stylistic and discursive advantages. Social research shows that, on X or Facebook, politicians with more public experience present an "empty populism" (Jagers & Walgrave, 2007) focused on defending people, while those considered populist essentially allude to a "full populism" (Ernst et al., 2017; Engesser et al., 2017) of questioning power structures.

In the Spanish case on Instagram, Rooduijn et al. (2023) identify a strategy focused on discrediting elites in the posts by VOX leader Santiago Abascal. However, Pablo Casado or Pedro Sánchez, on the same social network, exclusively used the narrative of appealing to people under a highly emotive style as a populist strategy (Anonymous, 2023). To test the populist traits of the Stories, the following research question is proposed:

RQ4: Are traits of populist message noticeable in the Stories disseminated by the candidates? What are those traits according to the candidate issuing the populist content?

3. Methodology

3.1. Method, Corpus and Time Frame

With the intention of analysing the digital activity that Madrid's political leaders have carried out in the content they have disseminated via their Instagram accounts, the research methodology presents a dual quantitative-qualitative approach applying the classical content analysis as a study tool (Krippendorff, 2004) to a sample made up of the 329 Stories published by the leaders of the parties that were represented in the Assembly of the Community of Madrid following the May 2023 electoral campaign. The political candidates investigated are Isabel Díaz Ayuso (PP); Juan Lobato Gandarias (PSOE); Mónica García Gómez (Más Madrid) and Rocío Monasterio San Martín (VOX).

The materials were collected manually from 12 May to 26 May 2023, between 11:45 pm and 11:59 pm daily. The Stories of the leaders were captured from their official accounts using the screen recorder of the mobile device of the signatory of the work. This allowed a textual and multimedia analysis of the content. Recording at this time ensures a full daily compilation in Excel before the platform automatically deletes the content after 24 hours.

Table 1. Research Corpus

|

Instagram Account |

No. of Stories |

|

@isabeldiazayuso |

2 |

|

@juanlobato_es |

58 |

|

@monicagarciag |

180 |

|

@rociomonasteriovox |

89 |

|

Total |

329 |

Source: Author's own.

The research covers a 15-day period of the Madrid campaign. The diversity of previous studies (Anonymised, 2023) supports the suitability of studying digital political activity during the official days of the campaign, when political coverage on social networks intensifies.

3.2. Research Design and Variables

To answer the research questions posed, a coding sheet was developed identifying a total of eight variables, whose purpose was to classify the study of the subcategories related to interactivity, the agenda of issues in the campaign, the stars and their attributes, and populism in Instagram Stories. The significant lack of research on Stories in political communications resulted in the categorisation of the variables being carried out through a mixed deductive and inductive procedure. In the design of the subcategories where the themes, stars, attributes and populism of the publication were analysed, parameters used by previous works on the political use of this social network were taken as a reference; while, in the subcategory aimed at investigating interactivity, the coding was carried out through the creation of variables based on the academic experience (Olano et al., 2020) of the researcher.

Simultaneously, a study subcategory was established that – using the "content creator" variable (v1) – indicated who generated the original content of the Story. When a third user tags the digital identifier of the politician in their publication, that candidate can share it in their own Story, reaching the entire community. This practice allows us to measure the degree of interaction with other users of the platform (RQ1), and to verify whether candidates amplify their original discourse and rely on the political message produced by other social agents (Segado-Boj et al., 2016; Marcos-García et al., 2021) present in the digital environment.

To answer RQ1 on interaction resources, the "content creator" variable, generated ad hoc for the research, distinguished whether the publication was its own (generated by the leader) or external (produced by a third user). Using the visual indicator "tags" at the top left of the Story, content shared by the politician from another account was categorised as extraneous. In the case of the interactivity subcategory, the "interaction elements" variable (v2) is based on the classification of previous works (Lalancette & Raynaud, 2017; Anonymised, 2022a), and analysed whether the publication generated by the politician contained interactive resources or not, or, on the contrary, the interaction mechanisms (see Table 2) that the Story allows (Fondevila-Gascón et al., 2020). Within its coding, the presence of interaction resources present in the Stories considered to be unrelated was not measured due to the difficulty involved in visually recognising this material, since Instagram does not allow distinguishing inter-active material in shared stories.

To analyse the themes present in the message of the Stories (RQ2), we used the "agenda of topics" variable (v3), where, as in previous studies (López-García, 2016; Anonymised, 2024), we operated with the four macro-categories proposed by Mazzoleni (2010) for the analysis of the themes present in the political content of social networks. In this sense, own and third-party publications were coded according to whether the topic was related to the categories "political issues"; aspects linked to ideological issues and electoral confrontation; "campaign issues"; issues related to the strategies and organisation of the campaign; "policy issues" when the issues shown referred to sectorial political issues and, finally, "personal issues"; when the content of the Story reflected personal issues of the candidate.

Table 2. Study Variables

|

Subcategory |

Variable |

Categorisation |

|

Content |

Content creator |

1. Own 2. Third-party |

|

Interactivity |

Interaction Elements |

1. Hashtags 2. Countdown 3. Mentions 4. Web links 5. Web links and mentions 6. Web links and Hashtags 7. Polls 8. Emojis with reactions 9. Your turn 10. Q&A 11. Location 12. Location and link 13. Location and Hashtags 14. Location and mentions 15. Other |

|

Theme |

Agenda setting |

1. Political issues 2. Campaign issues 3. Personal issues 4. Policy issues |

|

Protagonism |

Star of Action |

0. Not applicable 1. User alone 2. User accompanied by: institutional representatives/public figures/politicians from other parties/journalists/party colleagues or collaborators/family or friends/anonymous militants or supporters/anonymous citizens 3. The user does not appear, but: institutional representatives/public figures/politicians from other parties/journalists/party colleagues or collaborators/family or friends/anonymous militants or supporters/anonymous citizens 4. Others

|

|

Candidate's Attitude |

1. Formal 2. Informal |

|

|

Role |

1. Statesperson 2. Good manager 3. Great communicator 4. Mass leader 5. Hero 6. Committed 7. Approachable 8. Cultured 9. Athlete 10. Mother/Father, husband/wife or friend 11. Devout |

|

|

Populism |

Populist Discourse |

1. Appeal to the people 2. Criticism of elites 3. Defending popular sovereignty 4. Appeal to cultural traits 5. Ostracism of others |

|

Populist Style |

1. Emotional 2. Simplistic 3. Negative |

Source: Author's own based on the methodology of Lalancette & Raynaud (2017); Anonymised (2022a); Mazzoleni (2010); Quevedo-Redondo & Portalés-Oliva (2017); Selva-Ruiz & Caro-Castaño (2017); López-Rabadán & Doménech-Fabregat (2019); Ernst et al. (2017) and Engesser et al. (2017).

The "star of the action" (v4), "candidate's attitude" (v5), and "role" (v6) variables were used to identify the star (RQ4) of the posts and the role assumed by the political leader as the main subject in a given context. The construction and categorisation of these variables were inspired by the work of Zamora-Martínez et al. (2020) on the study of stars and their roles in Instagram posts by national political candidates. Their research, in turn, draws methodological information from studies on political behaviours – also on Instagram – conducted by Quevedo-Redondo & Portalés-Oliva (2017), Selva-Ruiz & Caro-Castaño (2017), and López-Rabadán & Doménech-Fabregat (2019).

Finally, the variables in the subcategory of populist messages (RQ4) follow the methodology proposed by Ernst et al. (2017) and Engesser et al. (2017), which define the construction of populism on the network through a discursive and stylistic approach. Under the framework of studies on populism on Instagram (Anonymised, 2023; Rooduijn et al., 2023), the content of all Stories was coded dichotomously, determining whether the message included discourse (v7) that: "appealed to the people" as a common cultural group; "criticised the elites" as antagonists and enemies of the people; "defended popular sovereignty" and their right to decide; "appealed to cultural traits" of national identity; and finally, "ostracised social groups" considered harmful to people's well-being. Regarding the populist style (v8), it was recorded whether the message contained "emotional", "simplistic" short-term policies (Alonso-Muñoz & Casero-Ripollés, 2021), or "negative" appeals to social, political, or economic crises.

4. Results

Analysing the digital activity of each candidate separately allows us to obtain a more detailed view of the strategies followed during this election period, which, in turn, facilitates the possibility of identifying behavioural patterns in the Stories that may not be evident if analysed jointly. For this reason, the data obtained are presented both in an integrated manner, taking into account the percentage of each variable with respect to the total of the material, and broken down by candidate.

4.1. Interactivity of the Stories

A preliminary assessment reveals a notable disparity in the digital activity of political candidates in Stories. The leaders of the traditional parties, Isabel Díaz Ayuso for the PP of Madrid (1.82%), and the PSOE candidate, Juan Lobato (17.62%), obtained an anecdotal percentage in comparison with the total number of publications collected. On the other hand, the candidates of the newest parties, Mónica García of Más Madrid (54.71%) and Rocío Monasterio of VOX (27.05%), found a new temporary space in this format in which to be active during the campaign, with a total of 180 and 80 Stories, respectively.

Table 3. Percentage distribution of own and third-party Stories broken down by candidate

|

Candidates |

Total Stories |

Own Stories |

Third-party Stories |

|||

|

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

Isabel Díaz Ayuso |

2 |

1.82% |

2 |

100% |

0 |

/ |

|

Juan Lobato |

58 |

17.62% |

38 |

65.51% |

20 |

34.48% |

|

Mónica García |

180 |

54.71% |

82 |

45.55% |

98 |

54.44% |

|

Rocío Monasterio |

89 |

27.05% |

9 |

10.11% |

80 |

89.88% |

|

Total |

329 |

100% |

131 |

39.81% |

198 |

60.18% |

Source: Author's own.

The percentages represented in Table 3 reflect a clear interactive connection of the political leaders with the virtual community of Instagram (RQ1) and, in general terms, it can be seen that the candidates disseminated a large amount of content generated by third parties. The sharing of other people's publications (v1) exceeds 60% of the total material collected. However, if we look at the data segregated by candidate, we see that Isabel Díaz Ayuso, in 100% of her publications, and Juan Lobato in 65.51% (38), disseminated their own content without resorting to this interactive function of Instagram. On the other hand, Mónica García (54.44%) and Rocío Monasterio (89.88%) relied more frequently on social actors to broadcast their political message to their followers.

Table 4. Interactive resources in own Stories

|

Interactive Resource |

N |

|

Hashtag |

1 |

|

Mentions |

12 |

|

Hashtag and mentions |

2 |

|

Web link |

17 |

|

Emoji and Reaction |

1 |

|

Your turn |

1 |

|

Location |

8 |

|

Location and link |

2 |

|

Location and hashtag |

3 |

|

Q&A |

1 |

|

Other |

2 |

|

Total |

50 |

Source: Author's own.

Table 4 shows the total percentage of interactive resources used in the candidates' original Stories. Fifty (38.16%) of the 131 own publications during the campaign contained the presence of integrated interactive elements. In addition, when these accompanying tools were used, the mention of other users (24%), the presence of hyperlinks with web links (35%), and the sharing of geolocated location (16%) emerged as the predominant interactivity strategies. On the other hand, highly dynamic elements such as emojis with reaction (2%), Q&As (4%) or the individual use of hashtags (2%) were barely seen.

By candidate, Rocío Monasterio did not include participatory tools in her nine Stories, whereas Isabel Díaz Ayuso used locations and mentions to interact with her followers. For Mónica García and Juan Lobato, the percentages show that these were the two candidates who resorted most to using interactive resources. In fact, 41.46% of the Más Madrid candidate's Stories contained mentions or external links, while 31.5% of Juan Lobato's content was interactive.

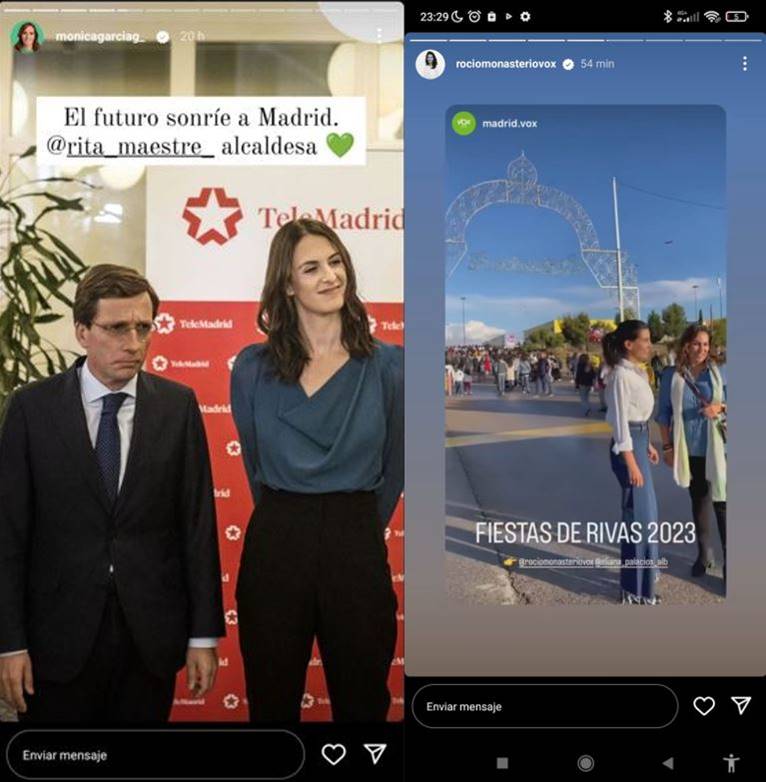

Figure 1. On the left, an example of a personal Story with a mention. On the right, an example of someone else's Story

Source: Instagram screenshot of Mónica García and Rocío Monasterio.

4.2. Themes and Stars in the Stories

The joint analysis of the candidates' Stories reveals that the thematic macro-category (RQ2) related to campaign developments had a significant presence in the overall political information shared. The multimodal analysis demonstrated that in 72.94% of the Stories, the main intention was to inform users about the location and timing of various campaign events and rallies, while clearly encouraging electoral participation. Additionally, a significant number of Stories reflected the support expressed by anonymous citizens through the dissemination of external content. These Stories highlighted individuals participating in electoral events and exercising their right to vote in favour of the candidates. Some Stories even included images and videos displaying the party's own electoral ballots.

Simultaneously, the Stories also addressed sectoral political issues. In this regard, topics such as healthcare, education, and the economy represented 14.89% of the total Stories. Personal matters barely reached 10%, indicating that candidates rarely drew on their private lives. When they do, family members are absent, and posts tend to focus on personal preferences instead. Lastly, political issues of confrontation, such as partisan disputes or potential government coalitions, were minimal, with only 10 of the 329 contents addressing such topics.

Table 5. Main themes of the Stories

|

Category |

N |

% |

|

Campaign issues |

240 |

72.94% |

|

Political issues |

10 |

3.03% |

|

Policy issues |

49 |

14.89% |

|

Personal issues |

30 |

9.11% |

|

Total |

329 |

100% |

Source: Author's own.

Regarding the main theme of the Stories based on the candidate disseminating the message, the data reveal a uniform trend with the predominant focus on campaign-related issues. Consequently, the percentages segmented by leader show a clear similarity with the data representing the overall Stories. In more than 70% of the posts by Mónica García, Rocío Monasterio, and Juan Lobato, the category referred to as campaign issues predominated. Sectoral issues achieved percentages exceeding 10% and 20%, while personal matters and political confrontations recorded residual percentages. An exception is Isabel Díaz Ayuso where 100% of her Stories highlighted her personal side, appearing in a restaurant. The other candidates aimed to convey a message about the campaign's progress and, to a lesser extent, focused on disseminating topics of public interest.

Table 6. Main themes of the Stories by candidate

|

Theme/ Candidate |

Campaign |

Political |

Policy |

Personal |

|

Mónica García |

129 |

8 |

24 |

19 |

|

Rocío Monasterio |

69 |

1 |

12 |

7 |

|

Juan Lobato |

42 |

1 |

13 |

2 |

|

Isabel Díaz Ayuso |

/ |

/ |

/ |

2 |

Source: Author's own.

Regarding RQ3, in more than half of the cases, the candidates appeared accompanied by other social agents (67.17%), compared to 16.10% of Stories where the politician was the main subject of the action without any other person present. In most posts, the candidates could be seen in the company of party members and supporters (33.48%) or backed by politicians from their own party (25.79%). Additionally, in 17.19% of the Stories where the candidate appeared accompanied, anonymous citizens played a prominent role during the limited timeframe.

It seems logical to assume that, in line with the trend showing that the main theme of the Stories was driven by the campaign's evolution, candidates shared content featuring third-party users or themselves alongside journalists and media outlets on 26 occasions during electoral debates or interviews. Moreover, it is noteworthy that even when the Stories did not highlight the party's candidate as the main subject, it was often party supporters (30.76%), and particularly anonymous citizens (35.89%), who played the leading role in the action.

The data collected for each candidate do not challenge the general trend reflected by the Stories overall. Excluding the PP leader, the profiles of Mónica García, Rocío Monasterio, and Juan Lobato aimed to give clear prominence to anonymous citizens and members of their respective parties. For instance, the Más Madrid candidate was surrounded by her supporters in 41 instances, and Mónica García appeared alongside anonymous citizens in 14 Stories. Monasterio was shown surrounded by her party members in 23.59% of her Stories and close to anonymous citizens in 22.47% of her content.

Table 7. Main star of the Story's content

|

Star |

% |

|

Not applicable |

4.86% |

|

Politician alone |

16.10% |

|

Politician accompanied |

67.17% |

|

Cultural figures |

1.35% |

|

Politicians from another party |

8.59% |

|

Journalists |

11.76% |

|

Politicians from own party |

25.79% |

|

Family members |

0.45% |

|

Party members |

33.48% |

|

Anonymous citizens |

17.19% |

|

Animals |

1.35% |

|

Politicians does not appear, but… |

11.85% |

|

Cultural figures do |

5.12% |

|

Politicians from another party do |

5.12% |

|

Politicians from own party do |

17.94% |

|

Party members do |

30.76% |

|

Anonymous citizens do |

35.89% |

|

Others |

5.12% |

Source: Author's own.

Of the 274 Stories where the candidate was the main focus, either alone or surrounded by other social agents, the formal attitude (v5) of the candidate predominated, accounting for 67% (n=184), significantly surpassing the informal attitude, which represented the remaining 33% (n=90). Qualitative analysis confirmed the presence of a protocol-like and regulated behaviour in 104 Stories by Mónica García and 33 by Juan Lobato. Only 40 Stories from the Más Madrid candidate and 14 from the PSOE leader displayed an informal behaviour. Rocío Monasterio also presented a higher percentage of content where her image was associated with correct political conduct (58% of the total Stories where she appeared as the main subject). However, the profile of VOX's leader in Madrid showed a significant informal presence, appearing in 42% of her Stories.

Figure 2. Story by Mónica García with an informal tone. Story by Juan Lobato with a formal tone.

Source: Instagram screenshots of Mónica García and Juan Lobato.

Finally, regarding the attribute displayed by the candidate in the Stories (v6), a dichotomy was observed in the representation of the account user under a dual role: on one hand, as an "ordinary and approachable person" (n=88), and on the other, as an "individual prepared with a vision for the future" (n=76). Both the Stories shared from third-party accounts and those originally disseminated by the leader of the political group were based on the representation of the candidate alongside other supporters and ordinary people. This contributed to constructing the leader's image as a relatable citizen. Additionally, the support expressed by the candidates through the sharing of other users' posts positioned them as suitable candidates for the presidency of the Community. Stories also highlighted attributes such as "great communicator" (n=38) and "mass leader" (n=37), while the categories of "hero" (n=3) or "experienced candidate" (n=1) were barely seen.

4.3. Presence of Populism in the Stories

Of the total Stories analysed (N=329), more than half, 175 (53.19%), contained at least one characteristic of strategies related to populist discourse or style (RQ4). In this sense, defending the people as a common cultural group became the most used discursive resource across the Stories with 20.06% of the total messages. In contrast, the rejection of elites and defending popular sovereignty did not play a significant role in the discursive approach of the campaign Stories; they were only used sparingly, in 1.83% and 0.91% of cases, respectively.

Another aspect highlighted by the percentages in the research is the almost common use of emotionality as a populist stylistic symbol. While the use of messages alluding to an unfavourable social context for the people (5.41%) or announcing short-term and simplistic policies (8.20%) had little representation, the construction of an audiovisual narrative laden with sensationalist messages emerged as the quintessential populist stylistic approach in Stories during the campaign, at 53.19% of the publications.

Regarding the discrepancies in populist messaging by candidate, it can be stated that Rocío Monasterio is the only leader who employed all the characteristics of this political phenomenon in her Stories. While the presence of discourse advocating the people's authority to decide their future was scarce across the material, Monasterio dominated this aspect. Rocío Monasterio is also the only candidate who allowed the circulation of Stories, both her own and others', aimed at marginalising social groups such as immigrants (16.85%). Furthermore, she was the leader who most exalted cultural and historical traits (32.58%), using symbols such as the Spanish flag in her publications.

In the case of Isabel Díaz Ayuso, none of the two Stories she shared in May contained populist elements, either discursive or stylistic. Similarly, Juan Lobato did not reach a high degree of populism. When he appealed to the people, the percentage did not exceed 20%. On the other hand, the Más Madrid candidate demonstrated a stronger defence of ordinary people (n=34), addressing them as "the people of Madrid," as shown by the qualitative analysis of the Stories. Additionally, she criticized the elites in one message and appealed to Madrid's cultural and identity values on five occasions.

Emotionality was present in 43.10% of Juan Lobato's Stories, in more than 50% of Mónica García's, and in 65.16% of Rocío Monasterio's. Negativity barely featured in the messaging of the PSOE leader or the Más Madrid candidate; only two Stories by Juan Lobato and three by Mónica García adopted this populist style. Rocío Monasterio employed a more negative tone, attempting to show users on 13 occasions the "social crisis" that the "people of Madrid" were experiencing. Finally, the communicative approach based on simplistic messages was only present in the Stories of Mónica García and Rocío Monasterio, with the latter showing the highest percentage of simplistic messages.

Table 8. Candidate in the message of the Stories

|

Candidate/ Populist Trait |

Juan Lobato |

Mónica García |

Rocío Monasterio |

|||

|

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

Appeal to the People |

13 |

22.41% |

34 |

18.90% |

19 |

21.34% |

|

Criticism of the elites |

/ |

/ |

1 |

0.55% |

6 |

6.74% |

|

Defending popular sovereignty |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

3 |

3.37% |

|

Appeal to cultural traits |

/ |

/ |

5 |

2.77% |

29 |

32.58% |

|

Ostracism of others |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

15 |

16.85% |

|

Emotionality |

25 |

43.10% |

92 |

51.12% |

58 |

65.16% |

|

Negativity |

2 |

3.45% |

3 |

1.66% |

13 |

14.60% |

|

Simplistic |

/ |

/ |

9 |

5% |

18 |

20.22% |

Source: Author's own.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

During the process of gathering literature on the subject, only three studies (Slimovich, 2019; Slimovich & García-Beaudoux, 2022; Gil-Torres et al., 2021) were found related to the analysis of political activity in the Stories of various candidates – one Spanish and two focusing on elections in Argentina. Moreover, in the national case study, the Stories of Pedro Sánchez and Pablo Iglesias shared during 2019 and 2020 were not considered as units of analysis in themselves but rather as an integral part of Instagram's Feedback (Gil-Torres et al., 2021). Therefore, given the notable lack of data in this field of study, much of the discussions raised in the article are not supported in previous research. Where comparisons were possible, the data were aligned with studies that, in recent years, have addressed the political use of Instagram's primary format: posts.

After analysing the publication frequency of Stories by Madrid's candidates (N=329), we can affirm that this visually appealing communication format is consolidating itself in the national political landscape as yet another medium for conveying messages during electoral campaigns. Instagram Stories represent a new digital reality that, along with Instagram posts and publications on Facebook and X, deserve academic analysis to understand their political, civil, and media impact.

Of course, as López-Olano et al. (2020) pointed out, it is difficult to understand the reasons that lead political candidates to generate informational traffic on social networks, and in the specific case of Instagram Stories, this situation persists. Isabel Díaz Ayuso, who has a total of 719,000 followers on Instagram and was the president of the Community of Madrid prior to the election, stood out for sharing only two Stories during the period analysed. Her direct opponent, Juan Lobato, with 13,000 followers on the platform, also did not pursue an active political strategy through Stories. Mónica García (103,000 followers) and Rocío Monasterio (195,000 followers) were the most dynamic candidates.

Selva-Ruiz & Caro-Castaño (2017) and López García (2016) identified the parties and candidates of the "new politics" as the most active on social networks. Subsequent studies (Anonymised, 2022b) demonstrated that this difference diminished, and in 2019, the PP and PSOE were more active than Podemos or Ciudadanos on X and Instagram. Focused on the Madrid campaign, the "traditional parties" still show some restraint in leveraging the advantages offered by Instagram's new format. Meanwhile, candidates from parties with less presence in public life, as observed in the activity of Instagram posts during various regional campaigns (Carrasco-Polaino et al., 2020; López-Olano et al., 2020), display a more consistent posting pace.

In response to RQ1, Stories offer new avenues of interaction not previously categorised in political communications. According to studies on Instagram interactivity (Lalancette & Raynaud, 2017; Sampietro & Sánchez-Castillo, 2020), hashtags and mentions became the two "go-to" resources (Anonymised, 2022a) used by politicians. However, the fact that more than half of the Stories in this campaign were shared from an external account shows that this format allows for more direct and spontaneous interaction (Slimovich, 2019), where followers feel addressed and can see that their message was viewed and shared by the candidate.

In the 131 Stories that originated from the politicians, the use of interactive resources such as geolocation, hashtags, mentions, or Q&As is present in only 50 posts. This aligns with research suggesting that interaction on social networks by politicians is limited (López-Meri et al., 2020; Marcos-García et al., 2021). In this sense, although we can observe a higher degree of interactivity in the candidates' Stories, their primary level of engagement remains relatively passive, and they do not fully exploit all the advantages of digital participation.

The study of political topics (RQ2) seems to indicate the existence of a common logic in the Instagram Stories of the candidates. The contents that garnered the highest percentages focused on campaign public events and supporter endorsements. In line with studies that have analysed the main themes of fixed Instagram posts (Pineda et al., 2020; Anonymised, 2022a), we can affirm the continuity of this format as a medium for disseminating issues related to the progression of the campaign.

Additionally, when comparing the percentages of Stories from the Community of Madrid with the findings of international research on the themes addressed in this format (Slimovich, 2019; Slimovich and García-Beaudoux, 2022), a similar trend in the discursive use of this tool is evident. Indeed, if Madrid candidates used Stories as an audiovisual campaign album, in Argentina, references to electoral events and participation in media interviews also played a prominent role in the digital activity of candidates on Instagram.

In contrast, our study has highlighted a novel discursive inclination. At a national level, the presence of ideological issues and ideological confrontations has acquired significant and increasingly higher percentages in the Instagram agenda of candidates (Anonymised, 2022a). However, in the Stories of the leaders from this autonomous community, political issues have barely appeared, while sectoral issues rank second. From this research, we can affirm that the flexible nature of Stories, which allows them to be free from format and content limitations, can be an advantage in exploring themes related to the specific proposals of political programmes.

Looking at RQ3, the analysis of the star in the Stories supports a process of hyper-leadership (Egea-Barquero & Zamora-Medina, 2022) through a strategy that focuses political content on the main party candidate, whether alone or accompanied by other social actors. Regarding the staging of this personalisation, politicians have not portrayed themselves in Stories as family-oriented individuals. Unlike in other countries, the audiovisual culture in Spain presents politicians as more discreet when sharing images of their personal or family lives (Egea-Barquero & Zamora-Medina, 2022). The informal disposition of candidates on Instagram seems to be related to their goal of presenting themselves as political figures close to citizens.

The strategy of personalising Spanish politicians on Instagram presents a dichotomy between the construction of statespersonlike and populist attributes (Zamora-Martínez et al., 2020). In line with this, Stories reinforce this practice. By framing the candidate accompanied by their supporters and anonymous citizens while repeatedly adopting a formal attitude, this allows for the projection of a dual image of the political leader: that of an ordinary individual close to the people and that of a qualified professional prepared to assume leadership.

Finally, we can position Instagram Stories as a format that may facilitate the introduction of populist traits into the messages of political candidates during campaigns (RQ4). However, the use of populist discourse and style is conditioned by the political actor disseminating the Story. As noted by Jagers & Walgrave (2007) and confirmed by subsequent studies on this phenomenon on social networks (Ernst et al., 2017; Engesser et al., 2017; Anonymised, 2023; Anonymised, 2024), leaders of traditional parties tend to use "empty populism" focused on appealing to and defending the people as the central discursive axis. On the other hand, political actors with less experience in public life feed their content with "complete populism", where criticism of groups and members of supranational organisations becomes a common resource on social networks. In line with both approaches, it is shown that the two candidates from parties with less history in national politics achieved a higher level of populism in their discourse, while Lobato either does not include populist elements in his messages or, when he does, directly appeals to the people as the "people of Madrid".

The main limitation of this research lies in the lack of extensive studies on the digital use of Instagram Stories, which has restricted our conclusions. To address this issue, it is suggested that future research analyse digital activity in Stories during a general election. This would afford a comparison between national and regional politics, opening new avenues for analysis in this social communications medium.

It is important to note that, although the results provide a significant insight into the digital activity of the Madrid candidates on Instagram Stories, there was a limitation related to the small number of publications by the PP candidate, Isabel Díaz Ayuso, who, as mentioned throughout the study, only shared two Stories. This low volume of content limits the representativeness of her results and their comparability with other candidates, so any extrapolation must be interpreted with caution.

Ethics and Transparency

Acknowledgements

To Liza D`Arcy for the translation of the work and to the University of Salamanca.

Conflict of Interest

This research presents no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research has not received funding.

Author Contributions

|

Contribution |

Author 1 |

Author 2 |

Author 3 |

Author 4 |

|

Conceptualization |

X |

|

|

|

|

Data curation |

X |

|

|

|

|

Formal Analysis |

X |

|

|

|

|

Funding acquisition |

X |

|

|

|

|

Investigation |

X |

|

|

|

|

Methodology |

X |

|

|

|

|

Project administration |

X |

|

|

|

|

Resources |

X |

|

|

|

|

Software |

X |

|

|

|

|

Supervision |

X |

|

|

|

|

Validation |

X |

|

|

|

|

Visualization |

X |

|

|

|

|

Writing – original draft |

X |

|

|

|

|

Writing – review & editing |

X |

|

|

|

Data Availability Statement

There is a possibility of accessing the data through the authors.

References

Alonso-Muñoz, L., Miquel-Segarra, S. & Casero-Ripollés, A. (2016). Un potencial comunicativo desaprovechado. Twitter como mecanismo generador de diálogo en campaña electoral. Obra digital: revista de comunicación, (11). https://bit.ly/4c3XTUz

Alonso-Muñoz, L. & Casero-Ripollés, A. (2021). ¿Buscando al culpable? La estrategia discursiva en Twitter de los actores políticos populistas europeos en tiempos de crisis. Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación, 26, 29-45. https://doi.org/10.6035/clr.5827

Beriain Bañares, A., Crisóstomo Gálvez, R. & Chiva Molina, I. P. (2022). Comunicación política en España: representación e impacto en redes sociales de los partidos en campaña. Revista mexicana de ciencias políticas y sociales, 67(244), 335-362. https://doi.org/10.22201/fcpys.2448492xe.2022.244.75881

Bossetta, M. (2018). The digital architectures of social media: Comparing political campaigning on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat in the 2016 US election. Journalism & mass communication quarterly, 95(2), 471-496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699018763307

Caro-Castaño, L., Dueñas, P. P. M. & Osorio, J. G. (2024). La narrativa del político-influencer y su fandom: El caso de Isabel Díaz Ayuso y los ayusers en Instagram. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación: Mediterranean Journal of Communication, 15(1), 285-303. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM.25339

Carrasco Polaino, R., Sánchez de la Nieta, M. Á. & Trelles Villanueva, A. (2021). Análisis de la comunicación en Twitter durante la cobertura de la explosión de la calle Toledo de Madrid: Polaridad, objetividad y engagement. Dykinson.

Chaves-Montero, A., Gadea-Aiello, W. F & Aguaded-Gómez, J. I. (2017). La comunicación política en las redes sociales durante la campaña electoral de 2015 en España: uso, efectividad y alcance. Perspectivas De La Comunicación, 10(1), 55–83. https://bit.ly/4coGsOA

Díaz, J. B. & del Olmo, F. (2021). Presencia e interacción de los candidatos a la presidencia del Gobierno de España en las principales redes sociales durante la campaña electoral de noviembre de 2019. OBETS: Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 16(1), 63-74. https://doi.org/10.14198/OBETS2021.16.1.04

Egea-Barquero, M. & Medina, R. Z. (2023). La personalización política como estrategia digital: análisis de los marcos visuales que definen el liderazgo político de Isabel Díaz Ayuso en Instagram. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 29(3), 567. https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/esmp.84824

Engesser, S., Fawzi, N. & Larsson, A. O. (2017). Populist online communication: Introduction to the special issue. Information, communication & society, 20(9), 1279-1292. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328525

Ernst, N., Engesser, S. & Esser, F. (2017). Bipolar populism? The use of anti-elitism and people-centrism by Swiss parties on social media. Swiss political science review, 23(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12264

Fondevila Gascón, J. F, Gutiérrez Aragón, Ó., Copeiro, M., Villalba Palacín, V. & Polo López, M. (2020). Influencia de las historias de Instagram en la atención y emoción según el género. Comunicar: revista científica iberoamericana de comunicación y educación, 63, 51-50. https://doi.org/10.3916/C63-2020-04

Gamir-Ríos, J., Cano-Orón, L., Fenoll, B. & Iranzo-Cabrera, M. (2022). Evolución de la comunicación política digital (2011–2019) ocaso de los blogs, declive de Facebook, generalización de Twitter y popularización de Instagram. Observatorio (OBS*), 16(1), 90-115. https://bit.ly/4cokSJT

Gamir-Ríos, J., Cano-Orón, L. & Lava-Santos, D. (2023). De la localización a la movilización. Evolución del uso electoral de Instagram en España de 2015 a 2019. Revista de comunicación, 21(1), 159-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.26441/rc21.1-2022-a8

Gerbaudo, P. (2023). O grande recuo: A política pós-populismo e pós-pandemia. Todavia.

Gil Torres, A., Tapia Cuesta, S. & San José de la Rosa, M. C. (2021). Política y redes sociales. Perfiles de Pedro Sánchez y Pablo Iglesias en Instagram antes y después de ser cargos públicos (2019-2020). Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 12(2), 177-193.https://doi.org/10.14198/medcom.18141

Jagers, J. & Walgrave, S. (2007). Populism as political communication style: An empirical study of political parties' discourse in Belgium. European journal of political research, 46(3), 319-345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x

Lalancette, M., & Raynauld, V. (2019). The power of political image: Justin Trudeau, Instagram, and celebrity politics. American behavioral scientist, 63(7), 888-924. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764217744838

Larsson, A. & Skogerbø, E. (2018). ¿Fuera lo viejo, dentro lo nuevo? Percepciones de los medios sociales (y otros) por parte de los políticos noruegos locales y regionales. Nuevos medios y sociedad, 20 (1), 219-236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816661549

Lava-Santos, D. & Ibáñez-Cuquerella, M. (2023). Temática y negatividad de la clase política en Twitter durante las elecciones autonómicas de Castilla y León de 2022. Fonseca, Journal of Communication, 27, 170-191. https://doi.org/10.48047/fjc.27.01.11

López-García, G. (2016). ‘Nuevos’ y ‘viejos’ liderazgos: la campaña de las elecciones generales españolas de 2015 en Twitter. Communication & society, 29(3), 149-168. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.29.35829

López-Meri, A., Marcos-García, S. & Casero-Ripollés, A. (2020). Estrategias comunicativas en Facebook: personalización y construcción de comunidad en las elecciones de 2016 en España. Doxa Comunicación, 30, 229-248. https://doi.org/10.31921/doxacom.n30a12

López-Rabadán, P. & Doménech-Fabregat, H. (2018). Instagram y la espectacularización de las crisis políticas. Las 5W de la imagen digital en el proceso independentista de Cataluña. El profesional de la información, 27(5), 1013-1029. http://hdl.handle.net/10760/39281

López Rabadán, P. & Doménech-Fabregat, H. (2019). Gestión estratégica de Instagram en los partidos españoles. El avance de la política espectáculo en el proceso independentista de Cataluña. Trípodos, 45, 179-207. http://hdl.handle.net/10234/187017

López-Rabadán, P. & Doménech-Fabregat, H. (2021). Nuevas funciones de Instagram en el avance de la “política espectáculo”: Claves profesionales y estrategia visual de Vox en su despegue electoral. El profesional de la Información, 30(2), e300220. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2021.mar.20

Marcos-García, S., Alonso-Muñoz, L. & López-Meri, A. (2021). Campañas electorales y Twitter. La difusión de contenidos mediáticos en el entorno digital. Cuadernos. información, (48), 27-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.7764/cdi.48.1738

Mazzoleni, G. (2010). La comunicación política. Alianza Editorial.

Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and opposition, 39(4), 541-563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

Olano, C. L., Castillo, S. S. & Pérez, B. M. (2020). L’ús del vídeo en les xarxes socials dels candidats a la Generalitat Valenciana 2019. Debats. Revista de cultura, poder i societat, 134(1), 117-132. https://doi.org/10.28939/iam.debats.134-1.7

Parmelee, J. H. & Roman, N. (2019). Insta-Politicos: Motivations for following political leaders on Instagram. Social Media + Society, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119837662

Pineda, A., Barragán-Romero, A. I. & Bellido-Pérez, E. (2020). Representación de los principales líderes políticos y uso propagandístico de Instagram en España. Cuadernos. info, (47), 80-110. http://dx.doi.org/10.7764/cdi.47.1744

Rooduijn, M., Pirro, A. L., Halikiopoulou, D., Froio, C., Van Kessel, S., de Lange, S. L. & Taggart, P. (2023). The PopuList: A database of populist, far-left, and far-right parties using expert-informed qualitative comparative classification (EiQCC). British Journal of Political Science, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123423000431

Quevedo-Redondo, R & Portalés-Oliva, M. (2017). Imagen y comunicación política en Instagram. Celebrificación de los candidatos a la presidencia del Gobierno. Profesional de la información/Information Professional, 26(5), 916-927. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.13

Sampietro, A. & Sánchez-Castillo, S. (2020). Building a political image on Instagram: A study of the personal profile of Santiago Abascal (Vox) in 2018. Communication & society, 33(1), 169-184. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.33.37241

Segado-Boj, F., Díaz-Campo, J. & Lloves Sobrado, B. (2016). Objetivos y estrategias de los políticos españoles en Twitter. índex. comunicación, 6(1), 77-98. https://bit.ly/4eoaT9g

Selva Ruiz, D. & Caro Castaño, L. (2017). Uso de Instagram como medio de comunicación política por parte de los diputados españoles: la estrategia de humanización en la “vieja” y la “nueva” política. Profesional de la Información, 26(5), 903-915. http://dx.doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.12

Slimovich, A. (2019). La mediatización contemporánea de la política en Instagram. Un análisis desde la circulación hipermediática de los discursos de los candidatos argentinos. Revista Sociedad, (39), 31-45. https://doi.org/10.62174/rs.2019.5088

Slimovich, A. & Beaudoux, V. G. (2022). Comunicación política e Instagram: la campaña electoral argentina 2021. Revista Argentina de Ciencia Política, 1(29), 109-138. https://doi.org/10.26422/aucom.2023.1201.car

Valera-Ordaz, L., Calvo, D. & López-García, G. (2018). Conversaciones políticas en Facebook. Explorando el papel de la homofilia en la argumentación y la interacción comunicativa. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (73), 55-73. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2018-1245

Waisbord, S. (2020). ¿Es válido atribuir la polarización política a la comunicación digital? Sobre burbujas, plataformas y polarización afectiva. Revista saap, 14(2), 248-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.46468/rsaap.14.2.a1