index●comunicación

Revista científica de comunicación aplicada

nº 15(01) 2025 | Pages 265-290

e-ISSN: 2174-1859 | ISSN: 2444-3239

Echoes of Depopulation on Twitter/X: the Conversation between 2019 and 2023

Ecos de la despoblación en Twitter/X: la conversación entre 2019 y 2023

Received on 02/07/2024 | Accepted on 22/11/2024 | Published on 15/01/2025

https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/15/01Ecosde

Belén Galletero-Campos | Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha

belen.galletero@uclm.es | https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9549-9507

Vanesa Saiz-Echezarreta | Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha

vanesa.saiz@uclm.es | https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1700-0296

Arturo Martínez-Rodrigo | Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha

arturo.martinez@uclm.es | https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2343-3186

Abstract: Depopulation in Spain has become increasingly present in politics and media in recent years. Under the theoretical perspective of public issue sociology, a methodology for observing the processes through which different actors discuss and negotiate solutions to a controversial situation, this paper aims to analyze the social debate on the issue since 2019, the year of the uprising of España Vacía (Empty Spain). In particular, we analyze the content on depopulation published on Twitter/X between May 2019 and May 2023, which assembles a total number of 328,714 posts involving 93,412 accounts. The results show a significant politicisation of the issue, with peaks of interest coinciding with election campaigns. The hatching of attention comes in 2019, when depopulation entered the discussion in national terms, while in 2023 there is a decline in interest that may result in a future withdrawal towards the territories directly affected.

Keywords: Depopulation; Publics; Twitter/X; Public Problems; Political Communication;

Social Media.

Resumen: La despoblación en España ha ganado presencia política y mediática en los últimos años. Bajo la perspectiva teórica de la sociología de los problemas públicos, que observa los procesos mediante los que diversos actores discuten y negocian soluciones a una situación controvertida, este trabajo se propone analizar el debate social sobre la cuestión desde 2019, año de la revuelta de la España vacía. En particular, se analiza el contenido sobre despoblación publicado en Twitter/X entre mayo de 2019 y mayo de 2023, que aúna un total de 328.714 publicaciones en las que se han visto implicadas 93.412 cuentas. Los resultados muestran una importante politización de la cuestión, con picos de interés en campañas electorales. La eclosión de la atención se sitúa en 2019, cuando emergió en la discusión en términos nacionales, mientras que en 2023 se aprecia un declive en el interés que podría traducirse en el futuro en un repliegue hacia los territorios directamente afectados.

Palabras clave: despoblación; públicos; Twitter/X; problemas públicos; comunicación política; redes sociales.

To quote this work: Galletero-Campos, Belén, Saiz-Echezarreta, Vanesa y Martínez-Rodrigo, Arturo. (2025). Ecos de la despoblación en Twitter/X: la conversación entre 2019 y 2023. index.comunicación, 15(1), 265–290. https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/15/01Ecosde

1. Introduction

The depopulation process in rural Spain is not a recent phenomenon (Collante and Pinilla, 2019), but in the last eight years it has become salient in politics (Pazos, 2022; Esparcia, 2021) and media (Saiz-Echezarreta et al., 2022; Verón Lassa and Hernández Ruiz, 2022). After the rural exodus in the 1950s and 1960s, there was a period of stability and even some drawing in of residents from abroad in the 1990s. Nevertheless, the 2008 economic crisis unleashed a second wave of depopulation when fewer employment opportunities became available in rural areas (González-Leonardo, López-Gay and Recaño, 2019). In many cities and towns, an aging population and the lack of a younger generation to take its place threaten the survival of those communities (Recaño Valverde, 2017), which has led the public there to mobilise and call for policies that would address depopulation or at least mitigate its effects.

The community association efforts that called for public services, investments and infrastructure in depopulated areas such as Teruel, Soria and Zamora began in the early 2000s (Amezaga and Martí Puig, 2012). With an initial focus on local politics, at that time there was no network of groups with shared interests, as would emerge later. Activism about depopulation on the part of city governments and local networks was also important in that first decade, especially in Aragón (Sáez, Ayuda and Pinilla, 2016) and Castile and León.

The growing public and political interest attracted the attention of other actors, including the media, which laid the groundwork for depopulation to be considered a national problem (Collantes, 2020). Along these lines, a milestone was the release of the title of the book La España vacía (Empty Spain) (Del Molino, 2016), which symbolically condenses the phenomenon and mobilised previously muted concerns (Castelló, 2024), bringing to the forefront of conversation in media.

Institutional progress, with rural depopulation becoming part of the portfolio of the Commission on Demographic Challenge (Royal Decree Act 40/2017) ran in parallel with preparations for the Revuelta de la España Vaciada (Revolt of Emptied Spain), a protest held in Madrid in March of 2019 where 83 associations from different provinces in Spain converged to demand the attention of the political classes and serve as a reminder of the existence of the rural sphere (Abellán-López, Pardo Beneyto and Pineda Nebot, 2021). This movement symbolically concentrated rural communities in the capital, and in turn led to a previously unknown visibility in media. This, alongside the national, regional and local elections in 2019 contributed to the emergence of España vaciada (Hollowed-out Spain or Emptied-out Spain) as a political actor (Sánchez-García and Delgado-García, 2024). This process led to more than 160 associations from 28 provinces to register as a political party (called «España vaciada») in September 2021 and appear with different branding in the areas where it was active (Esparcia, 2024).

Recent research has addressed the press coverage of depopulation (Castelló, 2024; Cuenca, Rebollo-Bueno and García-González, 2023; Sanz Hernández, 2016; Saiz-Echezarreta and Galletero-Campos, 2023). These studies reflect the progression of the debate between 2016 and 2020 that changed sociopolitical priorities (with an interruption due to the pandemic). In this context, the academy and the citizenry alike wonder if depopulation has solidified itself as a topic of public policy interest and a matter that can maintain long-term currency in institutional, political and media agendas, or if it has only been topic of passing interest that is destined to be limited to the territories directly affected.

1.1. Objectives

The main objective of this work is to perform a longitudinal analysis of the content of the debate on Twitter/X about depopulation during 2019-2023. This period is bookended by the announcements of regional elections in areas affected by depopulation, such as Castile-La Mancha, Aragón, Extremadura and Castile and León, held on 26 May 2019 and the elections held on 28 May 2023. Analysis of this public debate is an unexplored area of study, and the specific objectives are as follows:

1. Analyse the evolution of the social conversation about this societal problem on the social media platform in question and identify the moments of greatest activity on the topic.

2. Detect what kinds of actors have taken part in the debate and which have led the social conversation in terms of relevance and mediation between communities.

3. Analyse the discursive frameworks that have guided the debate about this public problem, while observing to what degree there are shared perspectives among the participants.

2. Theoretical Framework: Public Issue Sociology

This analysis is based on sociology of public issues, a theoretical perspective whose «main focus is to analyse the practices that lead to defining a given situation as problematic» (Pereyra, 2018: 122-124) and how certain matters are established as topics for debate in the public square through the actions of actors who formulate demands about them, propose solutions and debate about who should be responsible for implementing those solutions, all in a context of controversy and often uncertainty (Verturini and Munk, 2021). Not all social issues become public issues; not all matters generate institutional action or social movements, as happened during the decades of depopulation. Assigning the label of «problematic» to a situation is not enough. Instead, it must capture public attention, attract interest and be considered a matter of general concern (Gusfield, 2014). Likewise, problems are not defined as stable elements, since concerns and ways of addressing them change over time (Pereyra, 2018:124).

This perspective proposes observing the organisation of public life around debates about the definition of unfair or unjust situations and how to resolve them. Although at first glance this perspective may seem linked to nation-wide concerns, since the process includes an axis of general interest and institutional awareness of the problem, it may actually be applied at multiple levels. As a theoretical/methodological tool, it allows for orienting the exploration of how a public issue emerges and evolves while taking into account the stories, moral arguments and construction of evidence in the processes of making it a legitimate concern. At the same time, this approach analyses the actions of individuals and groups (organisations, institutions, platforms, media) in different public arenas as they participate and are brought in as affected by and/or responsible for the cause or solution of the problem. The arenas are the places where the actors emerge, are noticed and negotiate in their attempts to make their perspective the dominant one by claiming «ownership» of the problems (Gusfield, 2014: 76-80).

2.1. Twitter/X as an Arena for Discussion

A public issue’s process of emerging and unfolding -- which may or may not be successful in terms of its resolution or institutional acknowledgement -- occurs through an articulation of the problem in various public arenas (Cefaï, 2022). In the digital public sphere, social media acts as a special space for producing public discourse, political debate and social mobilisation and change.

Twitter/X, given its use parameters based on brevity, public content and its capacity to influence the agenda (López-García, Cano-Orón y Argilés-Martínez, 2017), is ideal for mapping actors and actions around public issues. Authors such as Halpin, Fraussen and Ackland (2021) consider it to be a key tool in political communication, given that posts are visible to all users, information circulates simultaneously and the combination of hashtags and mentions makes it easier to create topic-based audiences, since each user can follow other accounts without the permission of the owners of those accounts. Furthermore, unlike other social media platforms, Twitter/X is a site that is more effective for political mobilisation thanks to the weak ties between users. That is, connections on Twitter/X are usually between acquaintances, friends of friends or people who are even more distant. Such connections help create environments where information is more novel and perspectives are more varied than those that are found in communities with strong ties (Valenzuela, Correa and Gil de Zúñiga, 2017).

There is a tension on Twitter/X between spontaneity and planned strategic communication, and a certain degree of noise due to the algorithmic amplification of certain content (Congosto, 2018). Despite this, analysing the site’s content allows for an interpretation of the digital fingerprint of the actors and their relationships as evidence of their involvement and participation in defining and discussing perspectives that are the object of the present study.

In Spain, there is a large body of previous work that has studied the presence of various matters of public interest on this website. These include climate change (Loureiro y Alló, 2024), historical memory (Congosto, 2018); the engagement of the political classes in antifeminist discourse (Gutiérrez Almazor, Pando Canteli and Congosto, 2020) and in feminist discourse (Fernández-Rovira and Villegas-Simón, 2019) or the evolution of social movements such as 15M (an anti-austerity movement with an important protest on 15 March) (Gil Ramírez and Guilleumas García, 2017). In the case of depopulation, and following growing media attention on the topic, a diachronic evolution on the matter is observed wherein the social pulse of the topic from recent years is maintained.

3. Metodología

3.1. Sample

The present project is part of a wider ethnographic investigation that uses the follow the conflict strategy (Marcus, 1995: 95) to explore the debate about depopulation. After deciding on this qualitative approach, keywords in the form of hashtags were identified and these allowed for filtering and compiling a corpus. The sample of tweets in Spanish was obtained via the hashtags: #despoblación, #retodemográfico, #Españavacía, #EspañaVaciada, #Españadespoblada, #Españaabandonada y #LaEspañaSilenciada (in English: depopulation, demographic challenge, Empty Spain, Emptied Spain, Depopulated Spain, Abandoned Spain, Silenced Spain). Although some terms have been debated in the academic community (Molinero and Alario, 2022; Verón Lassa and Hernández Ruiz, 2022), these form the predominate framework that has been used to address depopulation in recent years. The variety of terms aims to include the greatest number of actors involved, in recognition of the fact that not all of them have the same discursive focuses.

The Twitter/X application programming interface (API) was used to gather the tweets. This allowed for a mass extraction of posts in a structured way with the Python programming language. The search was configured to identify tweets superficially containing the defined search tags. A total of 328,714 posts were gathered, including original tweets and retweets. Following that, an exhaustive preprocessing was conducted with Python in the leadup to the analysis of the hashtags in the corpus. First, the text was segmented by dividing each post into tokens and empty words or terms with no semantic load (such as articles and prepositions) were eliminated. Then, regular expressions in Python were implemented to clear the post text of external links that did not provide information relevant to this analysis. Lastly, RegEx was implemented to identify and extract the hashtags, with these being stored in a separate column so that they could be analysed separately.

To prepare the oriented graph matrix, the mentions were extracted from the tweets and retweets. This process made it possible to map the interactions and the direction of the conversation among the various actors on the social media platform and build the graphs. Thus, each user account was taken as a node and the mentions of other accounts in posts were assigned as the edges that connected these nodes. This allowed for the construction of a graphical representation of the information flow and the communication relationships between the accounts. This in turn facilitated later analysis of the conversational dynamic in the Twitter/X ecosystem.

Additionally, given that the conversation on Twitter/X tends to follow a pattern of heightened activity for periods of a few days with a focus on specific moments (Hoang, 2024), and taking the histogram into consideration, four sub-samples were generated in the time bands with the highest activity; October-November 2019; January 2020; March 2021; and January 2022.

3.2. Methods

This study is based on network analysis theory (Carrington and Scott, 2011), which is a means of using graphs to visualise complex sets of relationships between connected units, the way in which they are connected and their impacts (Kent, Sommerfeldt and Saffer, 2016). In addition to observing the individual position of the nodes in a network and defining their value in regard to the number and type of connections with other nodes, graph analysis also considers the form and density of the network set (Hansen, Schneiderman y Smith, 2011: 32).

The software Gephi (v 0.10.1) was used to calculate the statistical measures of centrality and modularity, as well as to visualise the positions of actors in the network. The centrality metrics considered in this study were the in-degree, which calculates the number of times that other actors mention an account; the eigenvector, which evaluates the relevance of a node based on its central position and the popularity of neighbouring nodes it relates to; and betweenness, which captures the importance of a node in bridging the gap between distinct communities (clusters).

Likewise, the modularity for each graph was calculated with the tool provided by Gephi, using the algorithm defined by Blondel et al. (2008). The Force Atlas 2 algorithm was used to visualise the graphs. In this visualisation, colours were used to identify the different clusters detected and characteristic vectors were used to scale the node sizes. In order to better interrogate the graphs and analysis, the results were also filtered by eigenvector value until the number of visible nodes was reduced to a figure of 250 to 300 most relevant nodes.

Lastly, the frequency of the most relevant hashtags in the dataset and the sub-samples was explored in order to identify the predominant topics and discursive framings.

4. Results

4.1. Changes over Time

Collantes (2020) used the apt metaphor «rural questions rose to the surface» in 2019 to suggest that media presence directed attention to «the situation in rural areas of the country and their perspectives about future changes, as well as the problem of territorial cohesion brought about by the highly unequal spatial distribution of the Spanish population».

Attention toward the depopulated rural areas reached its political zenith during the leadup to the national elections on 28 April 2019, during which all national parties included measures aimed at depopulation in their platforms. One of the motivations was the concern on the part of majority parties about possible vote fragmentation, especially in the eight provinces with three seats that were historically split between two parties. These ridings often align with territories facing demographic decline, as was noted in informational coverage about the campaign[1].

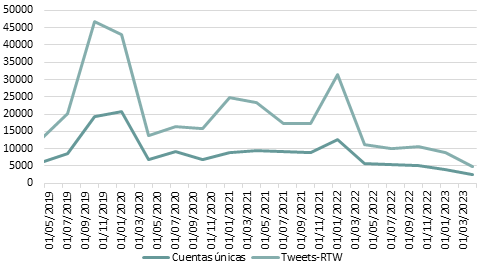

What happened in the following four years? Figure 1 shows the changes in the conversation on Twitter/X during the period relevant to this study and makes it possible to see the moments of highest activity, as well as a clear downward-trending line.

Figure 1. Temporal distribution of the accounts involved (n=93,512) and posts (n=328,714)

Source: Author’s own work.

In the evolution of posts and the number of accounts involved, there is a general base conversation level of between 5000 and 10,000 accounts during the four years considered in this study. The change line shows three stages: an initial phase characterised by its emergence into the debate between October 2019 and January 2020; a second phase, with a decreasing level of activity due to the start of the pandemic, during which the debate went through a latency period; lastly, there is a third phase with a new peak of conversation in January 2022, coinciding with the regional elections campaign in Castile and León, which is followed by a decline in the later months of 2023.

Regarding the high points, the moment of maximum activity coincides with the national elections held on 10 November 2019, in which Teruel Existe stood for the first time (37,642 posts between October and November 2019, 11.5% of the total). The conversation was also highly active in January 2020, coinciding with Pedro Sánchez becoming prime minister (34,453 posts, 10.5%). There is another peak, albeit a lower one, in January 2022 due to the regional elections campaign in Castile and León. That moment saw 27,220 posts, representing 8%. On the other hand, the regional elections held on 26 May 2019, Andalusian regional elections on 19 June 2022 and regional elections held elsewhere on 28 May 2023 did not generate a significant volume of discussion, despite the presence of organisations under the umbrella of España Vaciada and its success in regions such as Aragón, where they won three seats in the regional parliament.

4.2. Relevant Actors

Of the 93,412 accounts sampled, Table 1 shows the 20 that were consistently the most relevant during the four years considered in this study, according to the indications analysed. They are grouped into five categories: politics (profiles of parties and individuals), institutions, interest groups, media and other.

Table 1. Ranking of the 20 accounts with the highest levels of centrality

|

Eigenvector |

Betweeness |

In degree |

|

TeruelExiste_ (IG) |

TeruelExiste_ (IG) |

TeruelExiste_ (IG) |

|

SoriaYa (IG) |

SoriaYa (IG) |

SoriaYa (IG) |

|

Sanchezcastejon (POL) |

Redespanola (IG) |

Sanchezcastejon (POL) |

|

Mitecogob (INS) |

EspanaVaciada (IG) |

Mitecogob (INS) |

|

Teresaribera (POL) |

vox_es (POL) |

vox_es (POL) |

|

vox_es (POL) |

Imolina (POL) |

EsSilenciada (POL) |

|

PSOE (POL) |

Existimos_ (IG) |

Teresaribera (POL) |

|

Santi_ABASCAL (POL) |

Mitecogob (INS) |

PSOE (POL) |

|

EsSilenciada (POL) |

Pacoboya (POL) |

Santi_ABASCAL (POL) |

|

Existimos_ (IG) |

RDemografico (INS) |

Existimos_ (IG) |

|

EspanaVaciada (IG) |

Mcampovidal (MEDIA) |

Renfe (OTHER) |

|

Renfe (OTHER) |

CsCastillayLeon (POL) |

EspanaVaciada (IG) |

|

Jcyl (INS) |

SanidadRural (IG) |

Jcyl (INS) |

|

RDemografico (INS) |

SCeltiberica (IG) |

RDemografico (INS) |

|

jovenes_CyL (IG) |

Mjdelrio (OTHER) |

jovenes_CyL (IG) |

|

Desdelamoncloa (INS) |

PeriodistaRural (MEDIA) |

Pablo_Iglesias_ (POL) |

|

Congreso_Es (INS) |

sspa_network (IG) |

Desdelamoncloa (INS) |

|

Senadoesp (INS) |

CiudadanosCs (POL) |

Congreso_Es (INS) |

|

Pacoboya (POL) |

poder_rural (MEDIA) |

Albert_Rivera (POL) |

|

Pablo_Iglesias_ (POL) |

Fademur (IG) |

Mjdelrio (OTHER) |

Source: Authors’ own work.

When we consider the accounts that received mentions (indegree) and those that were connected to other important accounts (eigenvector), the politcal profiles stand out. This is true of both parties and national political leaders. The reason for the high centrality measures is that they are consistently addressed by members of the public, who mention them in their own posts when they make demands or ask questions of politicians. In order of relevance, institutions and interest groups are in second place. When we consider the betweenness figures, which measure the importance of certain accounts in acting as bridges between communities, the category with the highest figures is that of interest groups. The accounts of media organisations also return notable figures in the betweenness metric. This indicates that they are important nodes as intermediaries, since they tag and mention actors in the posts where they refer to actions on the part of institutions and/or groups making demands.

4.2.1. Political Parties

Although the accounts of political parties and their national spokespersons are the most relevant, significant differences are still observed between them (Table 2).

Table 2. Parties and political leaders and their eigenvector positions

|

PSOE |

VOX |

CIUDADANOS |

||||||

|

@PSOE |

8 |

@vox_es |

7 |

@CiudadanosCs |

28 |

|||

|

@sanchezcastejon |

4 |

@Santi_ABASCAL |

9 |

@Albert_Rivera |

21 |

|||

|

@EsSilenciada |

10 |

|||||||

|

PODEMOS |

PP |

|||||||

|

@ahorapodemos |

56 |

@GPPopular |

272 |

|||||

|

@Pablo_Iglesias_ |

22 |

@pablocasado_ |

38 |

|||||

|

@PODEMOS |

195 |

@NunezFeijoo |

1637 |

|||||

Source: Authors’ own work.

The PSOE stands out throughout this period due to its position in government and also for its commitment to the matter. This involvement extended to its platform and its national legislative agenda (approval of the Ministry for Demographic Challenge in 2020 and the 130 Measures Plan for the Demographic Challenge in March 2021) and to the regional level (laws addressing depopulation in Castile-La Mancha and in Aragón). In the same vein, the president of Government is the most active leader among the politicians considered here, as he published seven original tweets and retweeted five others.

Next, VOX is also notable because of its strategic use of the #Españasilenciada media campaign, which was executed between 26 and 31 January 2022 in the leadup to the regional elections in Castile and León. In fact, @EsSilenciada (with 5409 followers and 557 posts) has the ninth highest eigenvector among all accounts analysed. Abascal did not post individual tweets, but he did make 12 retweets in this campaign.

The other parties sit at less important rankings. The accounts for Ciudadanos and its leader Albert Rivera (who posted on 3 original tweets) participated in the debate only during its first year, during the 2019 election campaign in Castile-La Mancha and Castile and León.

The centrality metrics for Podemos and its leader are explained by their participation during the breakout period: in September there is mention of the meeting among the constituent associations of España Vaciada with Pablo Fernández Santos, secretary of Ámbito Rural and España Vaciada, and with two original tweets by Pablo Iglesias during the 10 November election campaign.

Far from the relevant leading positions are the accounts of the Partido Popular and its leaders Pablo Casado (with 2 tweets) and Alberto Núñez Feijóo, who did not actively participate. This group did not participate in the debate which, as Esparcia (2024) points out, could be due to the party not having prepared a «simple and clear discourse that was attractive to the electorate» on this matter.

4.2.2. Interest Groups

During the period analysed in this study, the interest group movement led a politicisation process that started with Teruel Existe standing in the November 2019 elections. This organisation was founded in 1999 and occupies a prominent position in the three centrality metrics, along with Soria Ya (which was founded in 2001). These groups, with their relatively long histories, are the seed of the España Vaciada platform (@EspañaVaciada) which brings together more than 100 organisations. While these other organisations do not have the visibility of @TeruelExiste_, @SoriaYa and @EspañaVaciada, of the 100 most relevant are @JaenMereceMas (the only group in España Vaciada that stood for office in the 2022 Andalusian elections), @sostalavera, @cáceres_viva, and two groups focused on local concerns, @SalvemosBéjar and @VueltadelTrenBZ.

Additionally, the interest group accounts that served as connectors with different communities were: @redespanola, @Existimos_, @SanidadRural, @SCeltiberica, @sspa_network and @fademur. Some citizen influencers also stand out for their activism on the matter and this has earned them positions of high relevance. Two examples are @mjdelrio (15th in eigenvector ranking), who uses the identity MJ Dictatriz #SanidadPública, and Virgina Hernández (24th in the eigenvector ranking), who holds herself out as a reconverted philologist, holder of a master’s degree in digital journalism and punk folklorist. These cases show that individuals can have an important impact on the circulation of content that makes demands for a cause.

4.2.3. Institutions and Media

If we consider the actions launched by political actors and platforms in previous years, the conversation on Twitter/X shows the degree of success in institutionalising the public issue of depopulation. Relevant players in the debate are, among others, the Secretary General’s office (@RDemografico) and the Ministry for Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge (@mitecogob), along with their leaders (@Teresaribera, @Pacoboya) and advisors (@imolina), as well as the Government’s public relations office (@desdelamoncloa) and, to a lesser degree, the Congress and Senate. These accounts, as we shall see, coordinate along with and reinforce the actions of the PSOE and its leaders.

Although media accounts do not appear in the highest ranked slots, they are important in that their content is often shared in retweets and comments containing links to their news, although the media organisation’s account is not always mentioned or tagged. The account of the organisation that produced the content is likewise not always the source of the tweet. The centrality metrics do not take these shares into account. That notwithstanding, some media accounts do appear in the ranking, such as that of the journalist Manuel Campo Vidal, founder of the Red de periodistes rurales (Rural Journalists Network) (also appearing as @PeriodistaRural) and the now-defunct outlet @poder_rural.

4.3. Stages and Framming

4.3.1. Breakout Period: May 2019-January 2020

As can be seen in Figure 1, there was a gradual increase in posts starting in May 2019, with the highest point coming between October 2019 and January 2020. Although there were regional elections on 26 May 2019 in all depopulated regions, there was no significant volume of participation online compared with that associated with the national campaigns in the leadup to the 10 November elections.

In October, depopulation erupted into the conversation with the symbolic work stoppage on the 4th of that month organised by the España Vaciada Platform with the slogan #YoParoPorMiPueblo (I’m stopping for my village), the hashtag that had the highest circulation, at 6214 mentions. That action was part of the work of organisations to define and bring visibility to depopulation as a problem, and to make demands and call for measures to address it. According to public issue sociology, this is what happens in the initial emergence and shaping phase.

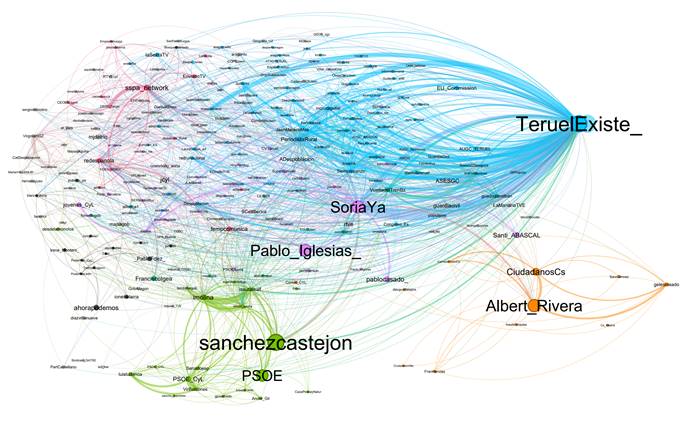

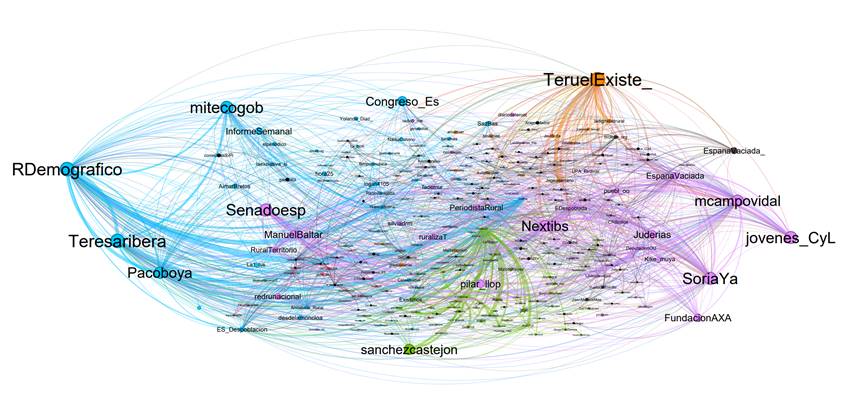

Figure 2, which covers October and November 2019 with 37,642 posts, 17,930 nodes and 54,059 interactions, includes the campaign #yoparopormipueblo identified by the pink cluster.

Figure 2. Graph of interactions in October and November 2019

Source: Authors’ own work.

In the circulation of #YoParoPorMiPueblo, the key organisations in España Vaciada stand out. However, a variety of other profiles participate as well, such the Red de Áreas Escasamente Pobladas del Sur de Europa (Southern Sparsely Populated Areas; @sspa_network), the Red Española de Desarrollo Rural (Spanish Network for Rural Development; @redespañola), which includes the groups LEADER and the Federación de Municipios y Provincias (@fempcomunica). Accounts of media organisations also stand out, as they were tagged to increase the impact of the symbolic stoppage. Additionally, various political leaders, including the prime minister, were involved with the campaign. In fact, this was the only time in the four years considered here that Pablo Iglesias and Albert Rivera posted tweets about depopulation. This participation indicates that the topic was already part of institutional agendas and was accepted as an area where political intervention was necessary in certain political circles.

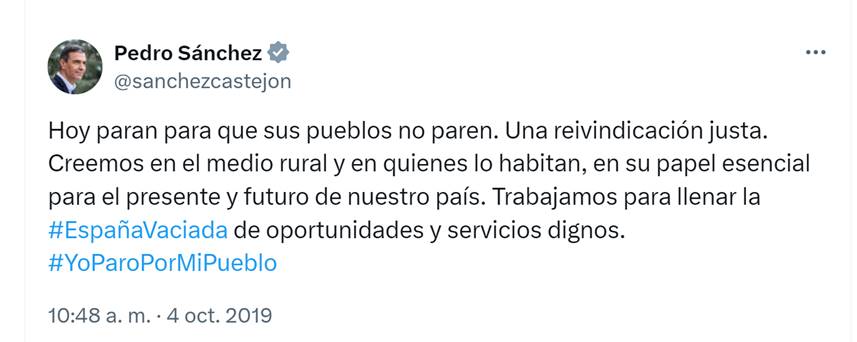

Image 1. Post by the prime minister in the #YoParoPorMiPueblo campaign

Public mobilisation in October coincided with the candidacy of Teruel Existe as a group of electors for the 10 November elections, creating the climate for a campaign in which depopulation would be one of the important topics. The graph also shows the relevance of political actors during this electoral period, mostly due to the citizenry and, in particular, the España Vaciada platforms making demands for action and a greater debate about depopulation. In fact, in November interactions about the debate held on RTVE on the 5th of that month stand out.

It would be appropriate to think, as public issue sociology proposes, that this topic has become part of the political, media and societal agenda once it becomes national in scale, even more so when it becomes a topic considered in parliamentary politics. The conversation undoubtedly became even more intense with the transformation of Teruel Existe as a political group of electors and especially in light of its results. The collective won one representative in the Congress and two in the Senate. #Teruelexiste was the second most used hashtag in this period, at 1413 mentions. None of the remaining hashtags reached even a thousand mentions.

This period extended until January 2020, when the vote of the Teruel Existe representative was decisive in forming a government. The movement took a strategic position, and this is reflected in the conversation that month, which featured 22,315 posts from 14,174 accounts (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Graph of interactions in January 2020

Source: Authors’ own work.

This moment marks a significant change: after the electoral success and the strategic manoeuvring by Teruel Existe that saw Pedro Sánchez become head of government, the debate about depopulation shifted to the political gamesmanship between parties, where the Teruel group was caught up in the left/right divide. In January, the most notable hashtags reflect this: #teruelexiste (8286 mentions), #teruel (1138 mentions) and #yovoyateruel (933). The last of these was a hashtag created in response to #boicotteruel (305 mentions) that was launched to challenge the support for Sánchez’s candidacy for the prime ministership. Its relevancy is not fully represented in this sample because it was not always posted with other hashtags about depopulation.

That same month, @TeruelExiste and @sanchezcastejon shared a ranking with @SoriaYa for its criticism of Javier Antón (@javieranton, PSOE) and Tomás Cabezón (@tcabcas, PP), both representatives from Soria who had some of the highest centrality rankings. @SoriaYa intervened as a social movement and demanded action in support of policies to address depopulation. It would not become a political actor as it did not put forward a slate of candidates until two years later.

Image 2. Post by @SoriaYa

Fuente: Twitter/X.

The events of that moment provide a good example of how activism formulates demands and identifies the actors responsible for causing the problem. One example is Renfe’s (the Spanish state-owned railway company) announcement of the closure of ticket offices in stations with less than 100 daily travellers. Various accounts reacted to this, including the Federal Rail Sector of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (@SFFCGT), which is the blue cluster in Figure 3. This account criticised the measure in a series of tweets and tagged media and institutional offices to increase visibility.

In the dataset from the breakout period, the request for public services remains strong, as does the call to keep the focus on depopulation. This call had been seen in the preceding months in order to maintain depopulation as a shared problem requiring collective solutions. At the same time, depopulation was becoming caught up in electoral forces and parliamentary negotiations.

|

Image 3. Post by @SFFCGT

Source: Twitter/X.

Imagen 4. Post by @SoriaYa

Source: Twitter/X.

|

|

4.3.2. Latency Period: February 2020-December 2021

After the lapse in public attention caused by the pandemic, interactions started to climb and reached a high point in March 2021, with 12,592 posts among 6189 nodes participating and leading to 17,087 interactions (Figure 4). This coincided with the anniversary of the March 2019 uprising (the revuelta).

Figure 4. Graph of interactions in March 2021

Source: Authors’ own work.

This is a stage marked by action from the Socialist government to address the topic and its institutional dominance, most especially regarding the Secretariat for Demographic Challenge, the minister Teresa Ribera and the secretary Paco Boya. The Secretariat opened its account @RDemografico on 10 December 2020 with the hashtag #elretodetodos (the challenge for everyone), which it would use three months later to launch the Plan de 130 Medidas (the 130 Measures Plan). Later, that hashtag would take on a downward trajectory. The hashtag was mentioned 2216 times between 2020 and 2021 while between 2022 and 2023 it was only mentioned 255 times.

Analysis of the accounts that used hashtags proposed by the Ministry (#elretodetodos, #retodemográfico) provides evidence that it is a fundamentally institutional framing -- and one by the Socialist party at that. They are not used by España Vaciada or other political actors, nor to frame interventions in the debate or otherwise participate in the debate. This lack of shared hashtag use could be responsive to the interest of each actor to “take over” the public issue and solidify itself as the dominant voice.

During this latency period, the interactions surrounding Manuel Campo Vidal also stand out. He is a journalist and the founder of the Next Education business school which has a chair on depopulation. In March 2021, coinciding with the anniversary of the March 2019 revuelta, the school released study on the perception of the advances in hollowed-out Spain.

Specifically, the anniversary also had an important impact on the community of platforms composed of ordinary members of the public, as shown by the highest-circulation hashtags that month: #siguelatiendo (Still beating) with 1143 mentions and #sos (the international emergency distress signal) with 416 mentions. The first alludes to the heart of the uprising, which is still beating despite the halt brought about by the pandemic; the second hashtag keeps calling for urgent intervention by public administrations in the affected territories. Nevertheless, the public participation groups did not commit to one slogan that would be used in later years. Thus, #siguelatiendo in 2021 would become #somoselmañanadelospueblos in 2022 (101 mentions) and #TerritoriosdeSacrificioNo (76 mentions) in 2023, showing a downward trend in attention on those dates.

4.3.3. Period of Reactivation and Decline: January 2022-May 2023

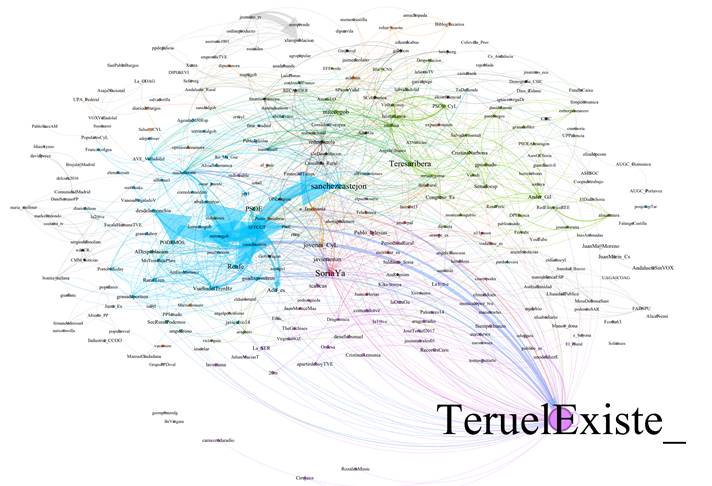

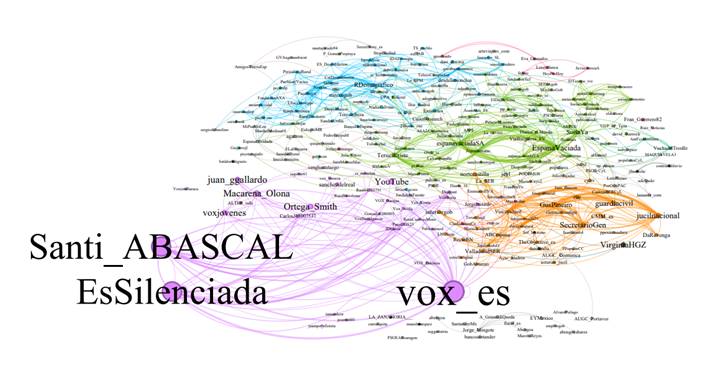

This period has its peak in January 2022, at the same time as the campaign for elections in Castile and León, which were held on 13 February, featuring 15,870 posts with 8000 nodes and 18,943 interactions.

Figure 5. Graph of interactions in January 2022

Source: Authors’ own work.

During this month, VOX actively participated in the debate for the first time. That party capitalised on the conversation and held itself out as the driving force behind the depopulation debate thanks to an electoral campaign focused on defending rural areas with the slogan «Siembra» (Sowing seeds) and the launch on 26 January 2022 of a series titled «La España silenciada». The pink cluster in Figure 5 shows the VOX representatives and the account for the @EsSilenciada campaign. Additionally, the hashtag #laespañasilenciada was mentioned 7709 times. With this figure, it was not only the most mentioned hashtag that month, but also the eighth most mentioned over the four years in the sample. Using this hashtag and following a centralised campaign logic, VOX created its own discursive space cut off from other communities. Its framing was exclusionary and was accessible only to members and sympathisers of the party.

That month, as figure 5 shows, the clusters are tightly defined. Blue is the interaction surrounding the Secretariat for Demographic Challenge and orange, again, is a call for and formulation of demands linked to the public issue. In this case, the call is aimed at the Guardia Civil and seeks to add more officers to ensure the safety and security of depopulated rural areas.

Finally, the green cluster corresponds to the España Vaciada groups, which during the reactivation phase (and before the decline) completed their politicisation process. Among their objectives was to solidify the depopulation problem as a matter of general interest. During the elections in Castile and León, the centrality of Teruel Existe and Soria Ya was shared with accounts like @EspañaVaciada and @EspañavaciadaSA (Salamanaca), although the leading role of VOX reduced the influence of these and other accounts.

The success of Teruel Existe in 2019 and Soria Ya in February 2022 almost certainly influenced the decision to create the Federación de Partidos de España Vaciada (the Federation of Parties from Emptied Spain), comprising Teruel Existe, España Vaciada, Aragón Existe, Soria Ya, Cuenca Ahora and Jaén Merece Más. The organisation was launched in November 2022 with a view toward the regional elections on 28 May 2023 in which the members ran candidates under their own electoral brands.

This final step in the politicisation process coincided with the phase of decline in which there is a minimum base level of conversation with almost no spikes. No substantial increases were observed in the Andalusian elections held on 19 June 2022 nor in the regional elections on 28 May 2023 which were held in areas affected by depopulation (during the latter, the Aragón chapter of Teruel Existe won three seats in the Aragón regional parliament).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The present study analysed the conversation about depopulation held on the Twitter/X social media platform between 2019 and 2023. Although the sample was collected by using keywords, and this may omit posts on the topic that did not use any of those terms, the use of keywords that were characteristic to this social media platform and the volume of 328,714 posts allows for a fairly precise approach to the central profiles involved in content circulation and to the matters that rose to the fore on the platform.

Within the framework of public issue sociology, the baseline assumption is that there is a link between publicity and circulation of information about a problem and the development of public interest in that problem (Queré, 2017). In this case, the research was guided by the question of whether depopulation has remained relevant, captured attention and formed wide participative audiences, or if its presence in the digital public sphere has diminished. To provide an answer, evidence was drawn from debate on Twitter/X and below some key interpretations are presented.

Prominent actors in the conversation as well as key moments of heightened activity confirm that the issue has been taken up in national politics. At that scale, public issues are considered to be of interest to the entire citizenry and not just for particular groups. That notwithstanding, since the elections in November 2019 until Pedro Sánchez took office in January 2020, the debate was not about depopulation specifically. Rather, depopulation acted as a tangential topic or a link between actors who were discussing national politics and the future head of government. This is reinforced by the scant presence of regional leaders and the low influence on the debate during the regional campaigns in 2023, and it reflects a certain lack of substantial debate about specific policies on depopulation. The fact of mentioning empty/emptied Spain does not always mean that the specific problems in depopulated areas such as sustainability, finances, local development or energy transition are mentioned as well.

Regarding the positions of political actors, not all political formations had the same influence. The PSOE capitalised on the depopulation question on Twitter/X, while the Partido Popular was irrelevant and did not organise effective discourse on social media. Podemos and Ciudadanos participated only during the breakout period and, lastly, VOX intervened late and only on one occasion, creating a specific hashtag for the electoral campaign.

The records of digital activity on the part of the interest group movement shows evidence of its transformation and politicisation. Its entry into the political arena starting in 2019 is due to a structure of favourable political opportunities (Abellán López et al., 2021). Esparcia (2024) further supports the thesis that the sociopolitical context that was beneficial to the interest groups from 2019 to 2021 changed substantially in 2022 and 2023. The downward pattern may have made it harder for these groups to solidify themselves in their set of territories. In the sample, it was observed that aside from Teruel Existe, Soria Ya and the general account of España Vaciada, there are no notable accounts from other areas.

The breakout on the national political stage, in terms of both media (Saiz-Echezarreta et al., 2022) and politics (Esparcia, 2024; Sánchez-García, et al., 2024) serves a condition for depopulation to enter the public sphere as a public issue, as is corroborated by the Twitter/X analysis. This is due to the fact that the national level means that the issue concerns the entire citizenry and is assumed as a question of state. This is even more so in the case of depopulation, in which the story of the España Vaciada movement -- in transforming the concept of empty Spain (Castelló, 2024) -- oriented itself toward assigning responsibility to institutional and political actors for the situations in those territories.

After the breakout period, the pandemic did not make the topic irrelevant, as it continued to capture attention and drive interactions at various times. In spite of this, the downward trend has not reversed. The framing of depopulation as a public policy issue and, specifically, one with electoral implications, has negatively affected the debate and its ability to keep the public’s attention. It would be necessary to expand the research about the trajectory of politicisation of the citizen movement, while exploring the interdependence between its fragility in some affected areas and the movement’s capacity to remain visible and active in the public sphere.

Currently, the decline in the volume of conversation about depopulation aligns with the electoral returns, which did not meet the expectations of the España Vaciada movement. Today, these political groups lack representation in Congress and the Senate, and only hold seats in regional parliaments in Castile and León and Aragón. Later ethnographic follow-up to this analysis shows that this lack of attention and the poor electoral results were still the case during the general election campaign in July 2023 and the European elections in June 2024. Among the reasons for this decline could be the complex international political context, which has diverted attention to conflicts outside Spanish borders. Furthermore, it could be the case that, as Esparcia (2024) points out, there is relatively little controversy about depopulation and there are actually broad areas of agreement among various political formations.

Perhaps the conversation about depopulation will continue to shrink and end up limited to the communities that are most directly affected. That said, it must be borne in mind that defining the contours of public issues is an open process that modifies and adapts itself to new sets of facts, the actions of stakeholders, the emergence of new issues and the development of narratives and framings that challenge previous assumptions and allow for conceiving of the problem in new terms.

Ethics and Transparency

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

R+D+i Project ‘Mediatized problems and audiences: emotions and participation’ [Problemas y públicos mediatizados: emociones y participación] (PID2021-123292OB-I00), in the State R&D&I Program for Knowledge Generation Projects, call for proposals 2022, Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation.

Author Contributions

|

Autor 1 |

Autor 2 |

Autor 3 |

|

|

Conceptualización |

X |

X |

|

|

Curación de datos |

|

|

X |

|

Análisis formal |

X |

X |

|

|

Adquisición de financiamiento |

|

X |

|

|

Investigación |

X |

X |

|

|

Metodología |

|

X |

X |

|

Administración de proyecto |

|

X |

|

|

Recursos |

X |

X |

X |

|

Software |

|

|

X |

|

Supervisión |

X |

X |

X |

|

Validación |

|

X |

X |

|

Visualización |

|

X |

X |

|

Escritura - borrador original |

X |

X |

X |

|

Escritura - revisión y edición |

X |

|

|

Data Availability Statement

Martinez, Arturo (2024), «Depopulation Tweets», Mendeley Data, V1. https://doi.org/10.17632/dxys8zt6ny.1

References

Abellán López, M.A., Pardo Beneyto, G. y Pineda Nebot, C. (2021). El movimiento social «La España Vaciada». Una aproximación a sus plataformas reivindicativas. En C.I. Molina Bulla, C. Pineda Nebot, T. Ferreira Dias y M. A. Marques Ferreira (Eds.), Participación social y políticas públicas en Iberoamérica (págs. 75-98). Universidad Externado.

Amezaga, I. y Martí Puig, S. (2012). ¿Existen los Yimbis?: Las plataformas de reivindicación territorial en Soria, Teruel y Zamora. Revista Española De Investigaciones Sociológicas, 138, 3–18. https://doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.138.3

Benkler Y., Roberts H., Faris R., Solow-Niederman A. y Etling B. (2015). Social mobilization and the networked public sphere: Mapping the SOPA-PIPA debate. Political Communication, 32(4), 594–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.986349

Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J. L. Lambiotte, R. y Lefebvre, E. (2008). Fast unfolding of communities in large networks, Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 10.

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.0803.0476

Carrington, P. y Scott, J. (2011). Introduction. En P. Carrington y J. Scott (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis Social network analysis. Sage.

Castelló, E. (2024). Arqueología del vacío: un estudio periodístico (2016-2021). Papeles del CEIC, 1, papel 292, 1-22. http://doi.org/10.1387/pceic.24010

Cefaï, D. (2022). The Public Arena. A pragmatist concept of the public sphere. En N. L. Gross, I. A. Reed y C. Winship (Eds.), The New Pragmatist Sociology: Inquiry, Agency, and Democracy (pp. 377-405). Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/gros20378-015

Collantes, F. y Pinilla, V. (2019). ¿Lugares que no importan? la despoblación de la España rural desde 1900 hasta el presente. Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza.

Collantes, F. (2020). Tarde, mal y... ¿quizá nunca? La democracia española ante la cuestión rural. Panorama Social, 31, 15-32.

Congosto, M. (2018). Digital sources: a case study of the analysis of the Recovery of Historical Memory in Spain on the social network Tw. Culture & History Digital Journal, 7 (2), e015. https://doi.org/10.3989/chdj.2018.15

Cuenca, C., Rebollo-Bueno, S. y García-González, J.M. (2023). Los discursos demográficos como herramienta político-mediática. El caso de la prensa española. Teknokultura: Revista de Cultura Digital y Movimientos Sociales, 20 (1), 37-47. http://doi.org/10.5209/tekn.81161

Del Molino, S. (2016). La España vacía. Turner.

Esparcia, J. (2021). La despoblación: emergencia y despliegue de políticas públicas en Europa y en España. En Asociación Española de Geografía y Universidad de Valladolid (Ed.), Espacios rurales y retos demográficos: Una mirada desde los territorios de la despoblación (pp. 179–149). Asociación Española de Geografía.

Esparcia, J. (2024). Rural Depopulation, Civil Society and Its Participation in the Political Arena in Spain: Rise and Fall of ‘Emptied Spain’ as a New Political Actor? En E. Cejudo-García, F.A. Navarro-Valverde y J.A. Cañete-Pérez (Eds.), Win or Lose in Rural Development. Case studies from Europe (pp. 39-63). Springer.

Fernández-Rovira, C. y Villegas-Simón, I. (2019). Comparative study of feminist positioning on Twitter by Spanish politicians. Anàlisi: Quaderns de Comunicació i Cultura, 61, 77-92.

https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/analisi.3383

Gil Ramírez, H. y Guilleumas García, R.M. (2017). Redes de comunicación del movimiento 15M en Twitter. Redes: revista hispana para el análisis de redes sociales, 28 (1), 135-146.

https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/redes.670

González-Leonardo, M., López-Gay, A. y Recaño, J. (2019) Descapitalización educativa y segunda oleada de despoblación. Perspectives Demogràfiques, 16, 1-4. https://doi.org/10.46710/ced.pd.esp.16

Gusfield, J. (2014). La cultura de los problemas públicos. El mito del conductor alcoholizado versus la sociedad inocente. Siglo XXI.

Gutiérrez Almazor, M., Pando Canteli, M. J. y Congosto, M. (2020). New approaches to the propagation of the antifeminist backlash on Twitter. Revista de Investigaciones Feministas, 11(2), 221-237. https://doi.org/10.5209/infe.66089

Halpin, D. R., Fraussen, B. y Ackland, R. (2021). Which Audiences Engage With Advocacy Groups on Twitter? Explaining the Online Engagement of Elite, Peer, and Mass Audiences With Advocacy Groups. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 50(4), 842-865. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764020979818

Hansen, D.L., Shneiderman, B. y Smith, M.A. (2011). Analyzing social media networks with NodeXL: insights from a connected world. Elsevier.

Hoang, T. T. (2024). Where are we when the community looks for us? A social network analysis of the self-organized network #TwitterFoodBank. Communication and the Public, 9(1), 36–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/20570473231213675

Kent, M. L., Sommerfeldt, E. J. y Saffer, A.J. (2016). Social networks, power, and public relations: Tertius Iungens as a cocreational approach to studying relationship networks. Public Relations Review, 42 (1), 91-100.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.08.002

López-García, G.; Cano-Orón, L. y Argilés-Martínez, L. (2017). Circulación de los mensajes y establecimiento de la agenda en Twitter: el caso de las elecciones autonómicas de 2015 en la Comunidad Valenciana. Trípodos, 39, 163-183. https://raco.cat/index.php/Tripodos/article/view/335042

Loureiro, M.L. y Alló, M. (2024). Feeling the heat? Analyzing climate change entiment in Spain using Twitter data. Resource and Energy Economics, Volume 77, 101437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reseneeco.2024.101437

Marcus, G. E. (1995). Ethnography in / of the world system. Annual Review of Anthropology, 24, 95-117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463499605059232

Molinero, F. y Alario, M. (2022). Una mirada geográfica a la España rural. Revives.

Pazos, S. (2022). «Emptied Spain» and the limits of domestic and EU territorial mobilisation. Revista Galega de Economía, 31(2), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.15304/rge.31.2.8365

Pereyra, S. (2018). La estabilización de un problema público. La corrupción en la Argentina contemporánea. En J.C. Bernal, A. Murrieta, G. Nardacchione, y S. Pereyra (Eds.), Problemas públicos: controversias y aportes contemporáneos (pp.122-174). Instituto Mora.

Quéré, L. (2017). Introducción a una sociología de la experiencia pública. Revista Entramados y perspectivas- Carrera de Sociología, 7 (7), 228 – 263. https://doi.org/10.62174/eyp.2601

Recaño Valverde, J. (2017). La sostenibilidad demográfica de la España vacía. Perspectives Demographiques, 7, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.46710/ced.pd.esp.7

Sáez, L. A., Ayuda, M. I. y Pinilla, V. (2016). Pasividad autonómica y activismo local frente a la despoblación en España: el caso de Aragón analizado desde la Economía Política. AGER: Revista de Estudios sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo Rural, 21, 11-41. https://doi.org/10.4422/ager.2016.04

Saiz-Echezarreta, V., Galletero-Campos, B., Castellet, A. y Martínez-Rodrigo, A. (2022). Evolution of the public problem of depopulation in Spain: longitudinal analysis of the media agenda. Profesional De La información, 31(5). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.sep.20

Saiz-Echezarreta, V. y Galletero-Campos, B. (2023). Despoblación, metáforas y discurso informativo. En C. Navarro, A. R. Ruiz Pulpón y F. Velasco Caballero (Dirs.), Despoblación, territorio y gobiernos locales (pp. 27-47). Marcial Pons.

Sánchez-García Á. y Delgado-García M. (2024). ¡Aquí no hay quien viva! El éxito electoral de las candidaturas de la España vacía. Papeles del CEIC, 1, papel 292, 1-27.

https://doi.org/10.1387/pceic.24103

Sanz Hernández, A. (2016). Discursos en torno a la despoblación en Teruel desde la prensa escrita. AGER: Revista de Estudios sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo Rural, 20, 105-137.

https://doi.org/10.4422/ager.2016.01

Valenzuela, S., Correa, T. y Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2017). Ties, Likes, and Tweets: Using Strong and Weak Ties to Explain Differences in Protest Participation Across Facebook and Twitter Use. Political Communication, 35(1), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1334726

Venturini, T. y Munk, A. K. (2021). Controversy Mapping. A Field Guide. Cambridge.

Verón Lassa, J. J. y Hernández Ruiz, J. (2022). Los términos «España vacía, vaciada y despoblada»: significado y presencia en la conversación mediática. En M. J. García Orta y R. Martín Santos (Coords.), El poder de la comunicación: periodismo, educación y feminismo (pp. 235-259). Dykinson.