index●comunicación

Revista científica de comunicación aplicada

nº 15(1) 2025 | Pages 125-149

e-ISSN: 2174-1859 | ISSN: 2444-3239

Swipe or Subscribe: Do Young People Really Prefer an Ad-free Instagram?

Pasar o pagar: ¿Prefieren los jóvenes

un Instagram sin anuncios?

Received on 13/09/2024 | Accepted on 20/11/2024 | Published on 15/01/2025

https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/15/01Pasaro

Carolina Sáez-Linero | University Pompeu Fabra

carolina.saez@upf.edu | https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5116-3606

Isabel Rodríguez-de-Dios | University of Salamanca

isabelrd@usal.es | https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2460-7889

Mònika Jiménez-Morales | University Pompeu Fabra

monika.jimenez@upf.edu | https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4977-0722

Abstract: In 2023, European Instagram users faced a choice: pay a subscription fee to avoid advertisements or consent to the use of their data for targeted advertising. This study examines how Generation Z engages with personalised advertising and privacy concerns, focusing on Instagram's new subscription model. An online survey of 479 young people aged 14 to 24 revealed that only 12.5% would be willing to pay for a subscription. Although many of the participants find advertising overwhelming and distracting and express significant concerns about data protection in social media use, neither advertising saturation nor privacy concerns appear to influence their willingness to subscribe. These findings support the theory of the privacy paradox and underscore the need for new strategies to address data privacy concerns among younger users.

Keywords: Youth; Advertising; Personalisation; Privacy; Instagram.

Resumen: En 2023, los usuarios europeos de Instagram tuvieron que decidir entre suscribirse para evitar anuncios o permitir el uso de sus datos para recibir publicidad. Este estudio examina cómo la Generación Z se enfrenta a la publicidad personalizada y cuáles son sus preocupaciones respecto a la privacidad de sus datos en el contexto del nuevo modelo de suscripción de Instagram. Para ello se llevó a cabo una encuesta en línea a 479 jóvenes de 14 a 24 años que reveló que solo el 12,5% estaría dispuesto a pagar una suscripción. A pesar de considerar que la publicidad es abrumadora, que les distrae y que el uso de redes sociales conlleva un riesgo considerable para la protección de datos, ni la saturación publicitaria ni las preocupaciones de privacidad parecen influir en su disposición a pagar. Estos hallazgos refuerzan la teoría de la paradoja de la privacidad y destacan la necesidad de nuevos enfoques para abordar las inquietudes sobre privacidad de los más jóvenes.

Palabras clave: Jóvenes; publicidad; personalización; privacidad; Instagram.

To quote this work: Sáez-Linero, C., Rodríguez-de-Dios, I. & Jiménez-Morales, M. (2025). Swipe or Subscribe: Do Young People Really Prefer an Ad-free Instagram? index.comunicación, 15(1), 125-149. https://doi.org/10.62008/ixc/15/01Pasaro

1. Introduction

Generation Z (Gen Z) is the first generation to have lived their entire lives with digital technology. People born between 1995 and 2010 are what are considered digital natives and consume more content on their mobile devices than any other social group, making them extremely important for marketers. Older Gen Z members hold substantial purchasing power, while their younger peers strongly influence family spending and consumption (Van den Bergh et al., 2024).

Social media is the ideal channel for brands to reach young audiences, hence advertising plays a prominent role in the kind of digital content that Gen Z consumes (Djafarova & Bowes, 2021). According to WARC Media's Global Advertising Trends report, social media has cemented its position as the «largest media channel worldwide by advertising investment». In 2024, of the €686.5 billion spent in the digital advertising market, more than 40% is expected to be spent on social media (WARC, 2023).

Social media is particularly attractive as an advertising medium because it offers highly interactive platforms and precise audience segmentation (WARC, 2023), and hence the potential for personalised advertising, whereby content can be tailored to individual consumer preferences and characteristics (Strycharz et al., 2019). This process relies on extensive data collection practices that track users’ online behaviour, preferences, and interactions (Zuboff, 2019).

Through the use of sophisticated algorithms and access to vast amounts of data, social media platforms are not only able to deliver highly personalised ads but also provide detailed metrics that can be used to make real-time adjustments to advertising strategies. Personalisation is not only possible but essential in today’s digital advertising landscape (Chandra et al., 2022). By matching users’ preferences, personalised advertising reduces cognitive load, thus fostering more positive consumer responses, attention, engagement and favourable attitudes (De Keyzer et al., 2022; Li et al., 2014; Maslowska et al., 2016; Walrave et al., 2018).

However, the positive effect of personalised advertising are often diminished by privacy concerns around the large amounts of consumer data required for personalisation (Gironda & Korgaonkar, 2018), making consumers increasingly wary of how their data is used and potentially misused (Kim & Jeong, 2023; Segijn et al., 2021).

This duality has is the root of the so-called privacy paradox (Chan, 2024; Zhu & Chang, 2016), which reflects the discrepancy between consumers' expressed concerns about how their data is collected and used and their ongoing engagement with personalised content that precisely relies on such extensive data collection (Barnes, 2006; Norberg et al., 2007).

While privacy concerns have captured scholarly attention, personalised advertising also raises other significant issues, such as the potentially harmful targeting of vulnerable consumers, manipulation of behaviour, perpetuation of stereotypes, and issues of discrimination and bias (Bol et al., 2020; Chua et al., 2020; Dalenberg, 2018; Esteves & Resende, 2016; Fourberg et al., 2021; 2017; Sweeney, 2013).

These risks are particularly concerning when advertisements are directed at younger audiences. Research on children's exposure to advertising on mobile phones shows how these ads are significantly shaped by factors such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status, potentially exacerbating inequalities and contributing to health disparities (Radesky et al., 2020; Feijóo & Sádaba, 2022).

In this context, teenagers and young adults are frequently targeted by advertisers (Waggoner et al., 2019), and such exposure has been associated with higher levels of substance use and other unhealthy behaviours (Jackson et al., 2018; Radesky et al., 2020).

Today's youth exhibit distinct behaviours toward advertising. Unlike previous generations, they do not reject brands outright but instead choose content that aligns with their interests (Feijóo et al., 2020). In an on-demand media environment, they also show a preference for immersive advertising that blends seamlessly into their digital experiences. They are more inclined towards formats that blur the lines between marketing, entertainment, and information, and therefore feel less intrusive (Feijóo & Fernández, 2024). However, the seamless integration of advertising into content poses challenges for critical assessment, as these blurred boundaries can obscure the persuasive intent of such messages, reducing the likelihood of critical cognitive processing (van Reijmersdal & Rozendaal, 2020; Schwemmer & Ziewiecki, 2018).

Although such integrated formats make advertising harder to recognise, this generation has developed a more critical and sceptical stance toward persuasive messages in general (Roth-Cohen et al., 2022). However, their critical reasoning abilities are not yet fully developed, making them especially vulnerable to the impact of advertising on their attitudes (Packer et al., 2022). Furthermore, their scepticism toward advertising can weaken when the content is perceived to add value (Martínez, 2019) or when they feel in control of how it integrates into their routines (Feijoo & Sádaba, 2022).

Adolescents also exhibit inadequate knowledge about data collection for commercial purposes. Their views are often based on popular theories—partial or inaccurate representations of reality—about how and why their personal information is collected (Holvoet et al., 2022). This understanding gradually improves as they get older, but does not reach adult levels until around the age of 20 (Zarouali et al., 2020). Consequently, adolescents make limited use of privacy-protection strategies to counter targeted advertising (Zarouali et al., 2020), and their responses are often ineffective as they are shaped by these erroneous popular theories (Holvoet et al., 2022).

1.1. Personalised Advertising and legislative efforts in the European Union

The challenges young people face in critically assessing and engaging with personalised advertising have raised significant regulatory concerns, particularly in terms of data protection. Their limited understanding of privacy rights and their ineffective strategies for managing personal data underscore the need for regulatory measures aimed at addressing these vulnerabilities. A prominent example of such efforts is the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which was designed to give individuals greater control over their personal data and establish stricter standards for its processing by companies.

One of the most notable applications of the GDPR occurred in November 2023, when the Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC) ruled that Meta—the technology conglomerate whose European headquarters are in Dublin—employed practices for collecting and using personal data to display personalised ads that violated the GDPR.

This decision significantly impacted Meta, whose core business model is based on targeted advertising. The ruling required the company to cease using personal data for such purposes without explicit user consent, but did allow Meta to introduce a paid subscription model, with the free version functioning as a form of consent.

The European measure is designed to empower users regarding the way their data is handled. However, there is no clear evidence as to whether users perceive this alternative as a means of safeguarding their data or merely as a way to avoid advertisements. Especially among younger users, whose understanding of data protection and privacy rights may be somewhat under-developed, the effectiveness of such regulatory efforts is potentially limited (Stoilova et al., 2019).

This research looks at how young Instagram users navigate personalised advertising and privacy. Specifically, it explores their reactions to Instagram's new subscription model, which allows users to avoid advertisements by preventing data profiling. This general goal is broken down into the following specific objectives:

O1. To examine young people's perceptions of the prevalence, appropriateness, and impact of personalised advertising on social media.

O2. To identify the strategies young people use to avoid ads.

O3. To assess young people's general online privacy concerns.

O4. To understand the strategies young people employ to cope with privacy concerns.

O5. To evaluate the reception of Instagram’s new subscription model to avoid advertising and prevent data profiling, and also determine which dimensions predict subscription intent.

2. Methodology

The study involved 479 respondents to a self-administered online survey conducted in late November 2023, coinciding with the introduction of Instagram's requirement for users to choose whether or not to switch to a paid subscription model. The survey targeted young individuals in Spain and employed a random sampling method.

This sample size was selected to ensure sufficient precision for estimating population parameters. The total population is approximately 5.4 million (INE, 2022). A confidence level of 95% was applied, with a corresponding margin of error of ±4.48%, calculated using the most conservative estimate (p = 0.5) to provide a robust range for all reported proportions. A margin of error of up to ±5% is widely recognised as acceptable in the literature (Phillips et al., 2013), further validating its suitability for the purposes of this study. The sample size also enables reliable subgroup analyses and supports the statistical tests applied in this research.

The survey was conducted via an online panel, and participants were compensated for their time. Before deployment, it received ethical approval from the Ethical Committee of Pompeu Fabra University and was tested with volunteers to ensure the clarity and comprehension of the questions. Details of the questionnaire can be found in Appendix I.

The respondents were all members of Generation Z. Most of the sample (90.63%) were aged between 18 and 24, and the remaining 44 respondents (9.17%) were minors aged 14 to 17. The gender distribution was as follows: 160 respondents (33.40%) identified as male, 307 (64.09%) as female, and nine (1.88%) as non-binary. Three respondents (0.63%) either preferred not to disclose their gender or did not provide a response.

While the sample was not designed to be representative of the entire population, the proportion of females (60%) and males (40%) does not diverge significantly from the demographic distribution of Instagram users in the 18-24 age group, where women account for 53.1% and men for 46.9% (Statista, 2024a). Although specific data for minors is unavailable due to privacy regulations, research highlights that teenage girls (66%) are more likely than their male peers (53%) to use Instagram (Pew Research Center, 2023).

2.1 Measures

The participants were asked to self-report their weekly Instagram usage from 0 to 10 hours, to assess whether more intensive use is a potential justification for investing in the subscription model. They also rated their perception of the volume of ads appearing on Instagram, thus providing an initial impression before further exploration of their perceptions of advertising on this platform.

The participants were also asked if they preferred to pay €12.99 a month for an ad-free Instagram, or were happier to use the free version with ads that utilise their information for advertising purposes. The question used the exact wording employed by the platform to ask users to choose between the two models (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Screenshot of the presentation of the subscription option

Source: Instagram

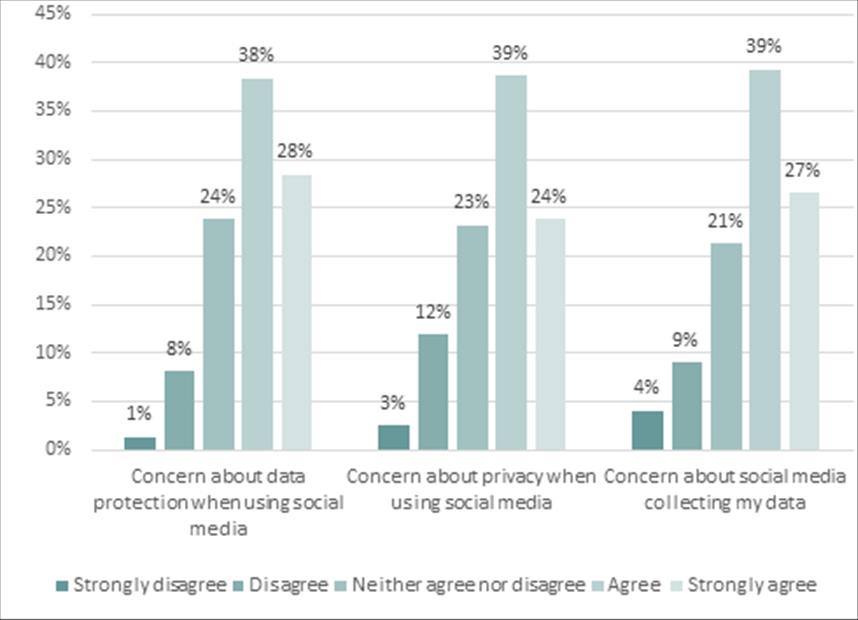

We also adapted the scales proposed by Stubenvoll et al. (2024) to measure perceived personalisation, overload from personalised advertising, and privacy concerns regarding social media. More concretely, to gauge perceived personalisation (rho [1]= .55, M = 3.53, SD = .85), the participants rated two items: «Ads in my social media seem to be tailored to me» and «Ads in my social media are aimed directly at people like me». For the sense of overload from personalised advertising (rho = .29, M = 3.56, SD = .87), we employed «I often feel like there are too many ads on my social media» and «I often get distracted by the excessive number of ads I see on my social media». To assess the participants' privacy concerns about personalised advertising (Cronbach’s α = .60, M = 3.76, SD = .76), we used «The use of social media carries a considerable data protection risk», «I worry about my privacy when I use social media», and «I am concerned that data is collected on social media». All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating the lowest level of agreement and 5 indicating the highest, and then averaged.

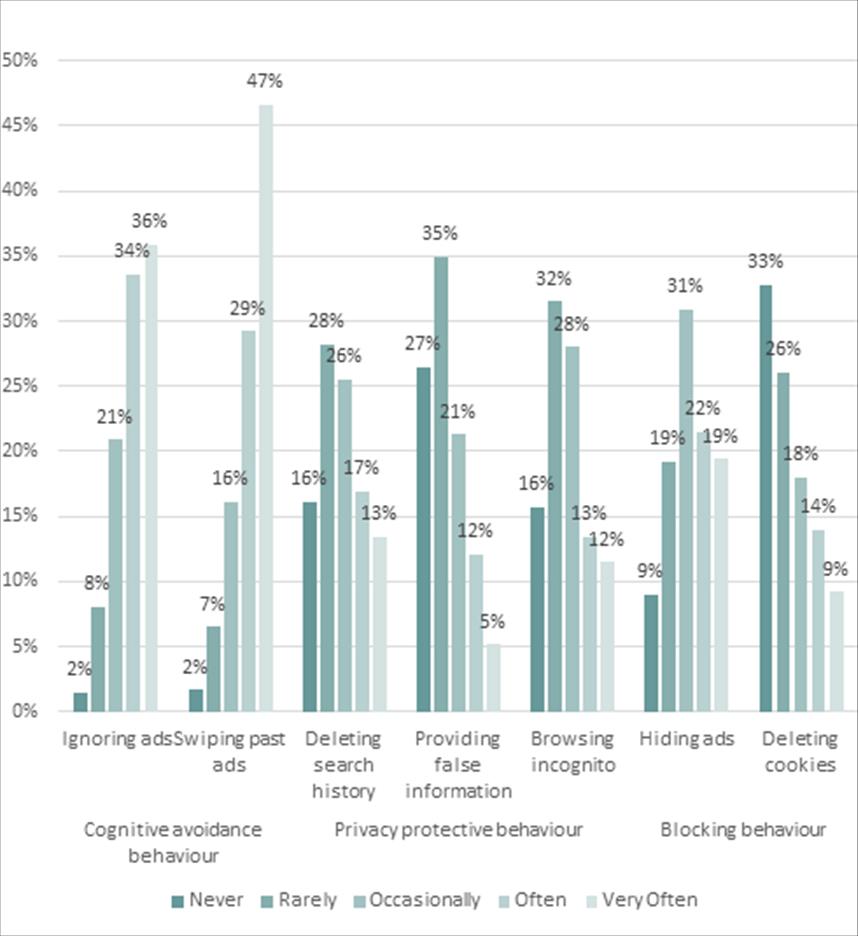

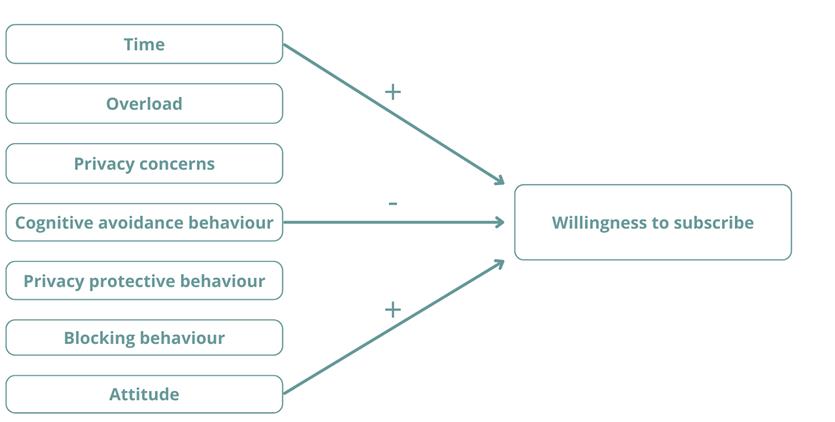

We operationalised the strategies young people employ to cope with privacy concerns into three categories: cognitive avoidance behaviour, privacy-protective behaviour and blocking behaviour. These categories capture the different ways in which young users respond to personalised advertising and privacy concerns (Stubenvoll et al., 2024). All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often) and then averaged to calculate a single value for each measure.

For cognitive avoidance behaviour (rho = .65, M = 4.03, SD = .91), we adapted Dodoo and Wen’s (2019) and Stubenvoll et al.’s (2024) scales to two items: «I ignore ads on my social media» and «I scroll down when I see ads on my social media to avoid them». To measure privacy-protecting behaviour (α = .61, M = 2.64, SD = .90), we derived a 3-item scale from Boerman et al. (2021): «I delete my browser history»; «I fill in false information about myself (for instance, a fake name or incorrect date of birth) when asked for such information» and «I use the private mode in my browser». Finally, we based blocking behaviour on Dodoo and Wen’s (2019) and Stubenvoll et al.’s (2024) scale, employing «I have clicked “hide” an ad» and «I usually delete cookies from my browser» (rho = .30, M = 2.82, SD = 1.02).

Finally, we used four items to measure attitudes towards targeted advertising, adapting Smit et al.’s (2014) scale to new social media advertising options: «I choose to have ads personalised to me»; «I have reported an ad as inappropriate»; «I have searched for information on why an ad appears», and «I use an ad blocker». The items were rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). After re-coding, they were averaged to represent the attitude toward targeted ads, with higher scores representing a more positive one (α = .69, M = 3.46, SD = .72).

3. Results

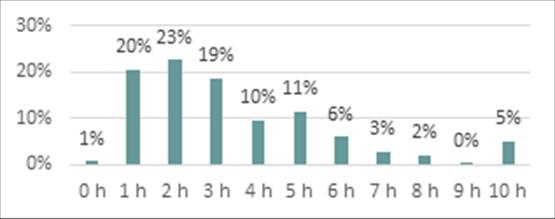

Most respondents reported using Instagram for an average of 1 to 3 hours per day, with 20.46% using it for 1 hour, 22.55% for 2 hours, and 18.56% for 3 hours. Usage beyond this range declines, with only 5.01% of participants using it for 10 hours a day (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Daily hours spent on Instagram

Source: Provided by the authors

To examine young people's perceptions of the prevalence, appropriateness, and impact of personalised advertising on social media, we explored several dimensions. The majority of respondents (57.20%) believe that «quite a few» ads appear on Instagram, while 26.72% think there are «few» ads, 15.03% perceive «many» ads, and only 1.04% believe there are no ads at all.

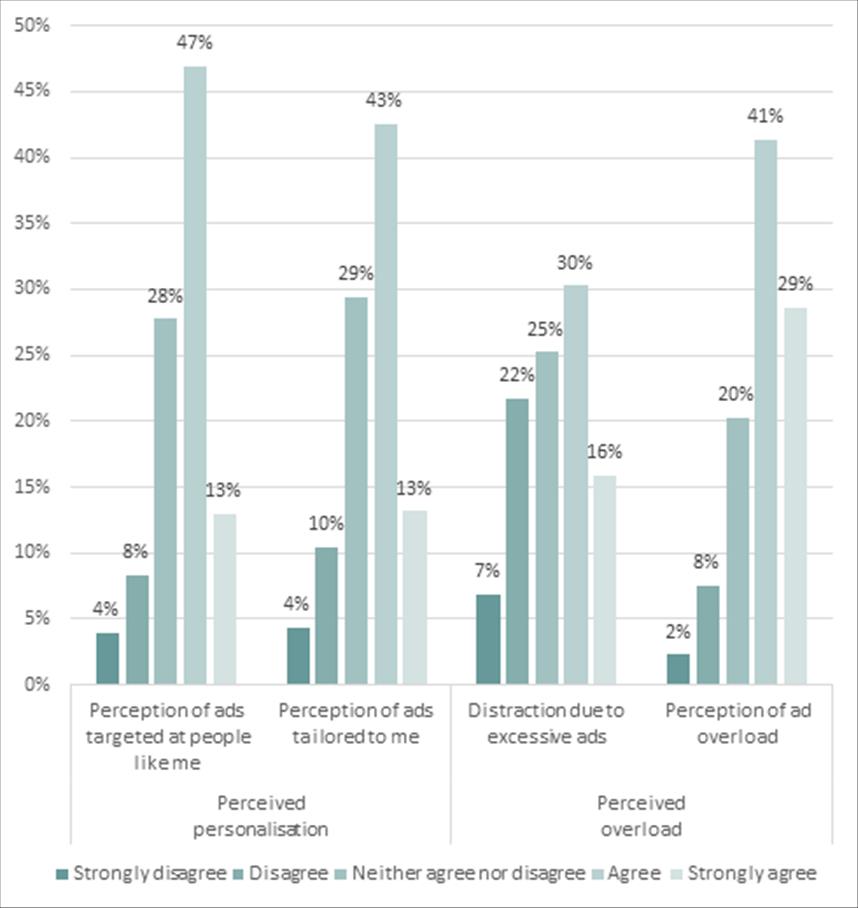

As shown in Figure 3, 41.34% of respondents agree, and 28.60% strongly agree that they experience ad overload. Meanwhile, 30.27% agree, and 15.87% strongly agree that excessive ads are distracting. Regarding personalisation, a significant proportion of respondents agree (42.59%) or strongly agree (13.15%) that they encounter ads specifically tailored to them on social media. Similarly, 46.97% agree, and 12.94% strongly agree that ads are targeted at people like them.

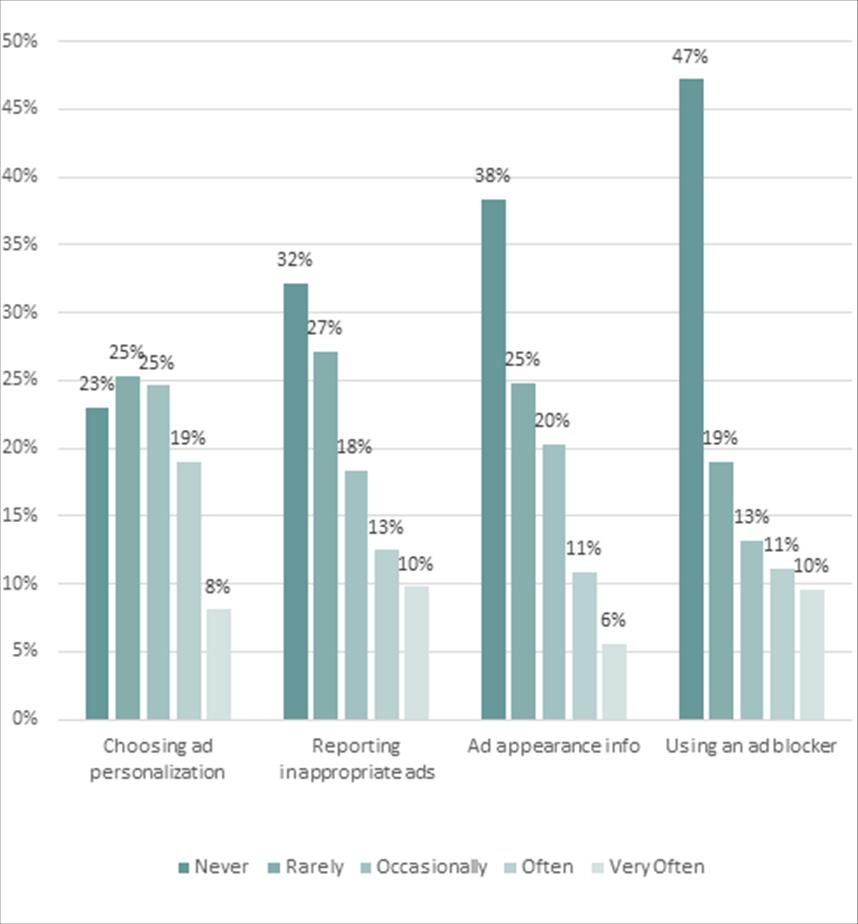

The findings reveal diverse attitudes toward personalised advertising among young people. Actions such as reporting inappropriate ads and seeking information about why an ad appears are relatively uncommon. Specifically, 32.2% of respondents never report inappropriate ads, 38.4% never seek information about why an ad appears, and 23.0% of respondents never adjust the ad personalisation settings. The respondents are not especially inclined to use ad blockers, with 47.2% never using one, and 19.0% rarely doing so (see Figure 4).

Figure 3: Perception of ad personalisation and overload

Source: Provided by the authors

Figure 4: Attitudes towards personalised advertising

Source: Provided by the authors

As for how the young respondents deal with ads, the findings reveal that they very often ignore (35.9%) or swipe past (46.6%) them. Hiding ads is another frequent tactic, used often by 21.5% and very often by 19.4% (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Behaviours for coping with personalised ads and privacy

Source: Provided by the authors

Most respondents express significant concerns about privacy and data protection. 38.4% agree, and 28.4% strongly agree that using social media poses a risk in this regard. Concerns about privacy and data collection are also high, with 38.6% agreeing, 23.8% strongly agreeing that privacy is a worry, and 39.2% agreeing, and 26.5% strongly agreeing that they are concerned about social media collecting their data (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Privacy concerns

Source: Provided by the authors

Finally, regarding strategies for coping with privacy concerns (see Figure 5), the results suggest that more active interventions are uncommon. 16.1% of respondents never delete their browsing history and 28.2% do so rarely. And 26.5% never provide false personal information and 34.9% rarely do so. 28.0% of respondents say they browse incognito, but while 32.8% never delete their cookies, others do engage in this activity with varying frequency.

2.2 Identifying predictors of subscription willingness

A binomial logistic regression was performed to evaluate reception of Instagram’s new subscription model that offers an ad-free experience and protection against data profiling. First, mean values were calculated for each dimension in the analysis. The logistic regression model was statistically significant, X2 (12, N = 479) = 33.534, p < .001, explaining 13% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in the likelihood of paying and correctly classified 87.5% of cases.

Three factors were identified as predictors of this variable (see Figure 7). The only factor that positively predicts willingness to subscribe is time spent on Instagram, b = .13, Wald χ² (1) = 5.49, p = .019. A greater amount of time spent on Instagram is associated with a 14% increase in the likelihood of paying for a subscription (OR=1.143, 95%CI [1.02, 1.28]). On the other hand, cognitive avoidance behaviours towards ads (ignoring and swiping) negatively predict willingness to pay, b = -.37, Wald χ² (1) = 5.24, p = .022. Each unit of increase in cognitive avoidance behaviour is associated with a 30.9% decrease in the odds of paying for a subscription (OR=.691, 95%CI [.503, .948]). Likewise, a positive attitude towards targeted advertising negatively predicts willingness to pay, b = -.50, Wald χ² (1) = 4.275, p = .039. Each unit of increase in a positive attitude towards targeted advertising is associated with a 39.1% decrease in the odds of paying to subscribe to an ad-free Instagram.

Figure 7: Predictive model for determining subscription willingness

Source: Provided by the authors

The analysis also indicated that gender is a predictor of willingness to subscribe. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that men are significantly more willing to pay for an ad-free Instagram experience, F (3, 475) = 3.564, p = .014. Specifically, 19.4% of men were willing to pay the fee, compared to 9.1% of women and 11.1% of non-binary participants.

4. Discussion and conclusions

This study has explored how Generation Z deals with personalised advertising and privacy concerns on social media, focusing specifically on the reactions of Spanish participants aged 14 to 24 to Instagram's new ad-free subscription model.

The findings suggest that most young people pay little attention to advertising on social media, which aligns with prior research, including Feijóo et al. (2024), who studied children aged 10 to 14, also in Spain. They found that 52.8% of their youngest group ignore mobile phone advertisements, and this percentage increases with age. Similarly, we found that approximately 70% of older adolescents and young adults report that they frequently ignore social media advertisements, while 76% tend to scroll past them, and only 8% pay any attention at all to them.

Their strategies for dealing with advertising seem consistent with this low interest: 59% rarely or have never reported an ad as inappropriate, 63% rarely or have never searched for information on why an ad appeared, and 66% rarely or have never used an ad blocker. However, hiding of ads is a relatively common practice: 41% do so often or very often, and 31% do so occasionally. Accordingly, only 27% often or very often choose to allow ads to be personalised.

Interestingly, despite this apparent indifference to advertising, Generation Z is generally overwhelmed by the number of ads they encounter in their social media accounts. 70% think there are too many, and 46% often find them distracting. Specifically regarding Instagram, young individuals are acutely aware of the presence of advertisements on the platform. 57% believe they encounter a significant number, 15% perceive a high volume, and only 1% claim to see none, suggesting they either fail to even notice them, or have already paid for an ad-free account.

Young people are generally quite aware that ads are personalised for them. 56% say that they are tailor-made for them, and 60% understand how social networks use targeted advertising practices such as data profiling, and hence know that their data is being collected and processed.

This awareness extends to privacy concerns. 67% believe that social media carries a considerable risk in terms of data protection, 62% are concerned about their privacy when using social media, and 66% are uncomfortable about platforms collecting their data, thus aligning with previous findings (see Maier et al., 2023).

Paradoxically, despite their concerns, younger audiences rarely use privacy-protection strategies to counter targeted advertising, which also aligns with previous research (see Hargittai & Marwick, 2016; Zarouali et al., 2020). Specifically, 44% rarely or never delete their browser history, 26% only do so occasionally, and 59% rarely or never delete cookies. Additionally, 61% rarely or never provide false information about themselves, 48% rarely or never browse in private mode, and 28% only do so occasionally.

In keeping with this paradoxical behaviour, despite their concerns and being overwhelmed by ads, most young people are unwilling to pay for a subscription that prevents profiling and is ad-free. Only 12.5% stated that they would opt for such a service.

In our analysis, the proposed model did not perform as expected. Only three of the seven variables significantly influenced the intention to pay a subscription fee. The small percentage of participants willing to pay for a subscription, and hence low variability in the dependent variable, may have diminished the model’s statistical power, making it difficult to detect meaningful relationships.

The only factor that positively predicted willingness to subscribe was the amount of time users spend on Instagram. It would seem that the more young people use the platform, the more appealing the idea of paying for an ad-free experience becomes. While this is understandable from an ad-avoidance perspective, it is less consistent in terms of privacy, as less frequent users of Instagram are by no means exempted from being profiled.

The study also found that cognitive avoidance behaviour toward ads, such as ignoring and swiping past them, negatively predicted willingness to pay for a subscription. This suggests that users who have developed strategies to avoid ads may be less inclined to see the value of paying to remove them altogether. Furthermore, a positive attitude toward targeted advertising also negatively influenced subscription intention. As expected, users who appreciate targeted ads have no intention of opting out of them. Again, these findings are consistent from an ad avoidance perspective but make far less sense from a data protection one.

It is also interesting to note that neither privacy concerns nor privacy-protecting behaviours correlate significantly with a willingness to subscribe, suggesting that young people may not fully understand what subscribing exactly entails.

Meta’s wording when presenting the subscription option to users may impact this greater concern about advertising. The information is presented as if the key issue at stake was the decision whether or not to have a free advertising experience, while apart from a brief mention of «your info», the processing of personal data is otherwise ignored (see Figure 1).

However, Instagram's subscription model is very different to the ad-free versions of other apps, which have been shown to collect the same user data as their free ad-supported versions (Tran et al., 2021). The European legislation that prompted Meta to offer a paid version was driven by the concern that users were unaware that their data was being used for advertising purposes, and it has little to do with whether or not the platform includes advertisements. This is no small issue, since Meta collects 79.49% of all legally permissible user data, and Instagram collects 69.23% (Clario, 2022).

In our study, gender differences also emerged as a significant factor, with males being substantially more willing to pay than female and non-binary participants. Previous research suggests that women generally exhibit greater privacy concerns and engage in more protective behaviours than men (Mutambik et al., 2022; Tifferet, 2019), which does not align with our findings. This discrepancy again suggests that the decision to subscribe may not be primarily motivated by privacy concerns.

Another possible explanation for the results is the privacy paradox. This theory posits that individuals can become weary and cynical due to the constant need to manage their privacy online (Smith et al., 1996). This fatigue can lead to feelings of helplessness and a lack of control over privacy decisions, ultimately influencing online privacy behaviour. Indeed, privacy fatigue may impact online behaviour more significantly than privacy concerns (Choi et al., 2018).

Economic factors should also be considered. Meta's paid versions started at €9.99 for a web-based account and €12.99 for the app (Instagram Help Centre, n.d.). Given that, according to Statista (2024b), mobile devices are the most popular choice for digital activities among Generation Z, young people will probably be more interested in the more expensive option. Moreover, many young users have multiple accounts (Sokowati & Manda, 2022), which could significantly increase their monthly costs.

Previous research shows that young people are generally reluctant to pay for online content, primarily due to the perception of high costs (Groot Kormelink, 2023), and a «free mentality» cultivated by the internet (O'Brien, 2022). Since young people are used to ignoring and swiping past ads, their avoidance is probably not a compelling enough reason to subscribe.

Also, the free version limits the ability to advertise oneself or monetise content (Instagram Help Centre, n.d), which could affect the decisions of the many users aspiring to become influencers by promoting their content (Moubarac, 2023), an option only available to free-mode users.

In conclusion, this study underscores the paradoxical behaviour of Generation Z when it comes to personalised advertising and privacy on social media. While they are aware of the vast number of ads and the data collection involved, most opt for passive strategies, such as ignoring ads, rather than taking active steps to protect their privacy or paying for a version without data profiling and, consequently, without ads. Time spent on Instagram was the strongest predictor of subscription intent, suggesting that a smoother experience on the platform, rather than privacy concerns, drives willingness to subscribe.

This study raises important questions about whether offering a paid subscription model as an alternative to the free version meets the requirements for «informed consent». By shedding light on the low willingness of young users to pay for ad-free models and their limited understanding of the implications of both options, this research underscores the need for clearer regulatory guidelines. Platforms should be required to present both free and paid options in an unequivocal manner, ensuring that users fully understand that the free version entails not just exposure to advertisements but also data profiling.

The findings also emphasise the importance of marketing professionals addressing young people's privacy concerns. Greater efforts should be made to clearly explain what data is collected and how it is used for personalisation. Additionally, given that many young users feel overwhelmed by the sheer volume of ads, marketers should be inspired to explore alternative, less intrusive ways to engage their audience. By reducing ad overload and fostering a sense of transparency, marketers can build stronger trust and more meaningful connections with Generation Z.

5. Limitations and future research

This research contributes to the existing body of knowledge on how Generation Z engages with personalised advertising and manages its privacy concerns. Also, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first research to examine the likelihood of young people paying to use a profiling-free and ad-free version of Instagram. However, our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations.

First, the limited variation in the dependent variable may have restricted the model's ability to identify significant predictors among the seven variables examined. Future studies should consider alternative methodologies to better capture and understand the factors influencing subscription intentions. For instance, qualitative research could provide deeper insights into the barriers and motivations for subscribing, and what young people understand about the implications of such free models.

Moreover, the survey was conducted shortly after the subscription model was introduced, so some users might have still been deliberating, while others had not yet considered the option. Future research should directly ask users whether they currently pay for the subscription rather than posing hypothetical questions about their intentions. A repeat of the study now that more time has passed could yield valuable insights into users' actual behaviour and decisions.

The sample composition also entails certain limitations. As an exploratory study, it provides valuable insights, but its relatively small sample size (N = 479) and focus on a single country, Spain, limit the generalizability of the findings to other contexts. Although this concentrated approach does enable a detailed understanding of a specific demographic, future studies could include larger and more diverse samples across multiple countries and age groups. Furthermore, the over-representation of women in the sample (60%) reflects general trends in Instagram usage, but may have influenced the results. A more balanced gender distribution in future research would help capture a more diverse range of perspectives.

There may also be other, unexplored factors that influence the decision to subscribe. For instance, this study did not directly measure the subscription fee, despite it being a highly probable determinant of subscription intentions. Other potential moderating variables, such as familiarity with privacy policies or exposure to educational campaigns about privacy and digital rights, could provide further insights. Future research should explore these factors to offer a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics behind subscription decisions.

Finally, longitudinal or experimental studies could examine how privacy concerns and willingness to pay evolve over time, particularly in response to awareness campaigns on data privacy and profiling. Interviews with psychologists and experts in digital behaviour could provide deeper insights into the psychological barriers and motivations behind young people's decisions regarding data privacy and subscription. Such studies would be invaluable for assessing whether transparency, education, and tailored interventions can effectively mitigate the privacy paradox observed among younger users.

Given the legal implications of presenting paid subscriptions as an interpretation of informed consent, and the potential adoption of similar approaches by other social media platforms, a more thorough understanding of their acceptance and comprehension is essential. As regulatory frameworks increasingly aim to empower users and ensure transparency in data usage, it is becoming critical to evaluate whether such models genuinely meet legal standards or, on the contrary, merely serve as mechanisms to circumvent stricter data protection measures.

By providing a comprehensive view of these dynamics, future research could guide policymakers in refining legislation to ensure that subscription models align with ethical and legal principles. It could also inform platforms on the design of more user-centred approaches that enhance trust and engagement while respecting privacy rights in this constantly evolving digital landscape.

Ethics and transparency

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the reviewers who provided valuable feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript. The authors also extend their gratitude to Michael Roberts for his careful review of the English version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from Pompeu Fabra University (UPF). Rodríguez-de-Dios holds a Ramón y Cajal Grant (RYC2021-033612-I) funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR.

Author contributions

|

Contribution |

Author 1 |

Author 2 |

Author 3 |

Author 4 |

|

Conceptualization |

X |

|

|

|

|

Data curation |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Formal Analysis |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Funding acquisition |

X |

|

|

|

|

Investigation |

X |

|

|

|

|

Methodology |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Project administration |

X |

|

|

|

|

Resources |

X |

|

|

|

|

Software |

|

|

|

|

|

Supervision |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Validation |

|

|

|

|

|

Visualization |

X |

|

|

|

|

Writing – original draft |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Writing – review & editing |

X |

X |

X |

|

Data availability statement

The data can be requested directly from the authors.

References

Barnes, S. B. (2006). A privacy paradox: Social networking in the United States. First Monday. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v11i9.1394

Boerman, S. C., Kruikemeier, S., & Borgesius, F. J. Z. (2021). Exploring Motivations for Online Privacy Protection Behavior: Insights from panel data. Communication Research, 48(7), 953–977. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650218800915

Bol, N., Strycharz, J., Helberger, N., Van De Velde, B., & De Vreese, C. H. (2020). Vulnerability in a tracked society: Combining tracking and survey data to understand who gets targeted with what content. New Media & Society, 22(11), 1996–2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820924631

Chan, S. (2024). Data colonialism on Facebook for personalised advertising: The discrepancy of privacy concerns and the privacy paradox. Journal of Data Protection & Privacy, 6 (3), 266–282. https://doi.org/10.69554/nfsx3577

Chandra, S., Verma, S., Lim, W. M., Kumar, S., & Donthu, N. (2022). Personalization in personalised marketing: Trends and ways forward. Psychology and Marketing, 39(8), 1529–1562. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21670

Choi, H., Park, J., & Jung, Y. (2018). The role of privacy fatigue in online privacy behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 81, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.12.001

Chua, M. Y., Yee, G. O. M., Gu, Y. X., & Lung, C. (2020). Threats to online advertising and countermeasures. Digital Threats Research and Practice, 1(2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1145/3374136

Clario: Big Brother Brands Report: Which companies access our personal data the most? (2023). https://clario.co/blog/which-company-uses-most-data/

Dalenberg, D. J. (2018). Preventing discrimination in the automated targeting of job advertisements. Computer Law & Security Review, 34(3), 615–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2017.11.009

De Keyzer, F., Dens, N., & De Pelsmacker, P. (2022). Let’s get personal: Which elements elicit perceived personalization in social media advertising? Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 55, 101183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2022.101183

Djafarova, E., & Bowes, T. (2021). ‘Instagram made Me buy it’: Generation Z impulse purchases in fashion industry. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59, 102345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102345

Dodoo, N. A., & Wen, J. (2019). A path to mitigating SNS ad avoidance: tailoring messages to individual personality traits. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(2), 116–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2019.1573159

Esteves, R., & Resende, J. (2016). Competitive Targeted Advertising with Price Discrimination. Marketing Science, 35(4), 576–587. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2015.0967

Feijóo, B., & Fernández-Gómez, E. (Eds.). (2024). Advertising Literacy for Young Audiences in the Digital Age : A Critical Attitude to Embedded Formats (1st ed. 2024.). Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-55736-1

Feijóo, B., Sádaba, C., & Bugueño, S. (2020). Anuncios entre vídeos, juegos y fotos. Impacto publicitario que recibe el menor a través del teléfono móvil. Profesional de la Información, 29,e290630. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.nov.30

Feijóo, B., & Sádaba, C. (2022). Publicidad a medida. Impacto de las variables sociodemográficas en los contenidos comerciales que los menores reciben en el móvil. Index Comunicación, 12(2), 227–250. https://doi.org/10.33732/ixc/12/02public

Fourberg, N., Serpil, T., Wiewiorra, L., Goldovitch, I., De Streel, A., Jacquemin, H., Hill, J., Nunu, M., Bourguignon, C., Jacques, F., Ledger, M., & Lognoul, M. (2021). Online advertising: the impact of targeted advertising on advertisers, market access and consumer choice. https://researchportal.unamur.be/fr/publications/online-advertising-the-impact-of-targeted-advertising-on-advertis

Gironda, J. T., & Korgaonkar, P. K. (2018). iSpy? Tailored versus Invasive Ads and Consumers’ Perceptions of Personalised Advertising. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 29, 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2018.03.007

Groot Kormelink, T. (2023). Why people don’t pay for news: A qualitative study. Journalism, 24(10), 2213–2231. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849221099325

Holvoet, S., De Jans, S., De Wolf, R., Hudders, L., & Herrewijn, L. (2022). Exploring teenagers’ folk theories and coping strategies regarding commercial data collection and personalized advertising. Media and Communication (Lisboa), 10(1S2), 317–328. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i1.4704

Hargittai, E., & Marwick, A. (2016). «What can I really do?» Explaining the Privacy Paradox with Online Apathy. International Journal of Communication, 10, 21. https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-148157

INE. (2022). Población por edad (año a año), sexo y año (1998-2022). Instituto Nacional de Estadística. https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Tabla.htm?path=/t20/e245/p08/l0/&file=02003.px&L=0

Instagram Help Centre: Subscription for no ads. (n.d.). https://help.instagram.com/923021729404927

Jackson, K. M., Janssen, T., & Gabrielli, J. (2018). Media/Marketing influences on adolescent and young adult substance abuse. Current Addiction Reports, 5(2), 146–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-018-0199-6

Kim, J., & Jeong, H. J. (2023). ‘It’s my virtual space’: the effect of personalised advertising within social media. International Journal of Advertising, 42(8), 1267–1294. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2023.2274243

Li, Y., Lin, L., & Chiu, S. (2014). Enhancing targeted advertising with social context endorsement. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 19(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.2753/jec1086-4415190103

Maier, E., Doerk, M., Reimer, U., & Baldauf, M. (2023). Digital natives aren’t concerned much about privacy, or are they? I-com, 22(1), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1515/icom-2022-0041

Martínez, C. (2019). The struggles of everyday life: How children view and engage with advertising in mobile games. Convergence The International Journal Of Research Into New Media Technologies, 25(5-6), 848-867. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517743665

Maslowska, E., Smit, E. G., & Van Den Putte, B. (2016). It is all in the name: A study of consumers’ responses to personalised communication. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 16(1), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2016.1161568

Moubarac, J.-C. (2023). The social and cultural factors associated to ultra-processed dietary patterns. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 79, 160-. https://doi.org/10.1159/000530786

Mutambik, I., Lee, J., Almuqrin, A., Halboob, W., Omar, T., & Floos, A. (2022). User concerns regarding information sharing on social networking sites: The user’s perspective in the context of national culture. PloS One, 17(1), e0263157–e0263157. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263157

Norberg, P. A., Horne, D. R., & Horne, D. A. (2007). The Privacy Paradox: Personal Information Disclosure Intentions versus Behaviors. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 41(1), 100–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2006.00070.x

O’Brien, D. (2022). Free lunch for all? – A path analysis on free mentality, paying intent and media budget for digital journalism. Journal of Media Economics, 34(1), 29–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/08997764.2022.2060241

Packer, J., Croker, H., Goddings, A., Boyland, E. J., Stansfield, C., Russell, S. J., & Viner, R. M. (2022). Advertising and Young People’s Critical Reasoning Abilities: Systematic review and Meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 150(6). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-057780

Pew Research Center. (2023). Teens, Social Media and Technology. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2023/12/11/teens-social-media-and-technology-2023/

Phillips, P. P., Phillips, J. J., & Aaron, B. (2013). Survey Basics. ASTD Press.

Radesky, J., Chassiakos, Y. R., Ameenuddin, N., & Navsaria, D. (2020). Digital advertising to children. Pediatrics, 146(1), e20201681. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-1681

Roth-Cohen, O., Rosenberg, H., & Lissitsa, S. (2022). Are you talking to me? Generation X, Y, Z responses to mobile advertising. Convergence The International Journal Of Research Into New Media Technologies, 28(3), 761-780. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565211047342

Schwemmer, C., & Ziewiecki, S. (2018). Social Media Sellout: The Increasing Role of Product Promotion on YouTube. Social Media + Society, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118786720

Segijn, C., Strycharz, J., Riegelman, A., & Hennesy, C. (2021). A literature review of personalization transparency and control: Introducing the Transparency-Awareness-Control Framework. Media and Communication, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i4.4054

Smit, E. G., Van Noort, G., & Voorveld, H. A. (2014). Understanding online behavioural advertising: User knowledge, privacy concerns and online coping behaviour in Europe. Computers in Human Behavior, 32, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.11.008

Smith, H. J., Milberg, S. J., & Burke, S. J. (1996). Information Privacy: Measuring Individuals’ Concerns about Organizational Practices. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 20(2), 167. https://doi.org/10.2307/249477

Sokowati, M. E., & Manda, S. (2022). Multiple Instagram accounts and the illusion of freedom. Komunikator, 14(2), 127-136. https://doi.org/10.18196/jkm.15914

Statista. (2024a). Spain Instagram users 2024, by age and gender. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1403003/instagram-users-spain-age-gender/

Statista. (2024b). Global Gen Z online activity reach 2018, by device. https://www.statista.com/statistics/321511/gen-z-online-activity-reach-by-device/

Stoilova, M., Nandagiri, R., & Livingstone, S. (2019). Children’s understanding of personal data and privacy online – a systematic evidence mapping. Information Communication & Society, 24(4), 557–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2019.1657164

Strycharz, J., Van Noort, G., Smit, E., & Helberger, N. (2019). Protective behavior against personalised ads: Motivation to turn personalization off. Cyberpsychology Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 13(2). https://doi.org/10.5817/cp2019-2-1

Stubenvoll, M., Binder, A., Noetzel, S., Hirsch, M., & Matthes, J. (2024). Living is Easy With Eyes Closed: Avoidance of Targeted Political Advertising in Response to Privacy Concerns, Perceived Personalization, and Overload. Communication Research, 51(2), 203–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502221130840

Sweeney, L. (2013). Discrimination in online ad delivery. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2208240

Tifferet, S. (2019). Gender differences in privacy tendencies on social network sites: a meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.046

Tran, K., Tapiador, J., & Sanchez-Rola, I. (2021). Are paid apps really better for your privacy? An analysis of free vs. paid apps in Android. IMDEA Networks Institute Repository. https://dspace.networks.imdea.org/handle/20.500.12761/691

Van Den Bergh, J., De Pelsmacker, P., & Worsley, B. (2024). Beyond labels: segmenting the Gen Z market for more effective marketing. Young Consumers, 25(2), 188–210. https://doi.org/10.1108/yc-03-2023-1707

Van Reijmersdal, E. A., & Rozendaal, E. (2020). Transparency of digital native and embedded advertising: Opportunities and challenges for regulation and education. Communications, 45(3), 378-388. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2019-0120

Wagoner, K. G., Berman, M., Rose, S. W., Song, E., Ross, J. C., Klein, E. G., Kelley, D. E., King, J. L., Wolfson, M., & Sutfin, E. L. (2019). Health claims made in vape shops: an observational study and content analysis. Tobacco Control, 28(e2), e119–e125. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054537

Walrave, M., Poels, K., Antheunis, M. L., Van Den Broeck, E., & Van Noort, G. (2018). Like or dislike? Adolescents’ responses to personalised social network site advertising. Journal of Marketing Communications, 24(6), 599–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2016.1182938

WARC. (2023). Global Ad Trends: Social media reaches new peaks https://www.warc.com/content/paywall/article/warc-data/global-ad-trends-social-media-reaches-new-peaks/en-gb/155614

Zarouali, B., Verdoodt, V., Walrave, M., Poels, K., Ponnet, K., & Lievens, E. (2020). Adolescents’ advertising literacy and privacy protection strategies in the context of targeted advertising on social networking sites: implications for regulation. Young Consumers Insight and Ideas for Responsible Marketers, 21(3), 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1108/yc-04-2020-1122

Zhu, Y., & Chang, J. (2016). The key role of relevance in personalised advertisement: Examining its impact on perceptions of privacy invasion, self-awareness, and continuous use intentions. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 442–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.08.048

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. https://cds.cern.ch/record/2655106