index●comunicación

Revista científica de comunicación aplicada

nº 15(1) 2025 | Pages 31-50

e-ISSN: 2174-1859 | ISSN: 2444-3239

Advertising and Adolescence: An Ethnographic Study of a Virtual Community

Publicidad y adolescencia. Estudio etnográfico

de una comunidad virtual

Received on 09/09/2024 | Accepted on 21/11/2024 | Published on 15/01/2025

https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/15/01Public

Isabel Rodrigo-Martín | Universidad de Valladolid

isabel.rodrigo@uva.es | https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8349-5093

Luis Rodrigo-Martín | Universidad de Valladolid

luis.rodrigo@uva.es | https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0580-9856

Daniel Muñoz-Sastre | Universidad de Valladolid

daniel.munoz.sastre@uva.es | https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1136-5289

Abstract: The object of study of this research is to analyze the main characteristics of adolescents from 12 to 16 years old, students of Compulsory Secondary Education as the target audience of various advertising campaigns. To this end, a virtual community has been created among students, with the intention of exploring the different levels of acceptance or rejection of different advertising issues, both from the creation of content to the representation of adolescence in advertising formats. The research uses a mixed methodology based on three pillars: digital ethnography, observation and survey. The results obtained will provide an accurate description of the characteristics, motivations, attitudes and concerns of adolescents and the relationship they establish with technology and with the creation of content, as well as contributing to the necessary advertising literacy.

Keywords: Digital Communication; Advertising; Teenagers; Virtual Community; Brands.

Resumen: El objeto de estudio de esta investigación consiste en conocer las principales características de los adolescentes de 12 a 16 años, estudiantes de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria, como público objetivo de diferentes campañas publicitarias. Con ese fin, se ha creado entre los estudiantes una comunidad virtual con la intención de explorar los diferentes niveles de aceptación o rechazo de las distintas cuestiones publicitarias, desde la creación de contenidos hasta la representación de la adolescencia en los formatos publicitarios. La investigación utiliza una metodología de tipo mixto basada en tres pilares: la etnografía digital, la observación y la encuesta. Los resultados obtenidos nos van a permitir trazar una descripción minuciosa de las características, motivaciones, actitudes e inquietudes de los adolescentes y la relación que establecen con la tecnología y con la creación de contenidos, así como contribuir a la necesaria alfabetización publicitaria.

Palabras clave: comunicación digital; publicidad; adolescentes; comunidad virtual; marcas.

To quote this work: Rodrigo-Martín, I., Rodrigo-Martín, L. & Muñoz-Sastre, D. (2025). Advertising and Adolescence: An Ethnographic Study of a Virtual Community. index.comunicación, 15(1), 31–50. https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/15/01Public

1. Introduction

The development and generalization of Information Technologies and Communications in the most recent years is a fact that has changed ways of being and relating in society today.

As university professors, our academic obligation requires us to attempt to respond to the needs of a student body immersed in a digital society that is constantly changing, facilitating that everyone, independent of their circumstances and capacities, can access the innumerable opportunities that these technologies afford in a responsible and constructive way. Media literacy may seem like a basic solution in order to help adolescents to develop strategies that permit them to logically disentangle digital webs as long as advertising continues to saturate social media content and to contribute decisively to the construction not only of identity and personality, but also to the perception of reality, the world, and culture. For this reason, the present study «Advertising and Adolescence» situates us within the concrete reality of the uses and customs that adolescents (the object of our study) make of these technologies and their relationship with the different communicative formulas of advertising nature. The data of the present study are especially directed toward families, institutions, businesses, and society at large, and their ultimate purpose is to contribute to digital literacy in general and to publicity in particular so that digital technologies might be a powerful tool that contributes to the integral development of Spanish adolescents.

It goes without question that advertising communication carries a specific and significant weight, as much in the development of models as in the construction of messages, and that it significantly influences the publics to which ads are directed. As such, our work is framed in the group of adolescents whom we seek to understand the relationship they establish with publicity and with brands, their acceptance or rejection of advertising formats, with the goal of using this knowledge to develop basic competencies that allow them to thoughtfully decode them in their lives now and in the future, improving their level of comprehension and their capacity to critically interpret advertising content in digital media.

2. Theoretical Framework

Our study is comprised of secondary school students, ranging in age from 12 to 16 years old, within the age of adolescence, which is the life stage between ages 10 through 19 years old (OMS), a period of transition between childhood and adulthood (Souto-Kustrín, 2007).

In this stage, various types of changes occur, including physiological (stimulation and functioning of organs with masculine and feminine hormones), structural (anatomical), psychological (personality integration and identity), as well as adaptation to social and cultural changes.

Adolescence is considered the life stage characterized by rebellion, intergenerational conflict (Bauman, 2007), and incomprehensible changes, but it is also considered the stage of numerous opportunities that we must know how to process adequately in order to help adolescents in their development process. The general characteristics of adolescence are self-esteem, search for friends, falling in love, relationships with parents and other adults, and the beginning of social relationships.

There are many tasks that adolescents must confront in order to reach adulthood with proper emotional regulation and with an enriching relationship with themselves and with the people with whom they share their spaces and time. The study of adolescents and their relationship with media communications and technology has generated significant interest among researchers from the beginning of the Twentieth Century. In 1930, in the United States, the first studies arose of infants and adolescents and their relationships to radio and film. In 1950, this research extended to television, and in 1990, they expanded again to include Information Technology (ITC).

From the turn of the past century, the media and technologies available to adolescents has increased with other information technologies likely to contain advertising (Bringé-Sala & Sádaba-Chalezquer, 2009) in different formats such as computers, the internet, mobile phones, etc. (Sádaba & Feijoo, 2022). Such technologies offer users many possibilities, with both positive and negative implications (Beck, 2008), and they produce as much uncertainty in the family institution as in different public organisms.

If information technologies create such uncertainty with respect to the risks and opportunities that they offer to the user, this situation is made even more serious with regard to adolescents because of the unique characteristics of this evolutionary stage in constant flux. For this reason, it is necessary to pay attention to the scientific literature on digital literacy from a citizen’s perspective as a critical consumer. Particularly relevant for the contextualization of our research are studies centered on advertising literacy (Murray, 2012) and those on the transition from childhood to adolescence (Núñez-Gómez et al., 2015). In this same vein, it is prudent to point out that the studies on the need for literacy specifically in minors, who by nature constitute a more vulnerable public, are incipient but summarily interesting (Fernández-Gómez et al., 2023). The majority of studies on adolescents as media and technology consumers have traditionally been propelled by an educational and protective spirit (Cárdenas-García & Cáceres-Mesa, 2019). As Livingstone explains: «It has always been characteristic of children’s and New Media research that the political agenda guides the academic agenda, at least in the first few years» (2003: 150).

This affirmation leads us to prove how studies on these questions have been proposed by public institutions (European Commission) or by other non-profit organizations (Pew Internet and American Life Project in the United States) or by distinct business sectors, of which Telefónica’s Interactive Generations Forum stands out.

Many studies have been undertaken in the United States: The Kaisen Foundation, 2005; Pew Internet and American Life Project, with studies focused on adolescents (Lenhart, 2005; Macgill, 2007; Lenhart & Madden, 2007; Jones & Fox, 2009).

In the European sphere, Livingstone & Haddan’s (2009) study of the use that youths in the then 21 European Union member states made of the internet and information technologies. This study focuses on the review of existing research in Europe about these themes, and it allowed them to identify the situation in each country and the principal consumption traits of ITC on the part of children and adolescents, as much as the risks and opportunities that they currently produce.

In Spain, the panorama of research studies into the field of adolescence and their relationship with media and information technologies display certain gaps. They have mainly been directed toward an adult-age public and have paid little attention to adolescents as a life stage that presents special characteristics. Nothwithstanding, studies do exist, like those carried out in the general field of information technology by the National Observatory of Telecommunications and the Society of Information (ONTSI), by Red.es, and others more focused on a child and adolescent public. Specifically, the 2005 Report on Childhood and Adolescence in the Society of Information, perhaps one of the most important studies realized up to the present moment, which presents the technological equipment in Spanish households and information on consumer habits of different screens, as much by children and adolescents as by adults. Furthermore, The National Institute of Youth (Injuve, 2007) also carries out studies that cover a broader age group, from 15 to 29. An example of Injuve research is the 2007 study on the use of ICE, leisure, and free time. The database and bibliographical repertoire about youth and communications media by Alcoceba-Hernando & Cadilla-Baz (2007) is of great value to future researchers, given that it provides data and sources about the analyzed public. It makes sense to highlight Garitaonandia & Garmendia’s (2007) Spanish study centered on internet use. This study is a work of mixed character that, through group dynamics of youths between ages 12 and 17, obtained information about the attitudes, habits, competencies, and behaviors surrounding this tool, as much as the risks to which they are subject when navigating the internet. The Association for Research of Media Communications (AIMC) offers, through their General Media Studies (EGM), statistics about the audiences of different Spanish communications media, and, has for years been carrying out research focusing on young audiences. Valor & Sieber’s (2004) study offers significant data about the use and attitude toward the internet and mobile phone from 14 to 22 year-olds. Lastly, we have also extracted interesting data from the National Observatory of Telecommunications and the Society of Information (ONTSI).

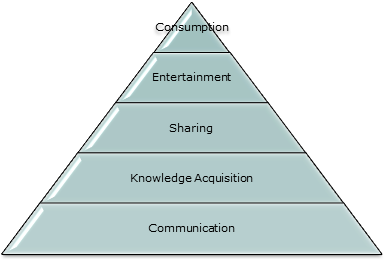

Adolescent internet users engage in a diverse and global utilization of the many possibilities offered by the internet. However, their usage preferences are hierarchically organized into four categories that reflect the pursuit of specific goals aligned with the nature of adolescents. In other words, internet browsing involves the following activities (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dimensions of Internet Use

Source: Interactive Generation in Spain, 2009.

1. Communication: Social interaction emerges as the primary purpose.

2. Knowledge Acquisition: The internet constitutes the most powerful information medium humanity has ever known. Seven out of ten respondents acknowledge using the internet to download music, movies, software, etc.

3. Sharing: The internet serves as a fundamental relational tool. The adolescent internet user, in addition to being a receiver and medium, simultaneously becomes a content emitter. Notably, 56 % of adolescents report using this service to share photos and videos with friends and peers through platforms like YouTube, 25 % use blogs, and 33 % use photoblogs to share content.

4. Entertainment: The multifaceted reality of the internet reveals one of its most attractive aspects for adolescents: the recreational component. This includes online games, racing games, sports strategies, and role-playing games. The internet provides leisure moments as a support for television and digital radio use. However, for this generation of adolescents, such usage is infrequent, with only 15 % for television and 8 % for radio.

5. Consumption: The internet serves as a platform for acquiring or selling a multitude of products or services. This activity is infrequent among adolescents, as it requires commercial transactions over the internet. Nevertheless, despite these conditions, 8 % of adolescents use the internet for shopping.

6. There is justified concern among families and educators about the excessive use of screens at these ages, which translates into a lack of attention to school tasks, memory loss, and significant irritability that hinders coexistence and personal relationships. This situation leads us to propose family models and educational methodologies that help address this developmental stage (Cataldi & Dominighini, 2015), debunking many misconceptions and erroneous ideas, enabling quality education in this digital era so that, grounded in firmness and freedom, the use of screens by current adolescents can be trusted and controlled.

7. Finally, regarding the field of advertising communication and its relationship with adolescents, we are primarily interested in focusing on the role adolescents play in and their relationship with social networks (Van-Reijmersdal et al., 2020), in their dual roles as emitters and generators of content (Espiritusanto-Nicolás, 2016) and as receivers of it (Zozaya et al., 2022). Another perspective to consider is the use of underage adolescents in network content generated by adults for advertising purposes (Van-den-Abeele et al., 2024). The dominance of content consumption generated on social networks conditions companies and brands to focus on the world of social networks and to gradually abandon the use of traditional media (Lara & Ortega-Chacón, 2016) in favor of building influencers and social media stars (Hudders et al., 2021), some of digital nature (Rodrigo-Martín et al., 2021), the influence of which on adolescents requires deep reflection (Hudders & Lou, 2022).

8. Given the need to connect with adolescents, consumer brands construct digital identities (Tafesse & Wood, 2021) that avoid traditional media and opt for the creation of brand content in digital media (Saavedra-Llamas et al., 2020). All this strongly confirms the need for education in communicative and digital competencies and to undertake the profound labor of increasing communicative literacy.

3. Objectives

General Objective:

– To assess the level of acceptance of advertising communication and various types of content generated by brands for adolescents.

Specific Objectives:

– To determine the level of acceptance of advertising communication based on the medium and format used to reach adolescents.

– To more precisely define the motivations, interests, and needs of current adolescents.

– To understand the evaluation of different communicative proposals.

– To provide secondary education teachers with tools and activities that enable them to effectively teach advertising communication, thereby promoting advertising literacy among their students.

– To analyze the originality and creativity of new communicative formats created by the adolescents participating in the study.

4. Methodology

Our research employs a mixed-methods approach, based on the triangulation of three different but complementary instruments: digital ethnography, observation, and surveys.

Firstly, it is framed within the context of digital ethnography as described by Pink et al., (2019). This digital ethnography is not merely a logical and natural evolution of traditional ethnography. It is a research method that allows us to address the new realities emerging in virtual worlds. The contributions of digital ethnography reveal the various cultural realities that arise in different communities created through social interactions in the cultural context where they occur, such as computers, tablets, or smartphones. This facilitates insight into the relationship of adolescents with current advertising being generated, consumed, and shared in digital environments.

The advent of the internet has led to a different experience in the world of advertising and brands (Hine, 2008; Reyes-Reina, 2013), because adolescent interaction creates frameworks of action and meanings that emerge through these new social practices. This is precisely what brands aim to construct with their content (Castelló-Martínez & Del-Pino-Romero, 2018) and advertising communications (Waqas et al., 2021); the creation of a brand experience that generates meanings and confers symbolic value to the products they launch in the market (Eguizábal, 2007).

Considering all these aspects, our research involves creating a virtual community that allows us to establish patterns in the relationships of community members with the various creative outputs of advertising brands and the content they generate and distribute, mainly on social networks, to improve their market objectives. These interactions occur spontaneously among participants and are also suggested by researchers when proposing content for viewing, debate, and discussion.

The virtual community created for this purpose, called «Current Adolescents» follows the MUD (Multiple User Dialogue) type, allowing for online surveys, forums, focus groups, and even reward programs to encourage participation. However, in this case, it was not necessary, as participation was consistently satisfactory. It was designed, created, and managed under the auspices of the Chair of Digital Communication in Childhood and Adolescence, in collaboration with the ASOE Teaching Innovation Group, and specifically with the teaching innovation project of the University of Valladolid: Social Advertising and Service Learning, as well as with the participation of the guidance department and tutors from the secondary education center that collaborated in this research.

The community consisted of 95 minors from first to fourth year of secondary education. All participating students were aged between 12 and 16 years, without significant knowledge of the advertising world, and had obtained the corresponding parental and guardian permission to participate in the research.

For this research, four activities related to working on communication pieces generated by different commercial brands were proposed to the digital community. Community members were required to express their opinions in different formats: a forum, through a travel diary, and recorded in a blog. Finally, a survey was conducted from which the data reflected in the results and conclusions of this article were extracted.

The activities carried out were:

Activity 1. Shared Space and Time: Community members were encouraged to freely exchange anything of interest: news, memes, advertisements, campaigns, etc. They were invited to explain what they found most interesting and motivating and to give their opinion on all new advertising formats. In this activity, researchers moderated while introducing topics and news for the community to give their opinion and generate debates.

Activity 2. TikTok: Content and Brands: This activity was designed for adolescents already familiar with TikTok to critically view the content presented to them and respond to various questions:

– Is TikTok an effective space for brands? Why?

– What should brands consider when communicating on TikTok?

– How do they think brands can innovate on this social network?

Finally, community members were asked to find examples of effective advertising and as well as examples of advertising they considered to be poor in quality or harmful.

Activity 3. Branded Content: This activity provided explanation of this new marketing technique for generating brand-related content, intended to promote brand awareness rather than actually selling products or services. This involves creating content for entertainment, ranging from video games, street actions, to stories with a beginning, middle, and end. Once this concept was presented and understood through some examples, participants were asked to locate branded content from brands they follow that clearly connect with their interests and tastes.

Activity 4. New Advertising Formats: This activity aimed to propose new challenges. Participants were encouraged to use their creativity to imagine new advertising formats: media, styles, platforms, messages, etc., that are yet to be explored, conducting a reflective exercise by identifying the strengths and weaknesses of their proposals.

A brainstorming session was also conducted on the values and interests that connect with their lifestyle and whether they are represented in the different brands they follow and consume.

The second instrument used in the methodological approach is observation. This is scientific observation as the researchers are in direct contact with the observed phenomenon, in this case, the members of the virtual community, without intermediaries, and can record behavior concerning the object of study. It is also participatory observation (Aguiar, 2015), allowing interaction with the virtual community to resolve potential issues, stimulate debate and participation, focus discussion, and introduce audiovisual content to complement that freely provided by community members. Finally, it is direct, as it details the phenomenon being pursued.

To conclude the study, a survey consisting of 15 closed-ended questions was conducted, allowing for correlations between variables and the formulation of significant conclusions (López-Romo, 1998). The survey used was structured, and thus the questions were posed equally to all members of the virtual community. In preparing the survey, the research objectives, the specific characteristics of the virtual community members, and the appropriateness of the wording to their level of understanding and language were considered. A pilot test with 5 members was conducted to establish its validity.

The virtual community operated throughout the second trimester of the 2023-2024 academic year (from January to March), for 11 weeks. It is noteworthy that the months preceding the creation of the virtual community were dedicated to finding the center where the research would be conducted, explaining the research project, training the collaborating teachers, and obtaining permission for the minors' participation.

This research was carried out in different phases (Table 1), ranging from activity planning to drafting conclusions.

Table 1. Research Phases

|

Phase 1 |

Creation of the Virtual Community. |

|

Phase 2 |

Planning the 4 Scheduled Activities. |

|

Phase 3 |

Viewing Selected Content. |

|

Phase 4 |

Developing the Blog and Forum. |

|

Phase 5 |

Conducting the Survey. |

|

Phase 6 |

Data Collection and Analysis. |

|

Phase 7 |

Conclusions |

Source: Own elaboration.

5. Results and Discussion

For the analysis of the results, it is most noteworthy that the virtual community was operational, as previously mentioned, throughout the second trimester of the 2023-2024 academic year (from January to March), lasting 11 weeks. It was established as an open space for all participants to reflect on important aspects of the relationship between advertising communication and adolescents.

The researchers intervened throughout the project through participatory observation, encouraging participation, promoting and guiding debates, and proposing content for viewing and discussion.

The results of these analyses and the data obtained from the survey allow us to assert the following findings, divided into two sections: Elements that facilitate connection with adolescents and those that distort or hinder the connection:

5.1. Elements Facilitating Connection with Adolescents

The results of this work allow us to assert that adolescents are in a complex stage, seeking their own identity, characterized by the following aspects:

– They are predominantly technological, viewing technology as a transformative tool that offers new ways to communicate and relate. They are motivated to learn and explore these new forms.

They constitute the first group in constant contact with technology, interacting with it naturally. This relationship allows for the creation of advertising campaigns adapted to the contexts where adolescents are, such as social media networks, giving campaigns greater acceptance and credibility. This fact enables the cultivation of personalized experiences, a key element in sparking interest and acceptance of content by technological users who feel that brands address them personally rather than generally, unlike traditional media.

– Adolescents are very enthusiastic about these first personal experiences they encounter (Wolf, 2020), valuing them very positively and feeling connected to them, as they are outside the usual formats. They also feel like protagonists of this advertising communication coming through social networks.

– It is noteworthy that adolescents are very attracted to content related to friendship, romantic relationships, and interactions with parents and other adults, in other words, everything related to human interactions. These topics constitute their main area of interest, where adolescents must navigate properly in order to acquire emotional maturity.

– Creativity has always been a fundamental mechanism used in advertising to connect with audiences. However, because adolescents are digital natives who have grown up consuming and generating content, they are very open to creative experimentation. Therefore, brands must make their messages more original and differentiated in order to connect with their audience and avoid being repetitive, which would likely lead to immediate rejection.

5.2. Elements that Hinder Connection with Adolescents

When analyzing factors that impede the connection of advertising messages with today’s adolescents, we primarily encounter three challenges: stereotypes, identity construction information, and advertising methods employed to relate to adolescents.

– Stereotypes: Stereotypes have always been employed in advertising communication. In fact, they are the basis of mass communication. However, adolescents tend to reject them because they prefer to oppose established norms. In this way, today’s stereotypical adolescent differs significantly from that of previous generations.

Today’s adolescents are more independent, better educated, and freer because they begin to master the channels where discourses are generated earlier. They are both content creators and consumers. They are becoming aware of social issues and feel co-responsible for behaviors such as environmental conservation, nonhuman animal care, and immigration, among other significant social causes.

It is important to note that, as a group with a wide age range, clear differences are observed between younger members aged 12 to 14 and those a bit older, up to 16 years old.

In the first group, corresponding to the first cycle of secondary education, technology use occupies 31 % of their leisure time, while in the second group, this figure rises significantly to 45 %, making it the preferred leisure activity for adolescents, relegating other activities like physical playing, listening to music, reading, and talking with family to the background (data obtained from the survey conducted).

It is also noteworthy that within the preferences for interactive leisure, technology use is equally preferred to be enjoyed with friends, indicating that interactive leisure at this age has a significant social component.

Regarding advertising, adolescents need to experience advertising communication, both social and commercial, that considers and respects them as a target audience capable of using services, acquiring consumer products, and showing favorable or unfavorable attitudes towards brands and their messages.

– Importance in Identity Construction: Currently, adolescents frequently interact with social networks, the internet, and other media through smartphones (Pérez-Escoda, 2018). This exposure to a vast amount of information positively impacts their identity construction but also presents challenges.

Media must reflect on how adolescents are portrayed. The first challenge is finding a communication style that appeals to them while also focusing on appropriate content.

Research often highlights violence and sex (Colas-Bravo & Quintero-Rodríguez, 2020; De-Jesús-Sánchez, 2020), which, when presented inappropriately, negatively influence adolescents by endorsing aggressive behaviors and unsatisfactory sexual relationships, along with related harmful issues such as sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancies.

Other perjudicial content includes drugs, tobacco, alcohol, and glorifying eating disorders. Aware of these difficulties, brands must strive to establish a positive relationship by understanding adolescents' needs, respecting them, and offering products with positive values to gain their acceptance.

– Advertising Methods to Relate to Adolescents: Adolescents are a continuously developing group (Duffy, 2022) to whom idealization, fantasies, and promises of improvement are significantly appealing.

Their perception of reality is distorted, and they seek or want to create their own reality.

Advertising and brands, if they wish to connect with adolescents, must present ideas that, although distant from existing reality, are valid for creating their own reality and experimenting with these methods. This is often done through influencers who are highly attractive to them, necessitating regulation (Ramos-Gutiérrez & Fernández-Blanco, 2021). This is not an easy task, as it can easily fall into exaggerated and unbelievable communication, leading to immediate rejection.

Ultimately, adolescents expect brands to understand and listen to them, establishing a more personal relationship rather than solely focusing on product consumption.

These results demonstrate that the digital community members' competence in understanding advertising content presented in various activities is high. In this regard, we align with studies by Scolari (2018) on transmedia competencies and the need to improve advertising literacy among adolescents, as referenced by Cuervo-Sánchez & Medrano-Samaniego (2013) and Muñoz-Guevara et al., (2021). This need is ongoing, as the advertising industry constantly develops new strategies to capture adolescents' attention and persuade them toward consumption, often including highly effective endorsers (Harrigan et al., 2021) to connect with them (Castelló-Martínez et al., 2016), and experimenting with media, channels, and formats (Núñez-Gómez et al., 2020).

Despite the results indicating adolescents' natural competence in navigating the media landscape (Bassiouni & Hackley, 2014), networks (Echegaray-Eizaguirre, 2015), and understanding commercial content, their need for special protection (Del-Moral-Pérez, 1998) as individuals in the personality development stage (Páramo, 2008; Rodríguez-Clavel, 2022) requires a constant commitment from various institutions to ensure the proper education (García-Aretio, 2019) of generations that understand the nature of advertising activities in their different formats (García et al., 2018) and develop competencies to critically evaluate the creative commercial messages designed and produced for them.

6. Conclusions

Throughout this study, we have observed that adolescents as screen consumers involve interest from multiple aspects from distinct perspectives. Advertising communication thus faces a significant challenge, as traditional methods are no longer effective and need to create new communicative formats to connect with adolescents, allowing brands to convey the values and aspirations adolescents intensely seek.

If advertising messages do not offer engaging experiences, adolescents will automatically reject them. However, if advertisers can establish dialogues with their adolescent publics and provide them ways of interacting, empathizing, and enjoying advertising communication, these communicative discourses will have high commercial value.

In conclusion, we can affirm that for advertising to be effective, it must connect with this particular audience. To do so, it must understand adolescent media behaviors, their ways of understanding life, the models that represent them, and the stereotypes they reject.

In this complex and constantly changing media landscape, advertising will not disappear, just as it did not fade during other technological transformations. However, to maintain significant levels of effectiveness, it must adapt its content, messages, and formats to new realities, thus requiring creativity more than ever. Advertising has consistently demonstrated an enormous capacity for adaptation throughout history; it is a communicative form capable of reinventing itself to continue fulfilling its commercial functions. Wherever there is a significant audience, there will be advertising. The current challenge is to understand where adolescents are and how they want to be communicated with.

Ethics and Transparency

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Maverick for his services in translating the article.

Funding

This research has been carried out within the framework of the Teaching Innovation, Social Action and Educational Opportunities Group (ASOE), recognized by the University of Valladolid, which includes the Project for Teaching Innovation, Social Advertising and Service Learning. An interesting relationship to promote the development of attitudes, values and social norms in university and primary school students.

Author Contributions

|

Function |

Author 1 |

Author 2 |

Author 3 |

Author 4 |

|

Conceptualization |

|

X |

|

|

|

Data curation |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Formal analysis |

X |

|

X |

|

|

Financing Acquisition |

|

|

|

|

|

Investigation |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Methodology |

|

X |

|

|

|

Project administration |

X |

|

|

|

|

Resources |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Software |

X |

|

|

|

|

Supervision |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Validation |

|

|

X |

|

|

Display |

X |

|

|

|

|

Writing – Original draft |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Writing – Review and editing |

X |

X |

X |

|

Bibliographic references

Aguiar, E. P. (2015). Observación participante: Una introducción. Revista San Gregorio, 80-89. https://doi.org/10.36097/rsan.v0i0.116

Arbaiza., F., Robledo-Dioses., K. & Lamarca., G. (2024). Alfabetización publicitaria: 30 años en estudios científicos [Advertising Literacy: 30 Years in Scientific Studies]. Comunicar, 32(78), 166-178. https://doi.org/10.58262/V32I78.14

Alcoceba-Hernando, J. A., & Cadilla-Baz, M. (2006). Los Servicios de información juvenil en España. Injuve.

Bassiouni, D. H. & Hackley, C. (2014). «Generation Z» children’s adaptation to digital consumer culture: A critical literature review. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 13(2), 113-133. https://doi.org/10.1362/147539214X14024779483591

Bauman, Z. (2007). Entre nosotros, las generaciones. En J. Larrosa (Ed.), Entre nosotros: Sobre la convivencia entre generaciones (pp. 101-127). Obra Social Caixa Catalunya.

Bawden, D. (2002). Revisión de los conceptos de alfabetización informacional y alfabetización digital (M. P. F. Toledo & J. A. G. Hernández, Trads.). Anales de documentación: revista de biblioteconomía y documentación, 5, 361-408.

Beck, U. (2008). Generaciones globales en la sociedad del riesgo mundial. Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacional, 82-83, 19-34.

Bringué-Sala, X. & Sádaba-Chalezquer, C. (2009). La generación interactiva en España: Niños y adolescentes ante las pantallas. Ariel.

Cárdenas-García, I. & Cáceres-Mesa, M. L. (2019). Las generaciones digitales y las aplicaciones móviles como refuerzo educativo. Revista Metropolitana de Ciencias Aplicadas, 2(1), 25-31.

Castelló-Martínez, A. & Del-Pino-Romero, C. (2018). Los contenidos de marca: Una propuesta taxonómica. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 47, 125-142. https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2018.0.125-142

Castelló-Martínez, A., Del-Pino-Romero, C. & Tur-Viñes, V. (2016). Estrategias de contenido con famosos en marcas dirigidas a público adolescente. Revista ICONO14 Revista científica de Comunicación y Tecnologías emergentes, 14(1), 123-154. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v14i1.883

Cataldi, Z. & Dominighini, C. (2015). La generación millennial y la educación superior. Los retos de un nuevo paradigma. Revista de informática educativa y medios audiovisuales, 12(19), 14-21.

Colás-Bravo, P. & Quintero-Rodríguez, I. (2020). Respuesta de los/as adolescentes hacia una campaña de realidad virtual sobre violencia de género. Revista Prisma Social, 30.

Cuervo-Sánchez, S. L., & Medrano-Samaniego, C. (2014). Alfabetizar en los medios de comunicación: Más allá del desarrollo de competencias. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 25(2), 111-131. https://doi.org/10.14201/11577

De-Jesús-Sánchez, M. (2020). La violencia digital en la Generación Z. Revista mexicana de orientación educativa, Edición Especial No 5, 2-9.

Del-Moral-Pérez, M. E. (1998). Protección jurídica de la infancia ante los medios de comunicación. Comunicar, 5(10), 198-206. https://doi.org/10.3916/C10-1998-30

Duffy, B. (2022). El mito de las generaciones. Urano.

Echegaray-Eizaguirre, L. (2015). Los nuevos roles del usuario: Audiencia en el entorno comunicacional de las redes sociales. En N. Quintas-Froufe & A. González-Neira, La participación de la audiencia en la televisión: De la audiencia activa a la social (pp. 27-46). Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación (AIMC).

Eguizábal-Maza, R. (2007). De la publicidad como actividad de producción simbólica. En M. I. Martín-Requero & M. C. Alvarado-López, Nuevas tendencias en la publicidad del siglo XXI (pp. 13-34). Comunicación Social.

Espiritusanto-Nicolás, O. (2016). Generación Z: Móviles, redes y contenido generado por el usuario. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 114, 111-126. https://tinyurl.com/yyywvpej

Fernández-Gómez, E., Segarra-Saavedra, J. & Feijoo, B. (2023). Alfabetización publicitaria y menores. Revisión bibliográfica a partir de la Web of Science (WOS) y Scopus (2010-2022). Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 81, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.4185/rlcs.2023.1892

García-Aretio, L. (2019). Necesidad de una educación digital en un mundo digital. RIED. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 22(2), 9. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.22.2.23911

García-García, F., Tur-Viñes, V., Arroyo-Almaraz, I. & Rodrigo-Martín, L. (2018). Creatividad en publicidad: Del impacto al comparto. Dykinson.

Garitaonandia, C. & Garmendia, M. (2007). Cómo usan internet los jóvenes: hábitos, riesgos y control paternal. LSE. EU Kids Online.

George-Reyes, C. E. (2020). Alfabetización y alfabetización digital. Transdigital, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.56162/transdigital15

Harrigan, P., Daly, T. M., Coussement, K., Lee, J. A., Soutar, G. N. & Evers, U. (2021). Identifying influencers on social media. International Journal of Information Management, 56, 102246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102246

Hine, C. (2008). Virtual Ethnography: Modes, Varieties, Affordances. En N. Fielding, R. Lee, & G. Blank, The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods (pp. 257-270). SAGE Publications, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857020055.n14

Hudders, L., De Jans, S. & De Veirman, M. (2021). The commercialization of social media stars: A literature review and conceptual framework on the strategic use of social media influencers. International Journal of Advertising, 40(3), 327-375. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1836925

Hudders, L. & Lou, C. (2022). The rosy world of influencer marketing? Its bright and dark sides, and future research recommendations. International Journal of Advertising, 42(1), 151-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2022.2137318

Injuve. (2007). Sondeo de opinión y situación de la gente joven (2a encuesta de 2007) Uso de TIC, ocio y tiempo libre, información. Injuve. https://tinyurl.com/ypjnx2vw

Jones, S., & Fox, S. (28th january 2009). Generations Online in 2009. Pew Research Center. https://tinyurl.com/3s93ptpt

Lara, I. & Ortega-Cachón, I. (2016). Los consumidores de la Generación Z impulsan la transformación digital de las empresas. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 114, 71-82. https://tinyurl.com/2p9kzahe

Lenhart, A. (2005). Protecting Teens Online. Pew Research Center. https://tinyurl.com/4zcvwt8k

Lenhart, A., & Madden, M. (2007). Social Networking Websites and Teens. Pew Research Center. https://tinyurl.com/2jcd75pp

Livingstone, S. (2003). Children´s use of the Internet: reflections on the emerging research Agenda. New Media y Society 5(2), 125-147. https://tinyurl.com/y5hnyh9e

Livingstone, S., & Haddon, L. (2009). EU Kids Online. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology, 217(4), 236-239. https://tinyurl.com/5n9548mp

López-Romo, H. (1998). La metodología de la encuesta. En J. Galindo-Cáceres, Técnicas de investigación en sociedad, cultura y comunicación, (pp. 33-74). Addison Wesley Longman.

Macgill, A. (24th october 2007). Parent and Teen Internet Use. Pew Research Center. https://tinyurl.com/2jrftktf

Muñoz-Guevara, E., Velázquez-García, G. & Barragán-López, J. F. (2021). Análisis sobre la evolución tecnológica hacia la Educación 4.0 y la virtualización de la Educación Superior. Transdigital, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.56162/transdigital86

Núñez-Gómez, P., Falcón, L., Figuerola, H. & Canyameres, M. (2015). Alfabetización publicitaria: El recuerdo de la marca en los niños. En A. Álvarez-Ruiz y P. Núñez-Gómez, Claves de la comunicación para niños y adolescentes: Experiencias y reflexiones para una comunicación constructiva (pp. 111-131). Fragua. https://tinyurl.com/cdzrcrvz

Núñez-Gómez, P., Rodrigo-Martín, L., Rodrigo-Martín, I. & Mañas-Viniegra, L. (2020). Tendencias de Consumo y nuevos canales para el marketing en menores y adolescentes. La generación Alpha en España y su consumo tecnológico. Revista Ibérica de Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informação; Lousada, 34, 391-407. https://tinyurl.com/2s4cnh54

Páramo, P. (2008). La construcción psicosocial de la identidad y del self. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 40(30), 539-550.

Pérez Escoda, A. (2018). Uso de smartphones y redes sociales en alumnos/as de Educación Primaria. Revista Prisma Social, (20), 76-91, https://tinyurl.com/2m7yptzw

Pierre-Murray, K. (2012). Niñez, adolescencia, publicidad y alfabetización mediática. Revista Reflexiones, Número Especial Jornadas de Investigación Interdisciplinaria, 125-131. https://doi.org/10.15517/rr.v0i0.1528

Pink, S., Horst, H., Postill, J., Hjorth, L., Lewis, T. & Tacchi, J. (2019). Etnografía digital. Principios y práctica (R. Filella, Trad.). Ediciones Morata.

Ramos-Gutiérrez, M. & Fernández-Blanco, E. (2021). La regulación de la publicidad encubierta en el marketing de influencers para la Generación Z: ¿Cumplirán los/as influencers el nuevo código de conducta de Autocontrol? Revista Prisma Social, 34.

Reyes-Reina, D. (2013). La etnografía en los estudios de marca: Una revisión bibliográfica. Pensamiento y Gestión, 34, 211-234.

Rodrigo-Martín, L., Rodrigo-Martín, I. & Muñoz-Sastre, D. (2021). Los Influencers Virtuales como herramienta publicitaria en la promoción de marcas y productos. Estudio de la actividad comercial de Lil Miquela. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 79. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2021-1521

Rodríguez-Clavel, M. (2022). Identidad y adolescencia: La educación artística, visual y audiovisual frente a la influencia de redes sociales y publicidad. Communiars. Revista de Imagen, Artes y Educación Crítica y Social, 8. https://tinyurl.com/ttmpzznh

Saavedra-Llamas, M., Papí-Gálvez, N. & Perlado-Lamo-de-Espinosa, M. (2020). Televisión y redes sociales: Las audiencias sociales en la estrategia publicitaria. Profesional de la información, 29(2). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.mar.06

Sádaba, C. & Feijoo, B. (2022). Atraer a los menores con entretenimiento: Nuevas formas de comunicación de marca en el móvil. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 13(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM.20568

Scolari, C. A. (2018). Adolescentes, medios de comunicación y culturas colaborativas. Aprovechando las competencias transmedia de los jóvenes en el aula. EC | H2020 | Research and Innovation Actions. https://tinyurl.com/pyhvz2t9

Souto-Kustrín, S. (2007). Juventud, teoría e historia: La formación de un sujeto social y de un objeto de análisis. https://tinyurl.com/52vbmrcf

Tafesse, W. & Wood, B. P. (2021). Followers’ engagement with Instagram influencers: The role of influencers’ content and engagement strategy. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102303

Valor, J. & Sierber, S. (coord.) (2004). Uso adictivo de los jóvenes hacia internet y la telefonía móvil. E-business center, PwC y IESE.

Van-den-Abeele, E., Vanwesenbeeck, I., & Hudders, L. (2023). Child’s privacy versus mother’s fame: unravelling the biased decision-making process of momfluencers to portray their children online. Information, Communication & Society, 27(2), 297–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2023.2205484

Van-Reijmersdal, E. A., Rozendaal, E., Hudders, L., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Cauberghe, V. & Van-Berlo, Z. M. C. (2020). Effects of Disclosing Influencer Marketing in Videos: An Eye Tracking Study among Children in Early Adolescence. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 49(1), 94-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2019.09.001

Waqas, M., Hamzah, Z. L. & Mohd-Salleh, N. A. (2021). Customer experience with the branded content: A social media perspective. Online Information Review, 45(5), 964-982. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-10-2019-0333

Wolf, A. (2020). Gen Z & Social Media Influencers: The Generation Wanting a Real Experience. Honors Senior Capstone Projects, 51. https://tinyurl.com/dewz5yp9

Zozaya-Durazo, L. D., Feijoo-Fernández, B. & Sádaba-Chalezquer, C. (2022). Análisis de la capacidad de menores en España para reconocer los contenidos comerciales publicados por influencers. Revista de Comunicación, 21(2), 307-319. https://doi.org/10.26441/RC21.2-2022-A15