index●comunicación

Revista científica de comunicación aplicada

nº 15(1) 2025 | Pages 77-97

e-ISSN: 2174-1859 | ISSN: 2444-3239

Advertising and Children: the Viewpoint of Mothers

Publicidad y menores: qué piensan las madres

Received on 10/09/2024 | Accepted on 19/11/2024 | Published on 15/01/2025

https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/15/01Ymenor

Mayte Donstrup | Universidad Rey Juan Carlos

mariateresa.donstrup@urjc.es | https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6236-4967

Noelia García-Estévez | Universidad de Sevilla

noeliagarcia@us.es | https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7871-2345

Abstract: This article explores the role of mothers in the literacy of media advertising by focusing on their perception of advertising aimed at children of preschool age in Spain. It analyses how they evaluate advertising discourse, especially branded content, and the features they consider important in advertising aimed at their children. This research is based on focus group discussions with mothers, which show that they engage in the critical assessment of advertising messages by playing the role of "gatekeepers" in commenting on the adverts and explaining them to their children. The mothers advocate for stricter regulations, especially in the food industry. Although they can recognise branded content, they initially did not associate it with advertising due to its playful and narrative format. However, they conclude that this type of content can be useful if it is clearly labeled as advertising and promotes educational values and healthy lifestyles.

Keywords: Media Literacy; Children's Advertising; Branded Content; Mothers.

Resumen: Este artículo explora el papel de las madres en la alfabetización mediática publicitaria, enfocándose en su percepción de la publicidad dirigida a niños en edad preescolar en España. Se analiza cómo evalúan el discurso publicitario, especialmente el branded content, y qué elementos consideran importantes en los anuncios para sus hijos. La investigación se basa en grupos de discusión con madres, revelando que estas realizan una lectura crítica de los mensajes publicitarios y ejercen un rol de "gatekeeper", comentando y explicando los anuncios a sus hijos. Las madres abogan por una regulación más estricta, especialmente en la industria alimentaria. Aunque reconocen el branded content, inicialmente no lo asocian con la publicidad debido a su formato lúdico y narrativo. Sin embargo, concluyen que este tipo de contenido puede ser efectivo si se etiqueta claramente como publicidad y si promueve valores educativos y estilos de vida saludables.

Palabras clave: alfabetización mediática; publicidad infantil; branded content; madres.

To quote this work: Donstrup, M. & García-Estévez, N. (2025). Advertising and Children: The Viewpoint of Mothers. index.comunicación, 15(1), 77-97. https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/15/01Ymenor

1. Introduction

Advertising in its various formats is omnipresent in our daily lives as citizens.

As such, it can be inferred that citizens need sufficient critical thinking skills in order to grasp the messages and their intent; in other words, people must have media literacy skills. This study defines media literacy as the ability to decifer, evaluate, and analyse media content in a variety of formats (Aufderheide, 1993). In particular, this paper focuses on understanding the unique features of advertising literacy, or in other words, literacy related to the persuasive discourse communicated through the media.

More specifically, we will analyse the mother’s role in monitoring children's advertising, and especially branded content, by looking at what they think , how they evaluate advertising discourse, and the features they believe should be included in advertising aimed at children.

Branded content refers to the creation of relevant and engaging content associated with a brand, which is aimed at consumers, the goal of which is to build an audience and make an emotional connection with them (García-Estévez & Cartes-Barroso, 2022). This type of content includes video, audio, story-telling, and games (Muntinga et al., 2011), which is presented in a non-intrusive way, implicitly conveying the values of the brand.

Interaction with this type of content improves attitudes toward the brand (Schivinski et al., 2016), fosters loyalty (Helme-Guizon & Magnoni, 2019), and can increase purchase intent (Carlson et al., 2019). This approach becomes especially relevant with children, where brands try not only to capture their attention, but also to build trust and loyalty with their parents through content perceived as entertaining and useful.

2. Advertising Literacy

The media landscape is constantly evolving, and advertisers are adapting their formats to an ever-changing environment (De-Pauw et al., 2018). For example, contemporary advertising combines traditional formats with the integration of adverts into other types of content, whether it is fiction, information, influencer marketing, or interaction with the brand (Daems et al., 2017; Hudders et al., 2017; De-Pauw et al., 2018). In this ever-changing context, there is a need to understand how audiences engage with different types of advertising formats, and a need for media literacy as well.

According to Malmelin (2016), media literacy refers to the ability to read and critically analyse different types and means of media depiction. This author offers the following description:

From a theoretical perspective, literacy is an umbrella term that comprises different types of reading and interpretation. In practice, literacy is the individual’s personal ability to understand different kinds of signs and symbolic systems and, on the other hand, the ability to produce different kinds of messages by using these symbolic systems (2016: 131).

Advertising literacy is based on these assumptions. Moreover, it posits the idea that in order to interpret the symbolic systems of the media society, individuals must possess at least some literacy skills related to the specific symbolic system in question (Fernández-Gómez et al., 2023). In this regard, advertising has unique communicative features that require specific reading and writing skills, which are different from those required for understanding other symbolic forms of communication (Malmelin, 2016). Thus, advertising literacy can be defined as the beliefs shaped by consumers related to the motives, strategies, and tactics used in advertising (Rozendaal et al., 2013). Similarly, according to Pérez-Sánchez et al., advertising literacy is defined as «the collection of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values necessary for understanding and critically analysing the advertising information we receive, and for making informed decisions about the consumption of goods and services» (2021: 305). In similar terms, Livingstone and Helsper define advertising literacy as «the ability to critically analyze and evaluate advertising, including an understanding of advertising messages, the techniques used, and the goals of advertising» (2006: 145). Regarding the demands that adverts place on the audience for the purpose of being understood, Scott argues that advertising text implies that the reader must have the following skills:

The reader must be selective, active and sceptical during the reading experience […] able to make subtle inferential distinctions using a variety of verbal and non-verbal cues, simultaneously an agile reader, who can change frames and strategies even within the temporal space of a single reading, and alter expectations, as the textual task seems to suggest an experienced reader, one with a broad-based interpretive repertoire, including a capacity for highly metaphorical, imaginative thinking (1994: 475).

2.1. Advertising Literacy and Children

If advertising literacy requires the critical ability to recognise the symbolic capital of the advertising ecosystem, whether media, social, or economic, (Scott, 1994; Fernández-Gómez et al., 2023), and if we consider this ability in children, we find that the latter are in the midst of a process of cognitive and social development.

De-Jans et al., (2017) reviewed ten years of research (2006-2016) on advertising targeted at children, and identified five areas of study: (1) the effects of advertising; (2) the processing of advertising; (3) the content and features of advertising; (4) social influences; and (5) the protection and empowerment of children. As for the processing of advertisements, an area where research related to advertising literacy takes place, various studies highlight the lack of attention from academia to new formats (De-Jans et al., 2017; Fernández-Gómez et al., 2023), which creates a gap in the academic literature on how to help children activate their advertising literacy in the face of embedded formats. The limited number of studies investigating non-traditional advertising literacy in children focus on formats that combine information and entertainment, such as product placement (De-Jans et al., 2017), brand placement (De-Pauw et al., 2018), advergames (Mallinckrodt & Mizerski, 2007; Hudders et al., 2017; De-Jans, et al., 2024), as well as banners (De-Jans et al., 2020), interactive ads on social media (De-Pauw et al., 2018; Taken-Smith, 2019; Feijoo & Sádaba, 2022; Taken-Smith, 2022), and influencer marketing (van-Dam & van-Reijmersdal, 2024). Regarding the latter, it is worth highlighting the findings of van-Dam & van-Reijmersdal (2024), who observed that adolescents showed greater affinity and compassion toward advertising content disseminated by influencers, rather than critically analyzing the messages.

In terms of age range, a systematic study by Fernández-Gómez et al., (2023) points out the need to expand the knowledge of media advertising literacy in preschool-aged children. As for the preschool stage, other variables come into play, such as the role of parents and educators. As noted by the AdLit project (Hudders et al., 2017), the information provided by parents can be used to develop educational programs and awareness campaigns. Regarding empirical studies that explore the role of parents in childrens’ advertising literacy, some that stand out include the work of Oates et al., (2014) and Dens et al. (2007), who focus on television advertising in the food industry. Both studies identify the role of parents as gatekeepers and point to the multidimensional construct that operates at the moment of consuming advertising messages. This includes activating awareness of the commercial intent behind the message, the potential conflict it may generate, and an independent component related to the advertised food items.

Based on the theoretical framework, the main objective of this study is to analyse the role of mothers in the advertising literacy of preschool children in Spain, as well as their involvement in how their children consume advertising content, especially branded content. Thus, by considering advertising formats and the focus of the study, which is mothers of preschool children, this paper has taken an exploratory approach. The specific objectives are as follows:

1. Determine the level of knowledge and understanding that Spanish mothers have of advertising strategies aimed at preschool children.

2. Evaluate the influence mothers have on how children interpret and respond to advertising messages.

3. Identify the mothers' perceptions and attitudes toward the use of branded content with preschool children as a communication tool.

4. Methodology

To achieve the proposed objectives, the authors have used one of the quintessential techniques for media literacy studies, which is the focus group. A focus or discussion group is a qualitative data collection method that seeks to understand how a group of people interpret a phenomenon through group discussion. The participants are brought together by the researcher, who sometimes acts as the discussion moderator as well. Morgan explains the concept as follows: «Focus groups are group interviews. A moderator guides the interview while a small group discusses the topics that the interviewer raises. What the participants in the group say during their discussions are the essential data in focus groups» (1997: 1). The key aspect of this technique is the interaction and debate among the participants: «In a lively group conversation, the participants will do the work of exploration and discovery for you. Similarly, they will not only investigate issues of context and depth but will also generate their own interpretations of the topics» (1997: 12). In this way, focus group data is produced by interaction between the participants of the group. Individuals present their own viewpoints and experiences, but they also listen to others, reflect on what is being said and, as a result of the discussion, sometimes reconsider their own perspective (Finch & Lewis, 2013).

If we consider the specific aspects of media advertising literacy, the discussion was designed according to the guidelines of Rozendaal et al., (2011). The model proposed by the authors differentiates between two domains of advertising literacy. The first is conceptual advertising literacy, which refers to the ability to recognize a commercial message and understand its intention. Specifically, this domain includes the following aspects:

1. Recognizing advertising and being able to distinguish it from other media content such as information and entertainment.

2. Understanding the commercial intent, or knowing that advertising aims to sell products.

3. Recognising the source of advertising, or who pays to insert the ads.

4. Identifying the target audience, which means understanding the concept of targeting and audience segmentation.

5. Identifying persuasive intent, or the fact that advertising tries to influence consumer behavior, for instance, by changing people’s attitude toward a product.

6. Persuasive tactics, or understanding that advertisers use specific strategies to convince.

7. Detecting advertising bias, or being aware of the discrepancies between the advertised product and the real product.

The second dimension is attitudinal advertising literacy, which is evaluative in nature. This dimension has two components: scepticism toward advertising, or the tendency to distrust advertising, and the level of either liking or disliking the advert.

4.1. Research design

Based on the foregoing, three blocks of questions have been compiled with the aim of understanding the following: participants’ perception of advertising, especially branded content; their ability to identify its objectives; and the parents’ evaluation of the advertising discourse, the latter of which is a key aspect of the research. To this end, four discussion modules were developed: introduction (to break the ice among participants); transition (with initial queries about advertising); key module (with questions aimed at reaching the proposed objectives of the study); and a final module (where some activities were developed in order to apply and put into practice the key questions) (Krueger, 1997). In summary, the questions used in the focus groups were as follows:

1º Introduction

– The moderator presents the study.

– The participants introduce themselves: Could you please tell everyone your name and what type of work you do? How old are your children? Do they go to school or daycare?

– Do you usually watch TV or other entertainment media? When do you do so? Do you watch it with your children?

2º Transition

– On television there is a wide variety of formats, one of which is advertising: Could you tell me what you think advertising is?

Based on the participants' responses, follow-up questions were sometimes asked, such as the following: What are the objectives of advertising? How do you recognise it? Is it easily distinguishable from other content?

– Do you believe advertising is effective?

– Do you remember an advertisement that has stuck in your mind? Could you tell us why it was memorable? Do you recall any adverts from your childhood?

– We've discussed your childhood memories of advertisements. Now that you are mothers, what do you think of advertising aimed at children? Do you think they should have any specific features, given its audience? Do your children see advertising?

The moderator now makes a summary to gather essential aspects of the section and obtain the participants' opinions about the glossary.

3º Key questions

– Have you ever heard the term “branded content”? What do you think this concept means?

– Do you think branded content is different from traditional advertising? [If there is no response: “Well, the term means…”] In what ways do you believe it is different?

– Do you think branded content has a different purpose or advantage compared to conventional advertising?

– How do you assess the value of using branded content in communications aimed at children and families?

– Do you think branded content might confuse or influence children differently compared to more overt advertising?

– How do you think branded content should adapt or take into account the characteristics of the child audience?

– Do you think branded content should be subject to regulation or special recommendations when directed at children?

Activities

In this section, several creative activities were carried out in order to understand how mothers would approach their children if they were advertisers. In each discussion group, various advertising pieces were shown as follows:

– Exhibition of branded content aimed at children:

1. Barbie (https://www.youtube.com/@BarbieenCastellano/playlists)

2. Frosters by Llaollao (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=45p_b49eZBQ&t=10s).

Questions asked after viewing:

- Could you explain what you have just watched? Reformulation: If you had to explain the clip to a friend, how would you do it? Which characters appear? What story is being told?

- In the clip you watched, did anything stand out? If no ideas emerge from the group, ask if they consider it entertainment.

- [They should be given paper on which to write notes and later present their ideas. The paper will be collected afterward.] If you were creating adverts and had to develop an ad for:

a) A toy, for example, an action figure like Spiderman or Frozen.

b) Or a food product like Fantasmikos ice cream or TostaRica cookies, how would you do it?

4.2. Study corpus

The research sample consists of two focus groups, each comprising five women who are mothers of at least one preschool-aged child. This approach was deliberately chosen to ensure that the participants had hands-on and meaningful experience with advertising aimed at children, as well as branded content. In the end, the sample included ten people divided into two groups. According to Kitzinger & Barbour (1998), this type of qualitative research does not aim for a higher number of responses; instead, it focuses on meaningful answers. With this in mind, we used small focus groups to create a comfortable environment for the participants to share their opinions (Krueger, 1997). Furthermore, we followed the guidelines of other research into media literacy that have used two focus groups with significant results in the field of communication (Jones et al., 2010; Daems et al., 2017; Powell & Gross, 2018). In fact, as seen in the results, the second focus group led to informational saturation in terms of the opinions and topics that were emphasised by the participants.

As for the participants, they were selected through an open invitation on social media and local community groups, which helped reach a diverse audience. A description of the research subjects is summarised as follows:

1. Total number of participants: 10 women.

2. Age: The participants were between 35 and 50 years old, giving them a mature perspective on advertising and parenting. As for their children, the ages ranged from three to five years old, with one child being a nine-month-old baby.

3. Family status: All the participants are mothers, which is crucial for the focus of the study, as it aims to understand how mothers perceive advertising and how it is received by their children.

4. Education: The sample includes women with different educational backgrounds, ranging from secondary education to a university degree, which provided a diverse range of opinions and experiences concerning advertising.

5. Media experience: The participants were asked about their media consumption, and most reported watching television and using digital entertainment platforms both individually and with their children. The results section will delve into the specifics of their media viewing habits.

The focus groups were held on two dates in July 2024: The 12th and the 21st, with each lasting approximately 1 hour and 23 minutes. The setting for the discussions was a cosy and comfortable room with a table in the centre, which enabled interaction between the participants. To encourage participation among the women, the environment was organized as follows:

– Child supervision: The participants' children played in a nearby courtyard and were supervised by two caregivers. This enabled the mothers to feel comfortable and secure while taking part in the discussions, knowing that their children were well cared for.

– Relaxed atmosphere: An effort was made to create a stress-free environment where the women could freely express themselves. The conditions of the space, along with the group dynamics, were designed to foster open and honest dialogue.

The recordings were later transcribed manually, resulting in a total of 80 pages. Following the recommendations of Krueger (1998), the coding process was facilitated through the creation of a codebook, which highlighted the following key patterns to consider: frequency (repetition of participant answers); similarities (when the participants' comments were similar); correlation (when responses showed a pattern, such as dislike; and differences (the responses were markedly diverse).

To present the results in a consistent manner in line with the research objectives, we will first examine the consumption habits and data referring to how the mothers define advertising. Next, we will look at the mothers’ perception of the influence that advertising discourse has on their children, especially branded content. Lastly, we will address the creative segment and consider the opinion of mothers regarding the way advertising should be structured when directed at children.

In terms of consumption habits, it is worth noting that traditional television viewing has largely been replaced by streaming platforms, with only a few participants still following TV news or infotainment programs. However, regardless of the format, there is a consensus among participants that the time they spend watching TV is decreasing, as this time is now reserved mainly to enjoy the company of their children. One participant shared the following: «I watch less and less TV. I mean, when I come home, I don't turn it on. If someone turns it on, it's either [my husband] or our girl» (Participant 2, Group 2). In fact, this decline in TV viewing is partly due to advertising itself, as participants become annoyed by the large number of adverts: «Also, I think it’s terrible that there are more and more ads. When you try to watch a movie on TV, you can’t do it. It's impossible, because after the adverts you forget what you were watching» (Participant 3, Group 2). Thus, ad saturation becomes an obstacle for the reception of advertising, which is an aspect the participants do not recall during their own childhood:

Today, we are bombarded with advertising, because it’s not just on television. It’s everywhere, on many platforms, and I think the fast pace of life today plays a role. As I recall, I was always fascinated by advertising, so my opinion may not be very objective. But I remember when I was a child, my siblings and I used to play a game with the commercials (Participant 2, Group 1).

Regarding the aforementioned routine of children watching TV alone, the participants expressed concern about advertising's influence as they described the conversation topics that often arise in their homes because of the adverts. For instance, Participant 3 from Group 2 commented that her son often asks for toys he sees in commercials, while Participant 1 from the same group mentioned that her daughter struggles to fully understand the message behind the adverts, especially when gifts are offered in exchange for a subscription. As for television, both groups noted the ability of the new media channels to personalise content, which raised privacy concerns, as they find the large number of personalised ads disturbing: «It's quite scary. My daughter likes trampolines, so now if I look for information about them [on Instagram], I suddenly get all kinds of adverts about trampolines» (Participant 4, Group 1). Consequently, there is a consensus among participants that advertising is generally seen as negative: «Advertising has always had the tendency to deceive people in everyday life» (Participant 3, Group 2).

Next, regarding the definition of advertising offered by the participants, they highlighted its objectives and target audience, and they generally gave it a negative assessment with regard to its intention and narrative. The general opinion of the two groups is that advertising is primarily driven by commercial objectives, which often distort the true nature of the product. Adverts do this by emphasizing the positive features and concealing or downplaying the negative aspects and, in many cases, advertisers can even be deceptive regarding what they promote. Moreover, the opinion of Participant 3, Group 1 bears mentioning, as this participant emphasized the need for ads to be both entertaining and persuasive: «Advertising must entertain. It's not just about selling you a product; it also has to persuade you at the same time». Along the same lines, specific adverts were mentioned in the discussions, such as those for Casa Tarradellas, or El Almendro’s Christmas jingle that says, Vuelve a casa por Navidad [come home for Christmas], and other jingles like Las muñecas de Famosa [the Famosa dolls], or El negrito de Colacao [the little black colacao boy]. Thus, the participants pointed out that if an advert is not entertaining, it will not graba the attention of the viewer: «Since it bores me, I’m not interested in listening to what it’s saying either» (Participant 5, Group 1). Likewise, the participants also recalled very creative advertisements from their youth, yet only the narrative, and not the product or brand being promoted: «We remember the song, the actor and the story, but we don’t remember the brand. And I’ll tell you something else; I wasn’t even old enough to drive at that time…» (Participant 4, Group 2). Consequently, what stands out is that the women emphasize the target audience of the advert, and claim that a person can remember a commercial, but not necessarily the brand if it is not aimed at them as a potential consumer: «Of course, I wasn’t the target audience for everthing I saw, because some things just couldn’t be sold to a 13-year-old girl. So, I focused on the young girl in the ad who was driving the car, because she was perfect, and she had a piercing, and she was super cool» (Participant 2, Group 2).

However, despite the nostalgic mood of the discussions when recalling childhood adverts, the conversation took on a critical tone when the participants started to assess current children’s advertising. In this regard, both groups highlighted the fact that advertising directed at children today is aggressive and manipulative in relation to the products it offers. For example, some participants made comments such as, «forced and oppressive» (Participant 5, Group 1), or «it’s horrible, because you have a certain age, criteria, and experience, but they…» (Participant 3, Group 2). As a result, the participants stress the need to have enough critical thinking skills in order to challenge or judge an advertising message, which is something their children do not yet have as they are still developing. They are concerned that advertising might influence their children’s personality or lifestyle. Given the context, debates arose in the groups about gender roles in current advertisements, as well as advertising’s effect on eating habits and the claims made in this regard, and adverts that push the sale of toys. In fact, further on toy advertising, the mothers highlighted the fictitious simulations in adverts that show how the toy is used and what it can do, which they believe is deceptive. The problem is, their children are not able to comprehend the deception, even though the advert warns in small print that the actions of the toy are a simulation.

One of the biggest controversies among the group revolves around the food industry advertising aimed at children and the promotional techniques it uses. They believe that some products, especially processed foods, should be subjec to stricter regulations. In this regard, Participant 5 Group 2 mentions that the industry uses children’s animation as a promotional tactic, an example of which is Paw Patrol, and they believe this practice should be illegal due to its harmful effects on children's eating habits. In fact, this comment sparked a debate within the group about the dishonesty of promotional claims. The participants recalled how foods previously marketed as healthy have since been debunked by current evidence: «Making false advertising claims should be regulated and banned, because it happens... I’ve bought many things over the years and said to myself […] it was a lie» (Participant 2 Group 2). This same opinion was shared by Group 1: «Food marketing is brutal, and these companies are experts at hiding things» (Participant 4). Along these lines, the participants seem to agree that current advertisements deceive their children: «We have to explain to our kids that not everything they see is true, and that they shouldn't be disappointed. It’s just a cookie; the cookie won’t come to life or talk. We need to tell them that adverts do that to catch their attention. They’re just strategies» (Participant 4 Group 2). Thus, the mothers are evidently aware of their role as gatekeepers between advertising and their children, acting not only as the final purchasers of products, in some cases, but also as educators who explain the advertising strategies to their children so they will understand the persuasive narrative behind the promotion of a product: «We mothers have to take on this role. We have to say to them, ‘but honey, when I buy it for you, it’s not going to be like that. If you want, I’ll buy it, but it’s not going to fly on its own... it’s just food’» (Participant 4, Group 1).

As the disscusion on key aspects continued, the conversation moved toward branded content. It is worth noting that in both groups, a definition of the term advertising had to be provided, as the mothers did not initially understand what the moderator was referring to. Thus, the definition given was that advertising is «a type of content that can be entertaining, informative, educational, or emotional, which is created by brands to connect with their audience and build a long-term relationship. However, on many occasions the brand itself does not even appear in the content» (Moderator). Nevertheless, once the concept of advertising was understood, a series of discussions arose in relation to a term they had never heard before, branded content, yet with which they had routinely interacted in their daily lives, as the mothers began to recall Ybarra recipe books, Rimmel tutorials, and Campofrío short films. Once it was clearly understood that branded content has a commercial purpose, it took on a negative connotation for the participants, who become skeptical of such messages once they realised its motivation is economic: «There’s an intention behind it, of course, so I’ll just stop reading it and try to find an article from someone without economic interests behind it» (Participant 1, Group 1). This opinion was echoed by members of group 2 as well: «It loses credibility» (Participant 4). In a similar vein, when branded content is aimed at children, the mothers find it threatening to their children's integrity due to its potential influence on their habits and lifestyles:

How can we allow our children to be deceived? As our children aren’t able to distinguish it [...] it should be transparent. If the child can’t decifer the adverts, maybe they shouldn’t exist. Certain content should not be directed at kids (Participant 5, Group 2).

Consequently, if traditional advertising directed at children raises concerns, branded content is viewed even more negatively because it conceals its inherently persuasive nature. Nevertheless, the participants acknowledge that their children interact with such content on a daily basis, and it is an effective way for them to be entertained, share interests with other kids, and even learn other languages. Therefore, rather than banning this content from being viewed, the participants agree that limits on usage must be set, in addition to providing information to their children regarding the format, and monitoring what their kids watch in the media: «I watched a lot of TV when I was a kid. I liked it, but I also really liked reading. It’s about setting limits. The problem today is that parents don’t want to set limits» (Participant 3, Group 2). Likewise, Group 1 highlights the need to maintain balance in all aspects of life, whether it’s food or media consumption, since advertising is unavoidable.

Finally, regarding the creative block, participants in Groups 1 and 2 were shown Barbie and Llaollao content. In general, although both pieces were familiar, they had never realised that the content was advertising. Once they were exposed to this block, they described branded content as follows: «It’s advertising like any other, but it’s longer, and it takes the form of specific cartoon episodes» (Participant 3, Group 1). Moreover, the participants agreed that it is necessary to highlight the commercial intent behind the format more clearly: «It’s true that the brand is much more present now, but of course, it’s aimed at children, so they need to make it very clear» (Participant 5, Group 2).

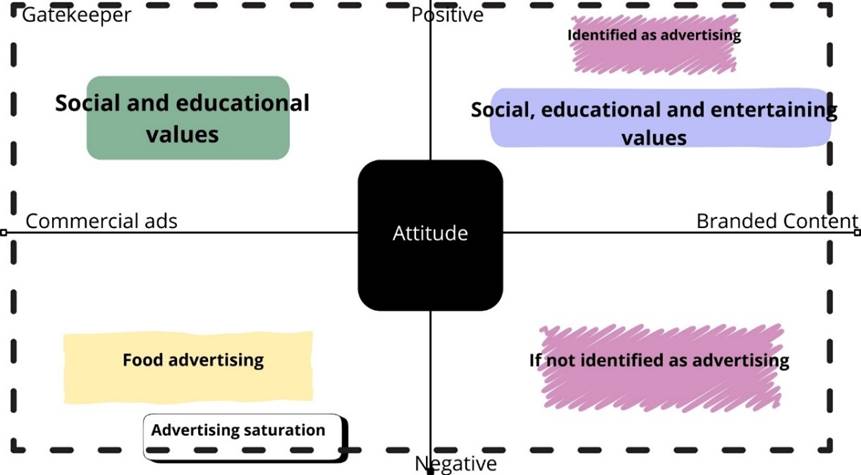

From an assessment standpoint, both pieces were seen as creative and interesting for their children. Although they have commercial interests, they are entertaining and convey morals in line with the participants' values, such as teamwork and concern for others, which appeared in the Llaollao content: «I was more focused on the frosters who were concerned about their friend not getting buried in yogurt» (Participant 4, Group 2), and «how they all managed to pull the lever through teamwork» (Participant 3, Group 2). In fact, the last observation ties in with the participants' creative exercises. In their creative sketches, they pointed out that if it were possible, they would promote social values they agree with, such as depicting girls in comfortable and casual clothing (Participant 4, Group 2). Another idea was sharing with friends: «I think it’s a beautiful idea, because you're connecting children's food with the concept of sharing» (Participant 2, Group 1). Still another idea was that it should be «interesting, entertaining, educational, and commendable» (Participant 5, Group 1). They also emphasized portraying family bonds that promote a lifestyle where spending time with the family is important: «The girl should associate the moment of consuming the product with her family, her grandmother, and her story» (Participant 1, Group 2). In summary, the attitudes toward advertising, and especially branded content, are displayed in the following infographic, where the dotted lines illustrate the overall nature of the gatekeeper in the process:

Figure 1. Infographic displaying the mothers' attitude toward advertising and branded content

Source: Prepared by the authors.

6. Discussion and conclusions

The authors feel confident in stating that the mothers who participated in this study have offered a critical analysis of advertising messages, especially when it comes to children's advertising. Thus, in line with the definition of advertising literacy provided by Livingstone & Helsper, the participants demonstrated «the ability to critically analyse and assess advertising, including understanding advertising messages, the techniques used, and the ultimate goal of advertising» (2006: 145). Nevertheless, the fact is that branded content was not initially recognized as advertising by the participants, which indicates that some types of advertising are easier to discern than others. We will now give the reader a detailed description of the main findings of the study.

Firstly, it bears mentioning that advertising has a negative perception when it is seen as invasive in terms of quantity. The participants believe that a lower volume of advertising would be more appealing to them, which is in line with other studies on the perception of advertising saturation (Casero-Ripollés, 2009; Martínez-Martínez et al., 2017). Consequently, they believe that current legislation is lax with regard to regulating the advertising industry, especially in relation to the food industry. Generally speaking, there is a tendency among the groups analyzed to judge contemporary advertising negatively, both in terms of quantity, as well as narrative quality. However, this is not the case when they reminise about advertisements from their childhood, which are recall with nostalgia. Furthermore, the effectiveness of jingles in recalling ads is worth highlighting (the ad recall factor), which is in line with other research conducted on this topic (Taylor, 2015; Taher & El Badway, 2022).

Secondly, with regard to the perception of advertising in their role as mothers, it has been observed that the participants act as gatekeepers. Thus, although the mothers might not initially know the nature of those who transmit branded content, they act as filters by assessing and explaining the content to their children. These results contrast with those found by Cornish (2014), who argues that mothers can only act as gatekeepers if they are familiar with the advertising format beforehand. Therefore, even if their children may have moments of watching television or other digital media alone, the mothers discuss, evaluate, and explain the ads to their children, breaking down the various advertising strategies used to promote products. This is consistent with the findings of Haywood & Sembiante (2023), who found that proper media education of parents leads to healthy media socialization of children. Thus, the results of this study are consistent with those of Oates et al., (2014) and Dens et al., (2007), who identified the gatekeeper’s role, and in their case the focus was on food advertising aimed at children. Regarding the food industry, this sector received the most criticism in our study, with mothers believing that more regulation, or even a ban on promotion, is necessary. These observations are supported by scientific evidence. For example, in the meta-analysis conducted by Meléndez-Illanes et al., (2022), it has been noted that unhealthy food brands are recalled and recognised to a larger extent by children than other categories.

Lastly, while the participants had previously interacted with branded content, they had not realised it was commercially motivated. In this regard, the participants believed that the absence of the brand, the entertaining narrative, and the playful nature of the format indicated that it was not an advertisement. Although initially hesitant, the participants believe that branded content is a good way to reach audiences. However, they believe it should be more clearly labeled as advertising, especially in the case of branded content aimed at children. In this regard, the materials that comprise branded content correlate with what the mothers would use if they were designing children's advertising: educational content, social values, and the promotion of a healthy lifestyle.

We believe this research offers valuable insight into mothers' perception of advertising directed at children. Therefore, we propose that future research should include the opinion of fathers as well, in order to explore how they, together with mothers, perceive and manage advertising directed at their children. Such research would provide a more comprehensive view of family dynamics in receiving advertising messages. Finally, the authors feel it would also be relevant to expand the scope of the study and conduct cross-national comparisons between countries, especially through the use of quantitative techniques that would allow the results obtained to be extrapolated to other regions of the world.

Ethics and transparency

Conflict of Interest

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions

|

Contribution |

Author 1 |

Author 2 |

Author 3 |

Author 4 |

|

Conceptualization |

x |

|

|

|

|

Data curation |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Formal Analysis |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Funding acquisition |

|

|

|

|

|

Investigation |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Methodology |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Project administration |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Resources |

|

x |

|

|

|

Software |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Supervision |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Validation |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Visualization |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Writing – original draft |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Writing – review & editing |

x |

x |

|

|

References

Aufderheide, P. (1993). Media literacy: A report of the national leadership conference on media literacy. The Aspen Institute.

Carlson, J.; Rahman, M.M.; Taylor, A. & Voola, R. (2019). Feel the VIBE: examining value-in-the-brand-page-experience and its impact on satisfaction and customer engagement behaviours in mobile social media. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 46, 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.10.002

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2009). La implantación de la TDT en España. Transformaciones en la publicidad televisiva, Telos, 79(1), 1-13. http://surl.li/pqvfbi

Cornish, L. (2014). ‘Mum, can I play on the internet?’: Parents’ understanding, perception and responses to online advertising designed for children. International Journal of Advertising, 33(3), 437–473. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-33-3-437-473

Daems, K. De Pelsmacker, P., & Moons, I. (2017). Advertisers' perceptions regarding the ethical appropriateness of new advertising formats aimed at minors. Journal of Marketing Communications, 25(4), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2017.1409250

Daems, K.; De-Pelsmacker, P. & Moons, I. (2017). Co-creating advertising literacy awareness campaigns for minors. Young COnsumers, 18(1), 54–69. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-09-2016-00630

De-Jans, S.; Hudder, L. & Cauberghe, V. (2017). Advertising literacy training: The immediate versus delayed effects on children’s responses to product placement. European Journal of Marketing, 51(11-12), 2156-2174. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-08-2016-0472

De-Jans, S.; Hudders, L. & Cauberghe, V. (2020). Is advertising child's play? A comparison of advertising literacy and advertising effects for traditional and online advertising formats among children. Tijdschrift Voor Communicatiewetenschap, 48(3), 136-165. https://doi.org/10.5117/2020.048.003.002

De-Jans, S.; Hudders, L.; Herrewijn, L; Van Geit, K. & Cauberghe, V. (2024). Serious games going beyond the Call of Duty: Impact of an advertising literacy mini-game platform on adolescents’ motivational outcomes through user experiences and learning outcomes. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 13(2), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2019-2-3

De-Pauw, P.; De-Wolf, R.; Hudders, L. & Cauberghe, V. (2018). From persuasive messages to tactics: exploring children’s knowledge and judgement of new advertising formats. New Media & Society, 20(7), 2604–2628. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817728425

Dens, N.; De Pelsmacker, P. & Eagle, L. (2007). Parental attitudes towards advertising to children and restrictive mediation of children's television viewing in Belgium. Young Consumers Insight and Ideas for Responsible Marketers, 8(1), 7-18. https://doi.org/10.1108/17473610710733730

Feijoo, B. & Sádaba, C. (2022). When Ads Become Invisible: Minors’ Advertising Literacy While Using Mobile Phones. Media and Communication, 10(1), 339-349. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i1.4720

Fernández-Gómez, E.; Segarra-Saavedra.J. & Feijoo, B. (2023). Alfabetización publicitaria y menores. Revisión bibliográfica a partir de la Web of Science (WOS) y Scopus (2010-2022). Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 81, 1-23. https://www.doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2023-1892

Finch, H. & Lewis, J. (2013). Focus Groups. In J. Ritchie, J. Lewis. C. McNaughton, C. Ormston (Eds.), Qualitative Research Practice. A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers (pp. 98-134). Sage.

García-Estévez, N. & Cartes-Barroso, M.J. (2022). The branded podcast as a new brand content strategy. Analysis, trends and classification proposal. Profesional De La Información, 31(5). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.sep.23

Haywood, A., & Sembiante, S. (2023). Media literacy education for parents: A systematic literature review. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 15(3), 79-92. https://doi.org/10.23860/JMLE-2023-15-3-7

Helme-Guizon, A. & Magnoni, F. (2019). Consumer brand engagement and its social side on brand-hosted social media: how do they contribute to brand loyalty? Journal of Marketing Management, 35(7-8), 716–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2019.1599990

Hudders, L.; De-Pauw, P; Caubergue, V.; Panic, C.; Zaourali, B.: Rozendaal, E. (2017). Shedding new light on how advertising literacy can affect children’s processing of embedded advertising formats: A future research agenda. Journal of Advertising, 46(2), 333–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1269303

Jones, S.C.; Mannino, N, & Green, J. (2010). ‘Like me, want me, buy me, eat me’: relationship-building marketing communications in children’s magazines. Public Health Nutrition, 13(12), 2111–2118. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980010000455

Kitzinger, R. & Barbour, J. (1998). Developing Focus Group Research: Politics, Theory and Practice. Sage.

Krueger, R.A. (1997). Focus Group: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Sage.

Krueger, R.A. (1998). Analying & reporting focus group results. Sage.

Livingstone, S. & Helsper, E.J. (2006). Parental Mediation of Children’s Internet Use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 52(4), 581-599. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150802437396

Mallinckrodt, V. & Mizerski, D. (2007). The effects of playing an advergame on young children’s perceptions, preferences, and requests. Journal of Advertising, 36(2), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091‐3367360206

Malmelin, N. (2010). What is Advertising Literacy? Exploring the Dimensions of Advertising Literacy. Journal of Visual Literacy, 29(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/23796529.2010.11674677

Martínez-Martínez, I.J.; Aguado, J.M. & Boeykens, Y. (2017). Implicaciones éticas de la automatización de la publicidad digital: caso de la publicidad programática en España. Profesional De La Información, 26(2), 201–210. http://surl.li/dospet

Meléndez-Illanes, L.; González-Díaz, C. & Álvarez-Dardet, C. (2022) Advertising of foods and beverages in social media aimed at children: high exposure and low control. BMC Public Health 22(1), 1795. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14196-4

Morgan, D. (1997). Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. Sage.

Muntinga, D.G.; Moorman, M. & Smith, E.G. (2011). Introducing COBRAs: exploring motivations for brand-related social media use. International Journal of Advertising, 30(1), 13–46. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-30-1-013-046

Oates, C.; Newman, N. & Tziortzi, A. (2014). Parent’s beliefs about, and attitudes towards, marketing to children. In M. Blades, C. Oates, F. Blumberg, & B. Gunter (Eds.), Advertising to children: New directions, new media (pp. 115–136). Springer.

Pérez-Sánchez, R.; López-García, X. & Ferri-García, R. (2021). Alfabetización publicitaria y consumo responsable: Evaluación de la efectividad de un programa educativo. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 78, 303-319. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2021-1496

Powell, R.M. & Gross, T. (2018). Food for Thought: A Novel Media Literacy Intervention on Food Advertising Targeting Young Children and their Parents. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 10(3), 80-94. https://doi.org/10.23860/JMLE-2018-10-3-5

Rozendaal, E.; Lapierre, M.A.; Van Reijmersdal, E.A. & Buijzen, M. (2011). Reconsidering advertising literacy as a defense against advertising effects. Media Psychology, 14(3), 333–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2011.620540

Rozendaal, E.; Slot, N.; Van Reijmersdal, E.A. & Buijzen, M. (2013). Children’s responses to advertising in social games. Journal of Advertising, 42(2/3), 142–154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2013.774588

Schivinski, B.; Christodoulides, G. & Dabrowski, D. (2016). Measuring consumers’ engagement with brand-related social-media content. Journal of Advertising Research 56(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2016-004

Scott, L. (1994) 'The bridge from text to mind: adapting reader-response theory to consumer research', Journal of Consumer Research, 21, 461-480. https://doi.org/10.1086/209411

Taken-Smith, K. (2019). Mobile advertising to digital natives: Preferences on content, style, personalization, and functionality. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 27(1), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2017.1384043

Taken-Smith, K. (2022). Mobile advertising to Hispanic digital natives. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 34(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2021.1911014

Taylor, C.R. (2015). The imminent return of the advertising jingle. International Journal of Advertising, 34(5), 717–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1087117

Taher, A. & El Badway, H.Y. (2022). The value of using popular music and performers on brand and message recall in television advertising jingles. Journal of Media Business Studies, 20(4), 303–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2022.2153235

Van-Dam, S. & Van Reijmersdal, E. (2024). Insights in adolescents’ advertising literacy, perceptions and responses regarding sponsored influencer videos and disclosures. Cyberpsychology. Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 13(2), https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2019-2-2