index●comunicación

Revista científica de comunicación aplicada

nº 15(1) 2025 | Pages 53-75

e-ISSN: 2174-1859 | ISSN: 2444-3239

Advertising Literacy in the Classroom:

The Influence of Familiarity and Habitat

Alfabetización

publicitaria en el aula:

influencia de familiaridad y hábitat

Received on 05/09/2024 | Accepted on 23/11/2024 | Published on 15/01/2025

https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/15/01Alfabe

Ana Pastor-Rodríguez | Universidad de Valladolid (España)

ana.pastor.rodriguez@uva.es | https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1787-7939

Belinda de Frutos-Torres | Universidad de Valladolid (España)

mariabelinda.frutos@uva.es | https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9391-8835

Abstract: Recognising an advertising format or knowing how the advertising industry works does not necessarily imply advertising literacy. This experimental study tests the effect of a classroom action on improving advertising literacy based on habitat (rural and urban) and familiarity with the source (known influencers). The sample is made up of 62 students between 12 and 16 years of age. The action shows an improvement in the identification of advertising content, and the source and classification of commercial content, but not in the recognition of persuasive tactics. Differences are found in the rural habitat in correctly identifying advertising content, however, no effects associated with the familiarity of influencers were found. To carry out effective actions, it is important to bear in mind the situational context, work over an extended period of time, introduce a wide range of cases and look more deeply into persuasive strategies.

Keywords: Adolescence; Advertising Literacy; Social Media; Advertising Strategies; Familiarity; Educational action.

Resumen: Reconocer un formato publicitario o conocer el funcionamiento de la industria publicitaria no implica alfabetización publicitaria. El estudio experimental pone a prueba el efecto de una intervención en el aula en la mejora de alfabetización publicitaria en función de la de la familiaridad con la fuente (influencers conocidos) y el hábitat (rural y urbano). La muestra son 62 estudiantes entre 12 y 16 años. La intervención evidencia una mejora en la identificación del contenido publicitario, de la fuente y la clasificación del contenido comercial, pero no el reconocimiento de las tácticas persuasivas. Se encuentran diferencias en el hábitat rural para identificar correctamente los contenidos publicitarios, sin embargo, no se encontraron efectos asociados a la familiaridad de los influencers. Para conseguir intervenciones eficaces es importante tener presente el contexto situacional, trabajar a lo largo del tiempo, introducir un amplio abanico de casuísticas y ahondar en las estrategias persuasivas.

Palabras clave: adolescencia; alfabetización publicitaria; redes sociales; estrategias publicitarias; familiaridad; intervención educativa

To cite this work: Pastor Rodríguez, A. and de Frutos.Torres. (2025). Advertising Literacy in the Classroom: The Influence of Familiarity and Habitat. index.comunicación, 15(1), 53-75. https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/15/01Alfabe

1. Introduction

The smartphone has become an indispensable device which allows users to access leisure, entertainment, social relationships and news, among other options (Feijoo & García-González, 2019; De Frutos-Torres et al., 2020). 96% of over-16s choose it to connect to the internet, more than laptops (78%), Smart TVs or Tablets (70%) (GFK, 2021). Only 7% never use it when watching television (GFK, 2021).

Smartphone use has become near-universal since 2015, when 95% of users had a smart device (Growth from Knowledge [GFK] and nPeople, 2019). Lower rates and the option of using messaging applications, apart from calls (Plokiko, 2018) have favoured the use of smartphones at ever-younger ages. 70.6% of children between 10 and 15 years of age have a smartphone. Use by age: at 10 years old only 23.3% of children have the device, at 11 the figure rises to 45.7% of the group, by 12 it has reached 72.1%, at 13 it is at 88.2% and between 14 and 15 years of age the figure rises to over 94% of minors (Spanish National Institute of Statistics [INE], 2024). The amount of time spent on social media follows the same trend. Average daily use of social media by minors between 10 and 18 years old in Spain is 59 minutes a day, a figure that is greater than the use in the USA (46 minutes/day), the UK (55 minutes) or France (53). Regarding social media, 96% of these minors use YouTube, 61% TikTok, 55% Instagram, 37% X, 34% Facebook, and 33% BeReal (Qustodio, 2023).

This fact poses a problem considering that while minors have access to content that requires adult supervision to be correctly understood and assimilated (Dans Álvarez-de-Sotomayor et al., 2021), fully 39.9% of parents do not exercise any control, and those who do so tend towards restrictive rather than educational strategies (Smahel et al., 2020; AIMC, 2024). As the children get older, particularly in the transition from primary to secondary education, they face such content alone as they no longer share leisure time in the company of adults (Saraf et al., 2013; Padilla et al., 2015; Suárez-Álvarez et al., 2020).

This situation exposes minors to a host of digital risks such as access to inappropriate content, sexting, cyberbullying, grooming (Orosco & Pomasunco, 2020), and addictions to gambling (Rial et al., 2018), the internet, or social media (Casaló & Escario, 2019). These being risks that can generate physical, emotional, and psychological problems, affect the minor's socialisation, and even end in suicide (Navarro, 2017; Velasco & Gil, 2017), especially in adolescence when interaction with their peers involves the development of their identity.

Such issues include persuasive narratives, particularly advertising on social media, as these platforms break the rigidity that characterises other media, including digital media, and mix playful and informative elements with commercial ones (Castelló-Martínez et al., 2016; Marzal-Felici & Casero-Ripollés 2017; Vicente-Torrico, 2019). Users sometimes perform commercial tasks without knowing it, by making advertising content go viral with the appearance of entertainment or games, or it may simply be difficult for them to switch on their advertising mindset and thus respond reflectively to commercial content (Hudders et al., 2017; Feijoo & Pavez, 2019). Thus, consumerist messages are normalised, and content is consumed that was not previously classified as suitable for minors (López-Bolas et al., 2022).

To respond to this casuistry, it is necessary to act on advertising literacy from an early age, to provide users with skills that allow them to face advertising in a critical way, favouring an understanding of persuasive intentions and the activation of filters to advertising messages (Friesdad & Wright, 1994; Van-Dam & Van-Reijmersdal, 2019; Livingstone & Helsper, 2006).

Several authors have defined this literacy in three dimensions: attitudinal, which refers to the predisposition that people show for advertising content; cognitive, which is the understanding that subjects show of the advertising industry and its implications; and the third, situational or executional, which occurs at the same time as reception of advertising in a real environment and requires the activation of the two previous dimensions (Rozendaal et al., 2011; An et al., 2014; Hudders et al., 2017).

The literature on advertising literacy indicates that, despite the growing number of studies following the pandemic, empirical work is needed to help look at this topic in greater detail, particularly as pertaining to the youngest children (Fernández-Gómez et al., 2023; Arbaiza et al., 2024).

Studies on the cognitive dimension of advertising literacy in minors have traditionally focused on age. Children between 4 and 10 years of age have difficulty recognising integrated advertising that appears in influencer content or video games, as it is not marked by commercial bumpers and at those ages they have limited associative networks and therefore apply low-effort processing (An et al., 2014; Hudders et al., 2017; Feijoo et al., 2021). The study by Feijoo & Pavez (2019), for example, analyses videos from the children’s series «Soy Luna» and finds that users between the ages of 8 and 17 are not able to classify as advertising those actions that only show the benefits of products. The work of Feijoo & García (2019) shows that between 14% and 34% of users between the ages of 10 and 14 have trouble in recognising advertising on platforms such as YouTube and particularly on X (formerly Twitter), possibly due to the lower use that minors make of this social medium.

The cognitive dimension encompasses a more complete level than mere recognition, it is the ability to internalise and understand how the advertising industry works. The study by Zozaya-Durazo et al., (2022) shows that adolescents, especially from the age of 14, understand and assume that one of the functions of influencers is to sell products and services. Such unreflecting acceptance, according to the analysis by Van-Dam & Van-Reijmersdal (2019), has repercussions on the lack of activation of the attitudinal dimension of 12- to 16-year-olds, if consideration is given to the degree of acceptance, they show for the content generated by influencers and the approval of advertising content as remuneration for their work. Such attitudes are also found among university students, since as long as communication of the advertised products remains natural and maintains the influencer's tone these young people willingly accept commercial communication (De Frutos-Torres & Pastor-Rodríguez, 2021).

The last level of the cognitive dimension is materialised in the recognition of persuasive tactics in advertising, however, there is no consensus on this point in the studies. Rozendaal et al., (2010) stated that it can already be articulated from the age of 11. That same author, in a later study, concluded that it begins to be discerned from the age of 8 and continues developing until the age of 13 (Rozendaal et al., 2011). While the review work carried out by John (1999) indicated a broader age range of between 10 and 16 years of age.

Surprising results can be found regarding the recognition of advertising by minors. Loose et al., (2022) point out that although acceptable literacy levels are achieved in children aged 4 to 7, that does not mean that it is the result of reflective reasoning, but rather associative reasoning based on what they are seeing, that is, the result of chance. For example, when faced with an advertising format such as unboxing, Loose et al., (2022) report that a child selected the «buy» response not because he understood the YouTuber ’s intention to sell, but because he thought that the YouTuber had bought the product to show it on YouTube.

It is also worth mentioning some of the results found in studies that explore advertising attitudes in relation to familiarity with a stimulus, understood as any prior experience that a subject shows with one of the elements involved in the communication process. This experience translates into acceptance by an influencer’s followers that he/she is an expert in a given field, resulting in credibility for the content received, and works in favour of the intention to purchase (De Jans et al., 2018; Xiao et al., 2018). Feijoo & García-González (2019) conclude that trust is greater in those social media which users interact with most frequently (YouTube, WhatsApp, and Instagram). Sádaba & Feijoo (2022) point out that a familiar environment is created between an influencer and their audience, which leads to the latter relaxing when faced with commercial communication.

However, other authors basing themselves on selective exposure theory, postulate that knowledge of persuasion is shaped, in part, by experience with advertisements. That experience causes different attitudes and levels of selective attention to advertising, which can translate into avoidance behaviours (Friesstad & Wright, 1994; Moore & Rodgers, 2005). Moore & Rodgers (2005) confirmed this theory, though only with the regular use of newspapers, not in the rest of the media analysed (internet, television, radio, and magazines).

Another approach to advertising literacy focuses on the level of acquisition of media skills based on categories such as language, technology, production and programming, reception and audiences, ideology and values, and aesthetics (Ferrés-Prats, 2007; Ferrés-Prats & Piscitelli, 2012). The work of Marta-Lazo & Grandío (2013) within the competence of reception and audiences, focuses on the ability to decode the emotional elements of audio-visual content. The results demonstrate, on the one hand, the inability of individuals over 16 years of age to recognise the role of emotions in communicative proposals, since the participants consider that only rational arguments form part of a purchase decision, despite the fact that they were not present in the advertisement shown. On the other hand, the work of Ramírez-García et al., (2016), also on media competences, concludes that children between 9 and 10 years of age cannot be considered media competent. Only half of the subjects in their study were correct about the values conveyed by the advertising shown. García-Ruiz et al., (2014), conclude in their research with 16- and 17- year-old students that only 35.6% were able to differentiate between arguments and emotions, therefore they are not deemed capable of carrying out a comprehensive and critical reading of advertising messages.

Finally, the literature reviewed includes studies focused on classroom actions. De Jans et al., (2018) concluded, after a classroom action with young people between 11 and 14 years old, that when adolescents become more skilled at recognising influencer advertising, trust in these prescribers decreases, attitudinal literacy is activated, and purchase intention is reduced. Other studies used classroom mediation to improve critical thinking in pre-university students by working on sexist elements or the presence of inappropriate topics. The results show that after the action, students are less consenting towards this type of advertising and are more critical and even upset by the content, which they sometimes define as blackmail (Adams et al., 2017; Hernández-Santaolalla et al., 2017). Likewise, the work of Liao et al., (2016) used classroom action with children between 10 and 11 years old to improve, among other things, advertising criticism of food products. They focused on recognition, the intention to sell the advertising and the counterargument of the advertising messages. The results show that 71.4% stated that they had chosen healthier foods, without being influenced by the commercial messages.

Review of the literature shows the complexity involved in achieving effective advertising literacy and, in particular, the difficulty of working on acquiring the cognitive dimension at the actual moment of reception. Furthermore, the literature shows that recognising a format or knowing how the advertising industry works does not imply that the person knows how to apply this knowledge at the moment of receiving content, especially if that coincides with low levels of cognitive processing, such as browsing social environments with influencer content, where entertainment or enjoyment prevails (Rozendaal et al., 2011; Hudders et al., 2017; Van Dam & Van Reijmersdal, 2019; Zarouali et al., 2021). In this scenario, familiarity can be a factor inhibiting the cognitive dimension of advertising literacy by facilitating acceptance and, therefore, it is more difficult to apply analytical thinking to the persuasive process. Previous studies had already related this variable to the attitudinal dimension towards advertising (Moore & Rodgers, 2005; Xiao et al. 2018, Feijoo & García-González, 2019; among others).

Despite the diversity of studies and methodological approaches to research on this topic, major gaps remain. Fernández-Gómez et al., (2023), point out in their recent review work, that most of the studies with minors focus on a single population, ignoring the possible differences triggered by the environment, such as, for example, the subject's habitat or the familiarity between influencer and user. Both correspond to differences in the level of exposure to advertising stimuli between urban and rural populations, and between populations that vary in their connection with a given prescriber.

Therefore, the main purpose of this study is to establish to what extent the level of exposure in minors influences advertising literacy and contributes to the development of the cognitive and executional dimensions. Moreover, it represents an empirical contribution concerning the elements that need to be further studied and improved in order to carry out effective educational action.

Two research questions and three hypotheses with subsections are derived from this objective:

1. Does the level of exposure to advertising stimuli, whether due to the subject's habitat or familiarity with the source, influence the cognitive dimension of advertising literacy?

2. Does educational action improve critical reception of advertising content on social media?

Hypothesis 1. Familiarity with prescribers influences (a) recognition of persuasive tactics, (b) interpretation of the protagonists’ roles, and (c) identification of commercial actions in the moment of viewing.

Hypothesis 2. Minors educated in rural contexts develop fewer skills to confront advertising content in terms of (a) recognising persuasive tactics, (b) interpreting the role of the protagonists, and (c) identifying commercial actions in the moment of viewing.

Hypothesis 3. Educational action improves advertising literacy in terms of (a) recognition of persuasive tactics, (b) interpretation of the protagonists’ roles, and (c) identification of commercial actions in the moment of viewing.

2. Methodology

This study uses an experimental design applied to two groups, one rural and one urban, which are observed at two different times: before and after the classroom action, which took place in April-May 2022 in the urban environment and May-June 2023 in the rural area.

This is an action-research that allows participants to contribute to and transform social reality, providing autonomy and power to those who participate as subjects of the research (Latorre, 2005; Sequera, 2016). Thanks to the classroom action, participants take part in a mediation that allows them to activate nodes within their associative network to be used in future in similar situations, a key procedure in strengthening the situational dimension according to Hudders et al., (2017) or Nelson et al., (2017), among others. This associative network is described by some authors as the key to making up for the fact that advertising on social media appears without external signs that identify it as such, elements like bumpers, jingles, voice-overs, etc. (Nelson et al., 2017; Vanwesenbeeck et al., 2020; Loose et al., 2022). Other authors feel it is an advantage as it trains these minors to successfully deal with embedded advertising and its commercial intention (Van-Reijmersdal & Rozendaal, 2020; Feijoo & Fernández-Gómez, 2021).

An ad hoc questionnaire was used for data collection, administered at two different times with questions adapted to the content of the classroom action. The use of evaluated action methodology represents an opportunity to look more deeply into the scope of advertising literacy (Fernández-Gómez et al., 2023).

2.1. Procedure

The research was carried out in two phases: in the first, the working materials were prepared and in the second, the educational action took place.

First, two videos by the well-known YouTuber ElRubius were chosen, he was top of the ranking when the action was carried out (Socialblade, March 7, 2022). The choice corresponds to a subject dear to the participants: fast food and cinema, something of interest to both sexes, a key aspect for improving learning according to Jorrín-Abellán et al., (2021); the two videos are similar in duration, views, likes and advertising inserts, as can be seen in Table 1.

The content of the first video, titled: «Creating the ultimate burger» (https://tinyurl.com/y2csnur6), corresponds to the pretest. It tells the story of the creation of a burger in collaboration with Chef Dani García. It also features VEGETTA777, another well-known YouTuber. It was classified by ElRubius as an Epic Vlog, without identifying elements such as commercial communication (January 27, 2022). The second video, applied in the post-test, is about cinema and is titled: «The Tom Holland Challenge» (https://tinyurl.com/4kdsxkv4).

Table 1. Data on the materials used in the educational action

|

|

Duration in minutes |

Number of views |

Number of likes |

Advertising inserts |

|

Creating the ultimate burger |

14’49” |

5,396,264 |

783,246 |

More than 7 |

|

The Tom Holland challenge |

14’15” |

5,089,618 |

841,940 |

More than 7 |

Source: Created by the authors

The tutor’s lesson plan for the classroom was then put into practice in 4 sessions of 50 minutes over 4 consecutive weeks. In the initial session, the first ElRubius video (Creating the ultimate burger) was shown, and the first questionnaire was handed out (pre-test). In the second session, the content of the video seen in the first session was critically analysed, examining the commercial elements that appeared in it (message sender and identification of the advertising content). Also analysed were the persuasive aspects through the emotional expressions of the protagonists and how tactics of that type generate acceptance in the receptor. In the third session, the participants were organised into groups of 4 who had to critically analyse the content of an influencer chosen by them and present it in class. In the last session, the second ElRubius video (The Tom Holland Challenge) was shown, and the second questionnaire was done (post-test).

2.2. Study design and measurement variables

The design of the study sets out three independent variables: familiarity with the sender, the recipient's habitat and the educational action; and three dependent variables: recognition of persuasive elements, recognition of the advertising source and identification of advertising communication.

Familiarity with the sender. This variable is understood as any previous experience with the source and is related to the trust that users show in it (Xiao et al., 2018). It can be measured through the amount of time that users spend on a channel (Moore & Rodgers, 2005). In line with the study by De Jans et al. (2018) it was considered whether the sample regularly consumes ElRubius content. It is assumed that being familiar with more content from an influencer implies knowing him/her better and being better able to identify his/her different communicative tones. To measure this, a question with three response options was used about whether they knew the influencer: «no», «yes, but I hardly ever see their content», or «yes, I see quite a lot of their content». The responses were dichotomised for analysis: the first two were labelled as «lack of familiarity», while the third option corresponds to «familiarity».

Recipient’s habitat. Habitat can influence advertising literacy. Living in urban areas exposes the user to more advertising, urban individuals are more accustomed to this type of communication proposals and their user experience influences their recognition. Habitat is a differentiating element in the use of social media; the study by Eurona & Kantar Media (2021) places rural users behind in terms of trends, they start using the most popular social media later than other populations, and access to social media only reaches 67% of the rural population compared to 74% of the total population. This variable is configured in the present study based on where the educational action was carried out, at two sites: one urban, a high school in a provincial capital, while the other was a high school in a rural town, attended by students from villages with fewer than 5,000 inhabitants.

Recognition of persuasive elements. Persuasive tactics are subtle practices that help convince the receiver about the characteristic to be communicated. Among these elements is the protagonists’ spontaneity and the resources used to improve and idealise the product (Rozendaal et al., 2011). In this case, the persuasive practice is marked by any emotional components that the protagonists show in their participation. Two different questions were used to measure this variable, one in the pre-test that alluded to the gestures with which ElRubius and his friends expressed how good the hamburger was, and a second about the influencer’s gestures of emotion and surprise, although in reality it was part of the script. Quantification of the response took the form of correct or incorrect.

Recognition of the source or sender of the advertisement. This variable is essential to be able to activate filters on the content received. To measure this question, the identification of the role played by ElRubius within the video was considered. Among the response options there was a correct one which was «guest» and two others that were incorrect: «organiser» and «none of these options».

Identification of commercial communication. This is aimed at recognising the brands in the videos. Two questions were used about brand recognition of two products that appear advertised through passive product placement; in the first video, a Mooncler cap appears and in the second, a Hyundai car. Both brands appear subtly located on the periphery as suggested by the study by Boerman et al., (2018). Regarding the second question, used only in the third hypothesis, it is a generic question that allows us to know if the user correctly categorises the content they have just seen. The response options are: «informative», «entertaining», «funny», «commercial», and «I don’t know».

2.3. Sample

The sample was selected ad-hoc in two secondary education centres located in an urban and a rural area respectively, which voluntarily agreed to participate in the action. The final sample consisted of 62 subjects between 12 and 16 years of age, of which 37.1% declared themselves to be male, 50% female and 12.9% preferred not to specify. 51.6% live in an urban area and 48.4% in rural zones, with populations of fewer than 5,000 inhabitants

3. Results

In this section, the three research hypotheses on advertising literacy are tested, based on familiarity, the participants’ habitat and the effectiveness of the educational action.

3.1. Variables that influence advertising literacy

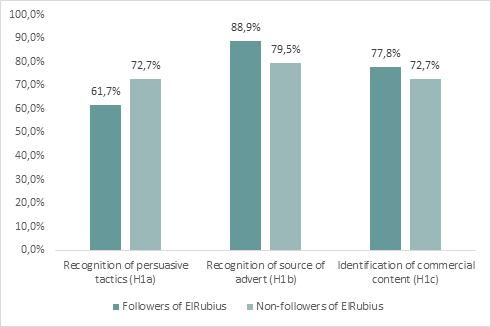

For the first hypothesis, which tests whether familiarity with the prescriber influences cognitive elements of advertising literacy, the responses were compared between subjects who said they regularly watched ElRubius content and those who did not (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comparison of cognitive abilities between followers and non-followers of ElRubius (Hypothesis 1)

Source: Created by the authors

The results indicate that 61.7% of those who reported watching ElRubius content were correct in recognising persuasive tactics (H1a), compared to 72.7% of those who did not regularly follow the influencer. Comparison of the statistics using Chi-squared distribution for a confidence level of 95% does not show statistically significant differences linked to familiarity with the prescriber (Chi-squared = .811; p = .368).

Regarding the identification of the role played by each protagonist (H1b), 88.9% of those who regularly interact with the influencer correctly identified the role he was playing compared to 79.5% among those who did not follow him. Again, the comparison does not show statistically significant differences between the two groups (Chi-squared = .764; p = .382). Finally, 77.8% of ElRubius' followers correctly recognised the brands present in the video (H1c) compared to 72.7% among users who do not follow him. The differences between the two groups are not statistically significant (Chi-squared = .170; p = .680). Therefore, the first hypothesis of the study concerning the effect of familiarity with the influencers on the assessment of advertising literacy cannot be validated. However, it is worth noting that there is a trend among the influencer's regular followers who display greater difficulty when it comes to recognising persuasive tactics, which could be indicative of the fact that being accustomed to a prescriber's communication language makes it difficult to activate the cognitive dimension corresponding to advertising literacy.

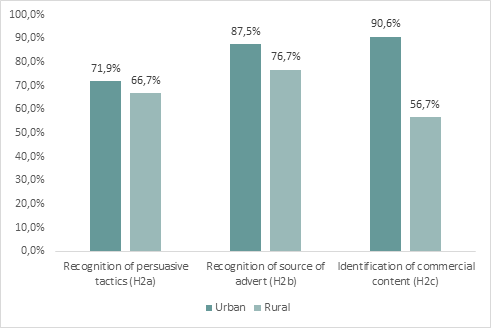

The second hypothesis analyses the level of the same elements as the previous hypothesis but based on the participant's habitat: rural or urban (Figure 2). The analysis shows that 71.9% of urban participants correctly recognised ElRubius' persuasive tactics (H2a) compared to 66.7% of those who live in a rural area. The Chi-squared test yields a figure of 0.198 (p = .657) in the recognition of persuasive tactics, therefore, there are no statistically significant differences by habitat.

Figure 2. Comparison of cognitive abilities of rural and urban populations (Hypothesis 2)

Source: Created by the authors

Regarding interpretation of the protagonist’s role (H2b), 87.5% of the subjects living in an urban environment were correct, compared to 76.7% of those living in a rural environment. The contrast does not reach statistically significant differences (Chi-Squared = 1.245; p = .264), consequently, there are no differences between the two groups in correctly identifying the role of ElRubius.

Regarding the identification of commercial content (H2c), 90.6% of the urban sample got it right compared to 56.7% of the rural sample. In this case, the differences are statistically significant (Chi-Squared = 9.326; p = .002). Urban participants are better at recognising commercial content than those who grow up in rural areas.

3.2. Classroom action as a process toward advertising literacy

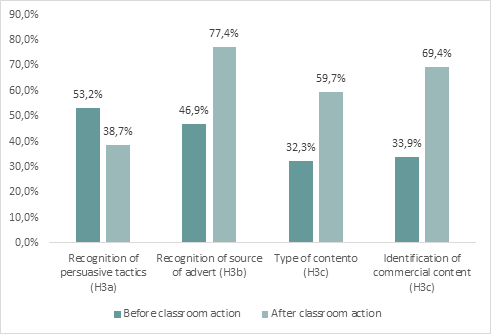

The third hypothesis utilises three parameters to analyse the extent to which the educational action has improved advertising literacy. To test the first, the recognition of persuasive tactics (H3a), the percentage of subjects who correctly identified the protagonists’ actions is compared. The results indicate that after the educational action, 38.7% of the subjects correctly recognised the reaction compared to 53.2% of the subjects who correctly identified it before the action. Therefore, the action has not had the expected result in improving the recognition of persuasive tactics.

The role ElRubius plays in the video is the next aspect to be tested (H3b). The comparison shows that 77.4% of responses after the classroom action are correct compared to 46.9% of the subjects who understood in the pre-test that the influencer acted as a guest and not as an organiser (sender of the advertising content). The McNemar test has been applied here to check if there are significant differences in the figures, this test being recommended for samples related to dichotomous responses (Sierra-Bravo, 2003). The figure for associated probability is .000, therefore it can be affirmed with 99% confidence that classroom action improves understanding of the role that influencers play in social media.

Finally, the third hypothesis analyses whether the sample is able to better identify commercial actions in the moment of viewing (H3c). Two items are used to contrast this: the categorisation of the content as entertainment or commercial, and the number of recognised brands that appear during viewing. The results indicate that the participants increased their commercial identification of the communication after the action, going from 32.3% in the pre-test to 59.7% in the post-test (Figure 3). Thus, entertainment was no longer the predominant response.

Figure 3. Developments in the cognitive elements of advertising literacy after the action (Hypothesis 3)

Source: Created by the authors

The statistical contrast, carried out by means of the McNemar test for dichotomous variables, yields a probability of .000; consequently, it can be stated that the action improved reflection on the type of content that the sample was watching. In addition, 69.4% correctly identified the brands that appeared in the video compared to 33.9% of correct answers before the support in the classroom. The McNemar test is used again, with a significance of .000 indicating that there are statistically significant differences, which confirms H3c.

Overall, the third hypothesis is partially confirmed, as improvements have been achieved in understanding the role played by the main influencer and in the correct identification of commercial content, but there has been no improvement in the recognition of persuasive tactics.

4. Discussion

The results of this research, in addition to answering the research questions, open up avenues for further research into advertising literacy in minors.

Familiarity, that is, being familiar with the interlocutor, does not influence the recognition of narrative tips that they employ to achieve a communication objective, which may be commercial or of another nature; ideological, lifestyle, etc. It may be that the acceptance of the influencers' discourse regardless of the content launched makes the receivers’ analytical exercise difficult, as Xiao et al., (2018) point out. Furthermore, previous studies conclude that the appearance of disordered advertising and integrated advertising tactics hinders advertising being instructive through experience, an aspect that has been found on television and even on web pages (Hudders et al., 2017; Kennedy et al., 2019).

The results on habitat lead to the conclusion that deeper consideration of this variable is called for, as it has been little analysed until now. However, it has been shown that users who are more accustomed to receiving advertising in the media have a better chance of recognising commercial proposals. Consequently, residents of rural environments are, to some extent, at a disadvantage when detecting advertising and activating cognitive mechanisms in the face of persuasive attempts. For future actions on advertising literacy, it is advisable to consider the degree of exposure to commercial content due to its importance in acquiring this competence.

The study also reveals that educational action is useful for activating elements of advertising literacy that may be considered redundant, that is, that are associated with specific patterns. For example, the fact that advertising elements are introduced within content supposedly intended for entertainment moves subjects to associate it with commercial content and stop categorising it as leisure. That facilitates the activation of certain psychological barriers to the acceptance of the content being viewed and may act as a brake on its unconscious commercial re-dissemination. However, educational action on persuasive tactics is insufficient. Advertising narratives are diverse and ensuring that users are able to recognise them requires greater awareness of the type of resources commonly used in advertising language. It is a type of knowledge that is acquired over time and with maturity; in other words, it is a learning exercise that requires guided practice.

In short, this study opens up new avenues of research that were called for by other studies such as Veirman et al., (2019) or Feijoo & García-González (2019) to empower minors in the face of advertising narratives. It is worth noting the differential nature of communication through influencers in advertising literacy and the importance of user maturity in the face of this fact. Ultimately, education about advertising and the acquisition of skills will be the main path to enfranchisement.

Carrying out effective action calls for learning to take place over time, introducing real cases that aid understanding, but also general material that addresses a wider type of case studies. The most basic cognitive competence by which content is categorised as advertising can be easily integrated into educational practices. Advertising strategies and tactics have been shown to be more complex and require an approach that takes into account the emotional components of communication. That is an issue that must continue to be worked on with an action-based approach. It is important to adapt to the context of the individual who is the subject of the action, which implies having some prior reference about their advertising experience, just as is done in formal learning, in which a pre-assessment is carried out to assess the level of knowledge from which one starts.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the limitations of this study. This is an example of action research that is limited to a single literacy action, therefore, it would be desirable to extend the model to other cases to confirm the results found, to advance in the role of variables such as familiarity that has not been confirmed, and to approach it over a longer period of time.

Ethics and Transparency

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their suggestions, which have undoubtedly contributed to the improvement of the manuscript.

Financing

This research has been carried out within the RDI Project PID 2019-104689RB100 “INTERNETICS Truth and ethics in social networks. Perceptions and educational influences of minors on Twitter, Instagram and YouTube”. And has received financial support from the GIR Comunicación Audiovisual e Hiperme-dia (GICAVH) of the UVa.

Conflicts of interest

The authors hereby declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Authors' contributions

|

Function |

Author 1 |

Author 2 |

Author 3 |

Author 4 |

|

Conceptualisation |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Data curation |

X |

|

|

|

|

Formal analysis |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Acquisition of financing |

|

|

|

|

|

Research |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Methodology |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Project Management |

|

|

|

|

|

Resources |

|

|

|

|

|

Software |

|

|

|

|

|

Supervision |

|

X |

|

|

|

Validation |

|

|

|

|

|

Display |

|

|

|

|

|

Writing - original draft |

X |

|

|

|

|

Writing - review and editing |

|

X |

|

|

Access to data

The possibility exists of accessing the database and the questionnaire through a permanent URL.

Bibliographical references

Adams, B., Schellens, T. & Valcke, M. (2017). Fomentando la alfabetización ética de los adolescentes en publicidad en Educación Secundaria. Comunicar, 52, 93-103. https://doi.org/10.3916/C52-2017-09

AIMC (2024). Navegantes en la Red (nº26). AIMC

An, S., Jin, H. S. & Park, E. H. (2014). Children’s Advertising Literacy for Advergames: Perception of the Game as Advertising. Journal of Advertising, 43(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2013.795123

Arbaiza, F., Robledo-Dioses, K. & Lamarca, G. (2024). Alfabetización publicitaria: 30 años en Estudios Científicos. Comunicar, 78, 166-178. https://doi.org/10.58262/V32I78.14

Boerman, S., Van Rejimersdal, E. A., Rozendaal, E. & Dima, A. L. (2018). Development of the Persuasion Knowledge Scales of Sponsored Content (PKS-SC). International Journal of Advertising. The Review of Marketing Communications, 37(5), 671-697. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2018.1470485

Casaló, L. V. & Escario, J.J. (2019). Predictors of excessive internet use among adolescents in Spain: The relevance of the relationship between parents and their children. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 344–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.042

Castelló-Martínez, A., Del Pino Romero, C. & Tur Viñes, V. (2016). Estrategias de contenido con famosos en marcas dirigidas a público adolescente. Icono 14, 14, 123-154. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v14i1.883

Dans-Álvarez-de-Sotomayor, I., Múñoz-Carril, P.C. & González Sanmamed, M. (2021). Hábitos de uso de las redes sociales en la adolescencia: desafíos educativos. Revista Fuentes, 23(3), 280-295. https://doi.org/10.12795/revistafuentes.2021.15691

De-Frutos-Torres, B. & Pastor-Rodríguez, A. (2021). ¿Seguimos confiando en las redes sociales? Un estudio sobre la valoración de las redes y su publicidad. En J. Sierra Sánchez, y A. Barrientos Báez (eds.) Cosmovisión de la comunicación en redes sociales en la era postdigital (pp. 1141-1158). Mc Graw Hill

De-Frutos-Torres, B., Collado-Alonso, R. & García-Matilla, A. (2020). El coste del smartphone entre los profesionales de la comunicación: análisis de las consecuencias sociales, laborales y personales. Revista Mediterránea De Comunicación, 11(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2020.11.1.9

De-Jans, S., Cauberghe, V. & Hudders, L. (2018). How an Advertising Disclosure Alerts Young Adolescents to Sponsored Vlogs: The Moderating Role of a Peer-Based Advertising Literacy Intervention through an Informational Vlog. Journal of Advertising, 47(4), 309-325. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2018.1539363

Eurona & Kantar Media (2021). Cómo la España vaciada llena su tiempo en internet. El primer informe sobre el consumo de Internet en la España rural. https://tinyurl.com/bdftd3r3

Feijoo B. & García-González, A. (2019). Publicidad y entretenimiento en los soportes online. youtubers como embajadores de marca a través del estudio de caso de makiman131. Perspectivas De La Comunicación, 13(1), 133–154. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48672020000100133

Feijoo, B. & Fernández-Gómez, E. (2021). Niños y niñas influyentes en YouTube e Instagram: contenidos y presencia de marcas durante el confinamiento. Cuadernos.info, 49, 300-328 https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.49.27309

Feijoo, B. & García, A. (2019). Actitud del menor ante la publicidad que recibe a través de los dispositivos móviles. AdComunica, 18, 199-218. https://doi.org/10.6035/2174-0992.2019.18.10

Feijoo, B. & Pavez, I. (2019). Contenido audiovisual con intención publicitaria en vídeos infantiles en YouTube: el caso de la serie Soy Luna. Palabras clave, 32(1), 313-331. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.32.37835

Feijoo, B., Bugueño, S., Sádaba, C. & García-González, A. (2021). La percepción de padres e hijos chilenos sobre la publicidad en redes sociales. Comunicar, 67(2). https://doi.org/10.3916/C67-2021-08

Fernández-Gómez, E., Segarra-Saavedra, J. & Feijoo, B. (2023). Alfabetización publicitaria y menores. Revisión bibliográfica a partir de la Web of Science (WOS) y Scopus (2010-2022). Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 81, 1-23. https://www.doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2023-1892

Ferrés-Prats, J. (2007). La competencia en comunicación audiovisual: propuesta articulada de dimensiones e indicadores. Comunicar, 29, 100-107. https://doi.org/10.3916/C29-2007-14

Ferrés-Prats, J. & Piscitelli, A. (2012). La competencia mediática: propuesta articulada de dimensiones e indicadores. Comunicar, 38(29), 75-82. https://doi.org/10.3916/C38-2012-02-08

Friestad, M. & Wright, P. (1994). The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. Journal of consumer research, 21(1), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.1086/209380

García-Ruiz, R., Ramírez-García, A. & Rodríguez-Rosell, M. (2014). Educación en alfabetización mediática para una nueva ciudadanía prosumidora. Comunicar, 43, 15-23. https://doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-01

GFK (2021). Estudio Mobile & Conectividad Inteligente 2021. IAB Spain. https://tinyurl.com/3ucj6rk9

GFK & nPeople (2019). Estudio anual de mobile & connected devices. IAB. https://iabspain.es/estudio/estudio-anual-de-mobile-connected-devices/

Hernández-Santaolalla, V., Silva-Vera,F. & Meandro-Fraile, E. (2017). Alfabetización mediática y discurso publicitario en tres centros escolares de Guayaquil. Convergencia, 24(74). https://doi.org/10.29101/crcs.v0i74.4388

Hudders, L., De Pauw, P., Cauberghe, V., Panic, K., Zarouali, B. & Rozendaal, E. (2017). Shedding New Light on How Advertising Literacy Can Affect Children's Processing of Embedded Advertising Formats: A Future Research Agenda. Journal of Advertising, 46(2), 333-349. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1269303

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2024). Uso de productos TIC por los niños de 10 a 15 años. INE. https://tinyurl.com/29nc2jjd

John, D. R. (1999). Consumer socialization of children: a retrospective look at twenty-five years of research. Journal of Consumer Research, 26 (3), 183-213. https://doi.org/10.1086/209559

Jorrín-Abellán, I. M., Fontana-Abad, M. & Rubia-Avi, B. (2021) Investigar en Educación. Síntesis

Kennedy, A.M., Jones, K. & Williams, J. (2019). Children as Vulnerable Consumers in Online Environments. The journal of consumer affairs, 53(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12253

Latorre, A. (2005). La investigación-acción. Conocer y cambiar la práctica educativa (3ª ed.). GRAO

Liao, L. L., Lai, I. L., Chang L. C. & Lee, C. K. (2016). Effects of a food advertising literacy intervention on Taiwanese children's food purchasing behaviors. Health Education Research, 31(4), 509–520. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyw025

Livingstone, S. & Helsper, E. J. (2006). Does advertising literacy mediate the effects of advertising on children? A critical examination of two linked research literatures in relation to obesity and food choice. Journal of Communication, 56, 560–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00301.x

Loose, F., Hudders, L., De-Jans, S. & Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2022). A Qualitative Approach to Unravel Young Children’s Advertising Literacy for YouTube Advertising: In-Depth Interviews with Children and their Parents. Young Consumers, 24(1), 74-94. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-04-2022-1507

López- Bolas, A., Neira-Placer, P., Visiers-Elizaicin, A. & Feijoó-Fernández, B. (2023). Incitación al consumo de juguetes a través de youtubers infantiles. Estudio de caso. index.comunicación, 12(2), 251-275. https://doi.org/10.33732/ixc/12/02Incita

Marta-Lazo, C.M. & Grandío, M. (2013). Análisis de la competencia audiovisual de la ciudadanía española en la diimensión de recepción y audiencia. Communication&Society/Comunicación y Sociedad, 26(2), 114‐130. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.26.36129

Marzal-Felici, J. & Casero-Ripollés, A. (2017). El discurso publicitario: núcleo de la comunicación transmedia. AdComunica, 14, 11-19. https://doi.org/10.6035/2174-0992.2017.14.1

Moore, J. & Rodgers, S. (2005). An examination of advertising credibility and scepticism in five different media using the persuasion knowledge model Attention, Attitude and Experience as Predictors of Advertising Avoidance Behaviors Among Five Different Media. En Proceedings of the 2005 conference of the American Academy of Advertising, 10-18.

Navarro, N. (2017). El suicidio en jóvenes en España: cifras y posibles causas. Análisis de los últimos datos disponibles. Clínica y Salud, 28(1), 25-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clysa.2016.11.002

Nelson, M. R., Atkinson, L., Rademacher, M. A. & Ahn, R. (2017). How Media and Family Build Children's Persuasion Knowledge. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 38(2), 165-183. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2017.1291383

Orosco, J. R. y Pomasunco, R. (2020). Adolescentes frente a los riesgos en el uso de las TIC. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 22(17), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2020.22.e17.2298

Padilla, S., Ortiz, E.R., Álvarez, M., Castaño, A. T., Perdomo, A. S., & López, M.J.R. (2015). La influencia del escenario educativo familiar en el uso de Internet en los niños de primaria y secundaria. Infancia y aprendizaje. Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 38(2), 402-434. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2015.1016749

Plokiko (1 de enero de 2018). Los 11 momentos que han marcado el sector móvil en España desde el encendido del 3G. Xatakamovil. https://tinyurl.com/ykrh5bjm

Qustodio (2023). Nacer en la era digital. Generación IA. Informe anual Qustodio. https://tinyurl.com/ykrh5bjm

Ramírez-García, A., Sánchez-Carrero, J. & Contreras-Pulido, P. (2016). La competencia mediática en educación primaria en el contexto español. Educ. Pesqui., 42(2), 375-394. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-9702201606143127

Rial, A., Golpe, S., Isorna, M. Braña, T. & Gómez, P. (2018). Minors and problematic Internet use: Evidence for better prevention. Computers in Human Behavior 87, 140-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.030

Rozendaal, E., Buijzen, M. & Valkenburg, P. M. (2010). Comparing children’s and adults’ cognitive advertising competences in the Netherlands. Journal of Children and Media, 4, 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482790903407333

Rozendaal, E., Lapierre, M. A., Van Reijmersdal, E. A. & Buijzen, M. (2011). Reconsidering Advertising Literacy as a Defense Against Advertising Effects. Media Psychology, 14(4), 333-354. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2011.620540

Sádaba, C., & Feijoo, B. (2022). Atraer a los menores con entretenimiento: nuevas formas de comunicación de marca en el móvil. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 13(1), 79-91. https://www.doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM.20568

Saraf, V., Jain, N.C., & Singhai, M. (2013). Children and parents’ interest in tv advertisements: Elucidating the persuasive intent of advertisements. Indian Journal of Marketing, 43(7), 30-30. https://doi.org/10.17010/ijom/2013/v43/i7/34016

Sequera, M. (2016). Investigación-acción: un método de investigación educativa para la sociedad actual. Revista Arjé de Posgrado FaCE-UC, 10(18). https://tinyurl.com/2dpewmjz

Sierra-Bravo, R. (2003). Técnicas de investigación Social teoría y ejercicios. Thomson.

Smahel, D., Machackova, H., Mascheroni, G., Dedkova, L., Staksrud, E., Ólafsson, K., Livingstone, S. & Hasebrink, U. (2020). EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries. EU Kids Online. https://doi.org/10.21953/lse.47fdeqj01ofo

Socialblade (7 de marzo de 2022). Top 100 youtubers en España ordenados por suscriptores. Socialblade

Suárez-Álvarez, R., De-Frutos-Torres, B. & Vázquez-Barrio, T. (2020). La confianza hacia el medio interactivo de los padres y su papel inhibidor en el control de acceso a las pantallas de los menores. Zer, 25(49), 13-31. https://doi.org/10.1387/zer.21349

Van-Dam, S. & Van-Reijmersdal, E A (2019). Insights in Adolescents’ Advertising Literacy, Perceptions and Responses Regarding Sponsored Influencer Videos and Disclosures. Cyberpsychology. Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 13(2). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2019-2-2

Van-Reijmersdal, E.A. & Rozendaal, E. (2020). Transparency of digital native and embedded advertising: Opportunities and challenges for regulation and education. The European Journal of Communication Research, 45(3), 378-388. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2019-0120

Vanwesenbeeck, I., Hudders, L. & Ponnet, K. (2020). Understanding the YouTube Generation: How Preschoolers Process Television and YouTube Advertising. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(6). https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0488

Veirman, M., Hudders, L. & Nelson, M. R. (2019). What Is Influencer Marketing and How Does It Target Children? A Review and Direction for Future Research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02685

Velasco, A. & Gil, V. (2017). La adicción a la pornografía: causas y consecuencias. Drugs and Addictive Behavior, 2(1), 122-130. https://doi.org/10.21501/24631779.2265

Vicente-Torrico, D. (2019). Nuevas herramientas, viejas costumbres. El Contenido Generado por los Usuarios sobre el cambio climático en YouTube. Ámbitos revista internacional de comunicación, 46, 28-47. https://doi.org/10.12795/Ambitos.2019.i46.03

Xiao, M., Wang R. & Chan-Olmsted, S. (2018). Factors affecting YouTube influencer marketing credibility: a heuristic-systematic model. Journal of Media Business Studies, 15(4), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2018.1501146

Zarouali, B., Poels, K., Ponnet, K. & Walrave, M. (2021). The influence of a descriptive norm label on adolescents' persuasion knowledge and privacy-protective behavior on social networking sites. Communication Monographs, 88(1), 5-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2020.1809686

Zozaya-Durazo, L. D., Feijoo-Fernández, B. & Sádaba-Chalezquer, C. (2022). Análisis de la capacidad de menores en España para reconocer los contenidos comerciales publicados por influencers. Revista de Comunicación, 21(2), 307-319. https://doi.org/10.26441/RC21.2-2022-A15