index.comunicación | nº 10(1) 2020 |

Páginas 97-123

E-ISSN: 2174-1859 |

ISSN: 2444-3239 | Depósito Legal: M-19965-2015

Recibido el 23_09_2019

| Aceptado el 03_01_2020 | Publicado el 06_04_2020

MALE AND FEMALE

WORKERS. GENDER TREATMENT THROUGH PIXAR'S FILMS

TRABAJADORES Y TRABAJADORAS. EL

TRATAMIENTO DE GÉNERO A TRAVÉS DE LAS PELÍCULAS DE PIXAR

https://doi.org/10.33732/ixc/10/01Malean

Nerea Cuenca-Orellana

Universidad de Burgos

nerea.cuenca.orellana@gmail.com

orcid.org/0000-0003-2888-8403

Patricia López-Heredia

Universidad Autónoma

de Madrid

patricia.lopezh01@gmail.com

orcid.org/0000-0001-6935-2707

![]() Para citar este trabajo: Cuenca-Orellana, N. y López-Heredia, P. (2020). Male and female workers.

Gender treatment through Pixar's films. index.comunicación,

10(1), 97-123. https://doi.org/10.33732/ixc/10/01Malean

Para citar este trabajo: Cuenca-Orellana, N. y López-Heredia, P. (2020). Male and female workers.

Gender treatment through Pixar's films. index.comunicación,

10(1), 97-123. https://doi.org/10.33732/ixc/10/01Malean

Abstract: The concept of 'work'

encompasses knowledge, representations, activities and social relations that

organize and hierarchize society through roles and norms. During more than

fifty years, Disney represented women as the angel from the home and men as

brave and very hard workers. The distribution of tasks has been progressively

modified in our Western society, in animated films as well. In 1989 a new era

started in animation films: Disney changed some characteristics in male and

female characters, but the representation of female workers did not appear

until 2009 with The Princess and the Frog. Tiana is the first worker

princess; she is a waitress that wants to run her own restaurant and she gets

it at the end of the film. But, in 2009, Pixar had released ten films and its

first worker princess was the main character of Bug’s life (John Lasseter,

1998). At first sight, this seems as a very high evolution, but this work wants

to discover how Pixar has represented the world of work: as a way of dividing

characters depending on its gender or as a way of developing and showing

equality to the youngest spectators?

Keywords: characters;

animation; gender; world of work.

Resumen: Dentro del concepto ‘trabajo’ se engloban saberes, repre-sentaciones, actividades y relaciones sociales que organizan y jerarquizan la sociedad mediante roles y normas. Durante más de cincuenta años, se representó a las mujeres como el ángel del hogar y a los hombres como valientes y trabajadores. El reparto de tareas se ha modificado progresivamente en nuestra sociedad occidental, también en el cine de animación. En 1989 comenzó una nueva era en las películas de animación: Disney cambió algunas características en los personajes masculinos y femeninos, pero la representación de personajes en esferas laborales no apareció hasta 2009 con Tiana y el sapo. Tiana es la primera princesa trabajadora, una camarera que quiere dirigir su propio restaurante y lo consigue al final de la película. Pero, en 2009, Pixar había estrenado diez películas y su primera princesa trabajadora fue la protagonista de Bichos (John Lasseter, 1998). A primera vista, esto parece una gran evolución, pero, en este trabajo se busca descubrir cómo Pixar ha representado el mundo laboral: ¿lo ha hecho como una forma de dividir a los personajes según su género o como una forma de desarrollar y mostrar la igualdad a los espectadores más jóvenes?

Palabras clave: personajes; animación; género; mundo laboral.

1. Introduction

For centuries, it was considered that the

differences between masculinity and femininity were determined by nature (Veissière, 2018: 6). However, since the second wave of the

feminist movement took place in the United States in the sixties, researchers

concluded that the roles each gender carries out are determined by the gender

social system (Bogino, 2017: 163). This system, from

the beginning of Western civilization, had allotted women the domestic level

because of their reproductive capacity, while men were in charge of hunting,

ploughing and other physical tasks from the external field thanks to their

physical strength (Medina et al., 2014; Saldívar

et al., 2015). During the Industrialization (1750-1870), the external

field was understood to be indispensable for survival. This gave masculinity a

higher status compared to women (Wharton, 2012: 99). Thus, the role of women in

society was underrated (Ribas, 2004: 3). What started

as a separation set up for coexistence became a fixed ideal that distinguished,

prioritized and opposed human beings according to their gender (Sartelli, 2018: 200-201).

With the beginning of the Second World War

(1939-1945), married women that belonged to a middle class became responsible

for their household economy while their husbands fought on the frontline

(Coronado, 2013). When the conflict

ended in 1945, they stopped working outside their homes (Brioso,

2011: 341). Sometime later, in the fifties, American women managed to have

access to university education, although this opportunity was mostly offered as

a possibility to be at the same cultural level as their future husbands (Del

Valle, 2002: 99), because women had little to no room in the world of work and

so in the end, they got married and devoted themselves to domestic work (Jódar, 2013).

In

the sixties, Social Sciences analyse the

gender-specific division of labour and validate that

this is the cause of patriarchal domination in western societies (Brioso, 2011: 343). In turn, the women who were part of the

new generations and who were more qualified both academically and

professionally for the outside world, demanded opportunities in different

fields and professional sectors (Ramos, 2003: 268). These advances were

progressively achieved between the seventies and the eighties. They entry of women

into the labour market made their husbands take part

both in the household chores and in childcare. These responsibilities were

added to the traditional role of men as main economic providers of the

household, another responsibility that was shared between men and women (Cánovas, 2017: 6).

2. State of the art

The lack of equality in male and female representation, assigning a lower scale to women when they are compared to men, is still presented in today's audiovisual content for all audiences, although it is an issue that began to be investigated in the 80s (Iadevito, 2014: 226). Nowadays, animation is a very powerful tool and children learn both the masculine and feminine ideals that predominate at a particular moment in history through their favorite characters (Pietraszkiewicz, 2017). Those stories help to perpetuate, eliminate or modify behavior patterns according to the gender assigned to the different characters and to what they do within the narrative (Bustillo, 2013: 6). Currently, “(…) preocupa sobre todo la violencia mediática que recae tanto en la representación de mujeres y hombres, en el tratamiento que se les concede a los personajes masculinos y femeninos, así como el efecto que causa sobre las y los espectadores”[1] (Sánchez-Labella, 2915: 9).

For

more than seventy years (1937-2009), Disney did not depict work as a subplot to

develop relationships and/or as a tool to create conflicts amongst the

different characters (Fonte, 2001: 131). It is true that different male

characters such as the hunter from Snow

White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), the butler from The Aristocats (1970), the explorer John

Smith from Pocahontas (1995), or the

Beast’s servants (Beauty and the Beast,

1991) had jobs and these jobs were important within the story. However, in

these examples, their occupation is just another piece of information about the

characters and there barely is any screen time where these characters are shown

doing their job.

Disney used the traditional feminine roles in their feature films. They chose to keep the more traditional vision of femininity that still prevails in our modern age. Due to this, male perceptions dominated the world view that was used for film adaptations. Thus, in its stories, the studio adhered to the traditional role of women within marriage and the home (Davis, 2006: 102). In addition to this, the studio also made stories to be a “factor de transmisión cultural utilizado principalmente durante la socialización primaria que permite inculcar valores diversos” (Sartelli, 2018: 213).

In

2009, the Princess and the Frog was released,

and Disney’s first working princess emerged (Johnson, 2015). In this film, work has an influence on the

main character’s moods, on her decision-taking and even on her relationships

with the rest of the characters (Aguado &

Martínez, 2015: 56).

By

then, Pixar had already been producing feature films for fourteen years. In

particular, between 1995 and 2015, eleven out of the sixteen films that were

released (66%) address the topic of work and the division of labour as an essential matter in the subplots of their

scripts. Since their second release, A

Bug’s Life (1998), work is part of both the individual and the collective

identity of the characters. Jonathan Decker’s research emphasizes that Pixar is

an example to follow. In Decker’s analysis all the characters appeared between

1995 and 2010 have access to the same conditions and opportunities in the labour market, regardless of their gender (Decker, 2010: 86

& 87). Following Decker’s statement, an analysis is carried out to try to

determine whether that statement is true for the two decades that have been analysed.

3. Methodology

This

research aims to describe and analyze the male and female characters in

Hollywood's commercial animation cinema through the viewing of the sixteen

films made by Pixar Animation Studio since 1995, the year in which they began

production, until 2015.This

current research starts by quantifying the number of characters that are shown

working in the sixteen films released by Pixar between 1995 and 2015. Once

these results were obtained, it has been determined which are the occupations

for men and for women that have been depicted in the representative sample

quantifying again. Finally, we have added a table in which the name of the character,

his/her gender, his/her profession and his/her narrative archetype are

organized in order to define how Pixar presents professions in male heros and/or male/female secondary characters.

Through

the quantitative and qualitative analysis of the characters will allow us to

detect and define the patterns of the masculine and feminine types created by

Pixar and their evolution throughout the study time. Similarly, a comparison

can be made between these and those that appeared in the Disney studio films.

Through the study of differences and similarities in issues such as social

representation, the physical aspect, the values they hold or gender

relations, the aim is to determine to what extent society has changed and what

is the image that is currently projected from the animation movies.

4. Results

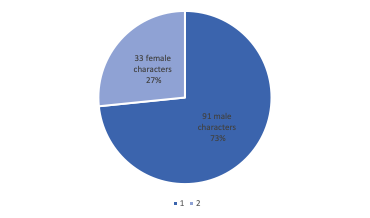

4.1. Quantity results

In

60% of Pixar’s stories, characters seek the same objective: to have

professional success. In Pixar, this accomplishment is linked to maintaining

their jobs, to having social recognition, or to both. In relation to the

quantification of male and female workers, we can appreciate a big difference

as it is represented in the following graph:

Graph 1.

Quantification of male and female characters in the representative sample

(1995-2015)

Source:

own elaboration

After

reviewing the films that were analyzed (Table 1 in Anex),

it can be said that Cars (John

Lasseter, 2006) and Ratatouille (Brad

Bird, 2007) are the two films were there are more working male characters. On

the other hand, A Bug’s Life, Cars and Brave (Mark Andrews and Brenda Chapman, 2012) are the films where

we can find more working female characters: four in each of them. And Monsters University, (Dan Scanlon, 2013)

despite the fact that it is a film with many male characters, it is the most

equitable film out of the sixteen when it comes to work-related issues.

In

fact, in 56.25% of Pixar’s films, the rupture of the everyday routine which the

characters undergo is due to work-related issues. And in 43.75% of the cases,

the beginning of this adventure that the main male characters are responsible

for starts with their jobs. Only in two films there are female characters whose

plots start with their jobs. This entails 12.5% of the feature films. One of

them is Wall-E (Andrew Stanton, 2008), where EVE is in charge of

searching for life on Earth. Her task marks the beginning of the

adventure.

It

is worth stressing that the main objective that the characters from 60% of the

films released by Pixar have, is related to labour

issues. Moreover, in 56.25% of Pixar films, the break in the balance suffered

by the characters in the story is due to a labour

issue. And in 43.75% of the cases, the male protagonists are responsible for

the start of this adventure in order to advance in their job and improve their

status.

The

crisis suffered by the company Monsters Inc. (Pete Docter,

2001) in the film affects Sully beyond his vocation as scary. Unwittingly,

Sullivan is involved in a whole web of corruption and deception. In particular,

Waternoose himself, the owner of the company, has an

agreement with Sully’s rival, Randall, so as to introduce human children in the

factory for the purpose of increasing the energy levels, but also to recover

his power and thus to supply all the city. All Monstropolis

believe that children are toxic. The triggering incident that begins the story

is when Sully discovers a small human girl who is two or three years old in the

factory.

Mike's

dream, at Monsters University, is to

get to the best college of scarers. But although he

studies and works very hard to achieve his dream, he does not have enough

faculties. Thus, the green monster finds that he can be expelled from the

university if he does not pass the exam. This is how Mike sees his dream falter

and with it, his future work.

Laziness

in Bob's work and his subsequent dismissal are the trigger for The Incredibles (Brad Bird, 2004). This

situation coincides with the proposal of a new job position, adjusted to his

profession of superhero. He does not hesitate to accept the successive missions

proposed by Mirage, who is, in reality, the villain Syndrome’s secretary and

partner. In this way he begins his first internal change: with the new job, Bob

is happier, he integrates better in his family, and both his adventure and his

arc of transformation begin.

The

missions for which Eva and Wall-E are programmed are, precisely, their

respective jobs. The trigger to start the adventure in Wall-E arises when Wall-E decides to leave his job and his planet

to take care of Eva, who has been picked up by a ship after entering a state of

hibernation. This fact is relevant from the narrative point of view: the hero

leaves his habitat and moves to his beloved leaving all his world behind. The

beginning of the adventure coincides with what it was the ‘happy ending’ of

Disney films starred by princesses. But, in this case, it is the male character

who leaves everything to start a new life with his beloved Eva.

The

breaking of the balance in the work environment also occurs in Cars, Lightning McQueen is used to

competing and he feels he is the best on the track. McQueen cannot win the

Piston Cup in the first race and travels to a new destination to get it. On the

way he gets lost and does not reach the new competition. During his time in

Radiator Springs, he discovers and learns values such as respect and

friendship and to enjoy small moments. When he returns to work, McQueen has a new

personality, with new values and real friendships.

In

Cars 2 and Ratatouille the protagonists are involved in a work-related lie:

Mate, as a spy and Lingüini, as a cook. Lingüini

maintains the wrong idea that Gusteau's workers have

made of him during a half of the film, while

Mate barely realizes that he is working for some spies and that his

contribution is very valuable. Both

mistakes lead to the development of professions for which they do not seem to

have the necessary skills. However, both Lingüini and

Mate begin a journey in which they discover that they can be very happy

exploiting their abilities and using themselves.

Only

in two films there are female Pixar characters whose plot begins with work.

This means 12.5% of the films. One of them is Wall-E, where Eva is responsible

for looking for life on the planet Earth. Her mission is the trigger for the

adventure to begin.

Atta’s

future job in A Bug’s Life is the

trigger to evolve and this leads to an adventure. Atta has to manage the ant colony,

still with the help of her mother. Atta feels stressed and does not know how to

face her new position. As soon as

she starts exercising, even though

all the ants are perfectly organized, Flik throws the

food collected for months for the grasshoppers into the river. This is the

beginning of an adventure for her to collect food again, which implies a greater organization and supervision of the

members of the colony that this demands.

In

18.75% of the films, the responsibility in the work and narrative objective of

their male partners directly affects female characters such as Helen, Colette

and Riley. Helen abandons her housework and motherhood, her profession until

she decides to go in search of Bob. Colette's adventure begins when she meets Lingüini. She is already a professional and Chef Skinner

asks her to show him how Gusteau's kitchen works.

After putting her trust in Lingüini, Colette loses

her to discover that she has lied to him and decides to leave but realizes that

Chef Gusteau's dream has come true: anyone can cook.

In

Inside Out, Riley's father accepts a

new position in San Francisco, and that's why the whole family move to the new

city. His father’s new job is the trigger that breaks the balance of the

eleven-year-old girl. She is happy in her school, in her hockey team, with her

friends and playing with her parents. However, in her new home her parents do

not have so much time to spend with her, she does not have friends, she is not

selected by another hockey team and she does not adapt to the new school.

In

46.6% of the films, work is an element that provokes the arc of transformation

of, at least, one of the characters. For example, the internal evolution of

Helen in The Incredibles means that

from the middle of the film until the end she takes care of her family, of

combating evil and of supervising her image.

And with work there is also the fear of not

measuring up, of doing it badly, although this fear is expressed unequally in

male and female characters. Atta, Shiftwell and Helen

have at some point a feeling that is not seen in the performance of the

professions of male characters, except in Lingüini

and this is because the boy is lying about

his capabilities. 18.75% of the

films have female characters who suffer crisis in their jobs that are due to

the lack of security in themselves to show their ability as professionals and

solve the contingencies that arise. On the other hand, male characters do not

suffer professional crisis in the same way as female characters, they are

confident in the performance of their tasks and know their abilities, as well

as how to use them to achieve professional success.

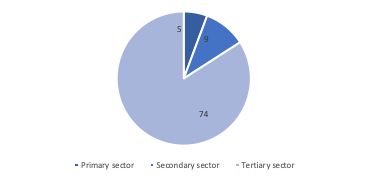

Graph 2. Labour sectors. Pixar’s male characters (1995-2015)

Source:

own elaboration

The

vast majority of working male characters (74 out of 91 characters) are

dedicated to professions included in the tertiary sector (services), but there

are also 9 characters whose work activity belongs to the secondary (industrial)

sector and 5 male workers in the primary sector (agriculture).

Graph 3. Labour sectors. Pixar’s female characters (1995-2015)

Source:

own elaboration

In

33.3% of the Pixar filmography, female characters appear in jobs that, before

the 80s, were conceived as typical of the male gender. Out of 125 worker

characters, only 29 are women: almost all (25) work in the tertiary sector.

The

vast majority of working male characters (74 of 91 characters) are dedicated to

professions included in the tertiary sector (services), but there are also 3

characters whose work activity is included in the secondary (industrial) sector

and 5 male workers, in the primary sector (agriculture).

In

any case, the social changes of the last fifty years have allowed women to

enter the world of work outside the home. And this moved to the cinema from the

90s. Although 81.25% of female characters occupy positions with little

decision-making capacity or in traditionally feminine areas (education, care

for others, sewing, cleaning, cooking), Pixar has also created female

characters that break the work box. Female characters begin to occupy high

positions: 18.75% of the films include female characters who lead a company or

even a community.

With

all this information we can summarise that,

quantitatively, Pixar underrepresent female characters when it comes to the

employment sphere. But, beyond this quantification, we will continue our

analysis by describing what the jobs are for each gender to find that there

also is underrepresentation in the job positions. In order to do this, and

before describing the professions of each character (and their narrative

archetype in the story) we have included a table in Anex

(Table 4. Characters, gender and professions in the representative sample. Compilation).

4.2. Quality results

4.2.1. Male jobs in Pixar’s films

In

Pixar, the division of labour outside the home has

been influenced by the Western gender division (Medialdea,

2016: 90). Pixar represent the traditional system of task division which has

always been associated to the family as an institution, and its influence on

the gender-specific division of labour can be seen in

The Incredibles and in Brave (Martínez, 2017: 354). Bob (The Incredibles, 2005) and Fergus (Brave, 2012) are the husbands within a

traditional family which starts by getting married to their wives and then

having children, in that order (Gálvez, 2009: 11).

The two of them represent the ‘breadwinner’

(Wharton, 2012: 104). Their wives, Helen and Elinor, respectively, do not

work outside their homes. Helen does leave to rescue her husband as a

superheroine, but she does so because of her duty as a housewife that cares for

her family, and as someone that wants to keep all of them together, not as part

of her professional development. As for Elinor, she is the queen and she is to

raise her daughter Merida so that she is ready to inherit her role. Elinor

always does so inside the castle as part of her maternity. It is also worth

mentioning here that for Bob, his job is an essential aspect of his own

individual/personal development. Bob’s own apathy when it comes to his job and

his subsequent dismissal are part of the trigger in The Incredibles. This situation happens at the same time as Bob

gets an offer for a new job position which matches his job as a superhero. He

does not hesitate to accept the following missions that are proposed by Mirage,

who in reality is the villain Syndrome’s secretary and partner. His first

internal changes start like this: with his new job, Bob is happier, his relationship

with his family improves, and both his adventure and his transformation start.

In

Pixar, the jobs that the male characters have are quite varied: chef, sheriff,

space ranger, athlete, chief detective, firefighter, soldier, entrepreneur,

administration chief or judge, amongst others[2]. Sulley and Mike from Monsters,

Inc. work in the Monsters, Inc. Company scaring children. Both of them are

happy and they are successful thanks to their hard work and their daily

efforts. This situation can also be seen at Gusteau’s

restaurant in Ratatouille, where all

the workers are male except for Colette. Haute cuisine has always been

considered a male domain and Ratatouille

still represents this work environment in this way (Del Valle, 2002: 96).

Within

Pixar’s masculinity, there is a complex hierarchical system where preference is

given to those males that fulfil the established social norm: the workers that

are successful are those who are tolerant, modest, who know to work in teams

and whose sense of team spirit has been developed, giving preference to the labour necessities that others have, even over their own.

This can be seen in Remy, from Ratatouille,

and this is what McQueen, from Cars,

and Bob, from The Incredibles, learn.

Teaching

and cleaning are two jobs that are barely relevant to male characters within

Pixar, but they do appear respectively in Finding

Nemo and Toy Story 3. Cleaning

has been a task traditionally assigned to women as part of the household

chores, and something that they could continue doing outside it (Goñi, 2002). The figure of the teacher has always been a

clear reference to authority and power in the western society (Del Valle, 2002:

117). Showing a male preschool teacher in one of their first films reinforces

Pixar’s search of progress towards gender equality. Different sectors such as

education and the health service have always been associated to the female

gender (Medialdea, 2016: 93).

4.2.2. The inclusion of Pixar’s female

characters in the world of work

Social

changes like divorce or women’s access to university allowed women to enter the

labour market outside the home, regardless of their

marital status (Gálvez, 2009: 15). These changes were

reflected in animation films during the nineties[3].

81.25% of the Pixar’s female characters analysed hold

positions with little decision-making capacities, or in areas that have always

been traditionally associated with women: education, caring for others,

dressmaking, cleaning, or cooking. Pixar have also created female characters

that break the stereotypes related to the inability to climb the professional

ladder, but this does not happen very often.

In 33.3% of Pixar’s films, there are female characters

that hold job positions that, before the eighties, were traditionally

associated with men. Only three female characters hold the position with the

highest responsibility within the companies where they work, thus copying the

western social model that prevailed at the moment of filmings

(Gómez, 2018: 178). These characters are Roz (Monsters, Inc., 2001), dean Hardscrabble (Monsters University, 2013) and Atta from A Bug’s Life (1998). According to Eisenhauer, we have been

socially educated to understand that both power and authority are male

characteristics, while femininity is characterised by

the lack of power (Eisenhauer, 2017: 14-15). Focusing on Roz and Hardscrabble,

both have a masculine aspect, an idea that makes reference to independent,

strong, active, determined and self-confident women (Del Valle, 2002: 167-168).

Roz (Monsters, Inc., 2001) is an

undercover agent. Dean Hardscrabble, in Monsters

University, faces the responsibility of leading an entire university campus

after being promoted since she started as a student. In both films we can see

two female characters that are presented as modern women, that “(…) se han atrevido a transgredir los roles y estereotipos

de género prescritos tradicionalmente”[4]

(Ramos, 2003: 268).

Roz

and Hardscrabble have something in common: their professional activity is

linked to a personality where they stand firm in their convictions and strict

in their way of acting. This is the idea of leadership in the real world

(Martínez Ayuso, 2015: 50). Montesinos (2002: 49)

considers that these are two characteristics that appear in women when they

have to lead because it was job position that in previous decades was

traditionally male, and they take that as reference.

Roz

and Hardscrabble establish cold and distant relationships with the rest of the

characters. This can be compared with the image of the woman that abuses her

power and which has been reflected in Disney’s witches and female villains

until 2016 (Streiff & Dundes,

2017: 9). In fact, throughout the film, we do not know anything about the

private lives of these two characters. We only know them through their job

interests. The lack of social relationships, or their non-appearance (in

particular, family and love relationships) may have to do with this full

dedication to their jobs, because this is how it happens in the real world (Medialdea, 2016: 96). These characteristics have nothing to

do with the traditional view of femininity in which women were understood to be

sensitive and close to others, which facilitated their relationships with

others (Lamo de Espinosa, 2000: 82). Roz and dean

Hardscrabble are proof that, nowadays, any woman can lead a university campus

or be part of the judicial field, which has traditionally been led by men.

However, the strict way in which they do their jobs and teach the characters is

rejected by the audience, at least at first. Both Roz and dean Hardscrabble

represent the idea of femininity and leadership that was proposed by Colón,

Plaza and Vargas (2013: 68): “(…) las mujeres que transgreden el mandato social se estigmatizan todavía como poco respetables

y confiables, mala mujer y madre”[5].

At the end of the films, it is confirmed that the strict attitude the two of

them had, was based on everybody’s protection and well-being when fulfilling

the established rules, and that shows a more positive image.

Atta

in A Bug’s Life (1998) inherits the

leader position in the ant colony from her mother, so she rules as queen. It is

important to emphasise that she has this power

because she inherits it, not because she has earned it or because she has

proven that she can be the colony leader. In the real world, family businesses

are usually inherited by men (Gatrell, 2008: 12).

This is an important change: Princess Atta actively participates in the public

life and she progresses socially without the need of a husband or another male

to attain her position. Let us remember that Disney did not include a leader

princess exercising her responsibilities without a spouse until Elsa in Frozen (2013) (Johnson, 2015: 24). Del

Valle believes that female leadership is different from that of males.

Regarding the former, she states that women are more concerned about doing

things right, while men tend to be more individualistic (Del Valle, 2002: 195-200).

It is also worth mentioning that Atta’s future job is the trigger needed to

evolve and this results in an adventure. Atta has to manage the ant colony,

although she still has her mother’s help.

Despite all that has been mentioned before, in Pixar

there is a predominance of women whose jobs indicate there are inequalities

between men and women. In this regard, Pixar’s films strengthen Haywood’s idea

that says that the distribution of job positions has not changed (Haywood,

2003: 25). In this sense, Pixar adjust to the pace that the society which the

films are directed to, have. The jobs that women have held, even after their

access to the university sector and the world of work, are linked to their

service to others: health, education, household chores, restaurants and hotels

(González, 2004: 6-9).

Colette,

in Ratatouille, and Edna from The Incredibles, have a lot to do with

this. The former is the only female cook at Gusteau’s

and she tells Lingüini the efforts she has made in

order to work there. Edna is a dressmaker, and sewing was linked to household

chores until the middle of the 20th century, and therefore, to

women.

In

Pixar there are also female secretaries, waitresses, female teachers, flight

attendants or receptionists. Pixar represent these occupations through female

characters in 20% of the films. Out of all of them, only the job as a teacher

is portrayed by a male character. It is exactly within that care for others

where the teacher’s job lies. It is thought that the job as primary teachers is

mainly carried out by women because “(…) la sociedad supone que las mujeres son cooperativas, comprensivas, amables y apoyan a los demás”[6]

(Ramos, 2003: 273). Every single teacher we see at Sunnyside (the Toy Story 3 nursery) are women, just

like Mike Wazowski’s teacher in primary school, which

can be seen at the beginning of Monsters

University, is also a woman. The performance of this work with little

children is connected to the traditional idea that states that women are

equipped with an emotional development that makes it easier for them to look

after and meet the needs of babies and children until primary school much

better than any man would (Pascual, 2014). There are other female characters in

professional fields that have traditionally been associated with women, such as

Barbie, in Toy Story 2, and Gypsy,

from A Bug’s Life. Both of them are

flight attendants and they share the importance that their physical aspects

have in order to do their jobs and their ability to serve others.

5. Conclusions

To start with, it is important to take into account that this research has the limitations of an experimental design based on a limited number of observations, but, we have to bear in mind that the results are relevant to have a much better knowledge of how male and female representations are built in animation films. As it is known, we cannot forget that “el hecho de que los dibujos animados contengan gran cantidad de referencias de la vida real hace que los consumidores a veces entiendan las historias y las acciones como verosímiles”[7] (Sánchez-Labella, 2015: 10).

While

Disney proposed the first working male character in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and the first working

princess in 2009 with Tiana and the frog,

Pixar already present work as a main field. In it, male and female characters

develop their capacities and success since its second premiere: A Bug’s Life (1998). Therefore, in

Pixar, the male and female role at

work is, without a doubt, the relationship that has developed the most in Pixar if we compare it with Disney.

In

Pixar’s labour world, like in the western real world,

power is embodied by men (Meza, 2018: 11). In this way, Pixar follow the idea

of presenting working female characters. However, only a minority of them hold

high positions. Following the system that still remains in the current western

world, jobs are still highly sexualized (Hidalgo Marí,

2017: 310-311), as films analyses showed us. This also happens in the real

world, in particular in positions such as receptionists, secretaries or

waitresses (Gatrell, 2008: 42).

After

this analysis, we can also prove that helping, services and caring for others

are qualities which are still associated with the female identity (Jenaro, 2014: 51). Regarding male characters, Pixar still

present male success as part of having a good job which makes them grow. Working on developing masculinity and femininity in equality, Pixar have only needed twenty years to increase and improve their gender

representation.

The

female characters of Pixar are professionals able to work in any field and

demonstrate with their skills that they are 'competent professionals' in their

area, although the services sector is still the one that covers the vast

majority of female characters in the 20 years analysed:

they work there 81.25% of the times. Revising this information and comparing

with the western world nowadays:

The EU’s aim is to reach a 75 % employment rate for men and women by 2025. In 2017, female employment continued to increase slowly but steadily, similarly to that of men, and reached 66.6% in the third quarter of 2017. Despite this progress, women are still a long way off achieving full economic independence. In comparison to men, women still tend to be employed less, are employed in lower-paid sectors, work on average 6 hours longer per week than men in total (paid and unpaid) but have fewer paid hours, take more career breaks and face fewer and slower promotions (European Union, 2018: 9).

In

fact, Pixar’s female characters suffer a vertical segregation in access to jobs

with power. Therefore, despite the evolution shown by the characters under the

icon 'superwoman', they continue to work, mostly, in positions traditionally

assigned to the female gender, as also happens with male characters, where

there is only one teacher, one waiter and one cleaner out of the total 16

films:

No obstante, la

igualdad no se ha conseguido, pese a que sea indiscutible que se ha producido

un cambio en los modelos de feminidad y masculinidad actuales respecto al siglo

XX. Los datos económicos y

laborales más actuales muestran que los antiguos roles de género todavía no han

sido desterrados del mundo del trabajo (…)[8] (Martínez, 2017: 135).

Pixar’s

male characters live devoted to their work and that is the reason for the

beginning of the adventure (or it is related to it) in just over half of the

films (56.25%). Therefore, this masculine behavior (valuing work above or at

the same level as other relationships) is presented as something natural.

Mass

media are a very powerful tool to present different options regarding

masculinity and femininity that can guide us towards equality and a stage of

normalization (Johannah, 2018). In addition to this,

it is essential to point out how necessary it is to design characters that

attract children but that encourage them as well, in order to choose their

future work life because of their abilities and interests and not because of

their gender. In addition to this, it is needed to point out how necessary is

to design characters that attract children but that encourage them as well, in

order to choose their future labour life because of

their abilities and interests and not because of their gender.

Bibliography

Aguado, D. y Martínez, P. (2015). ¿Se ha vuelto Disney feminista? Un

nuevo modelo de princesas empoderadas. Área

Abierta, 15 (2), 49-61.

Consultado el 11 de enero de 2019: https://www.academia.edu/13694941/_Se_ha_vuelto_Disney_feminista_Un_nuevo_modelo_de_princesas_empoderadas?auto=download

Unión Europea (2018). 2018 Report on equality between women and

men in the UE. Luxemburgo: OIB.

Martínez, M. (2017).

Desmontando clichés o la evolución de los modelos

de feminidad y masculinidad en los escenarios. En García-Ferrón, E.

y Ros-Berenguer C. (coords.), Dramaturgia femenina actual.

De 1986 a 2016. Feminismo/s (30),

129 -145.

Bogino, M. y Fernández-Resines P. (2017). Relecturas

de género: concepto normativo y categoría crítica. La ventana (45), 158-185.

Brioso, A.B. (2011). Perspectivas de género como pieza

fundamental en trabajo social. Consultado el 15 de abril de 2018: https://docplayer.es/5268781-Perspectivas-de-genero-como-pieza-fundamental-en-trabajo-social.html

Bustillo, M. (2013). Conocimientos y valores en el cine. Una

propuesta para 6º de primaria. (TFG). Facultad de Educación de la UNIR. La

Rioja. Consultado el 16 de enero de 2019: https://reunir.unir.net/handle/123456789/1865

Cánovas Marmo, C. (2017). Las mujeres, el laberinto cultural y

la asunción del pensamiento crítico. Management

Review, 2 (2).

Consultado el 10 de diciembre 2018: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6054221

Colon, A., Plaza, A., & Vargas, L.

(2013). Construcción socio-cultural de la feminidad. Informes Psicológcios

13 (1), 65-90.

Coronado, C. (2013).

Mujeres en guerra: la imagen de la mujer italiana en los noticiarios Luce

durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial (1940-1945). Revista de Estudios de Género. La ventana, 177-208. Consultado el

23 de octubre del 2018: http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/laven/v4n37/v4n37a8.pdf

Davis, A.M. (2006). Good Girls and Wicked Witches. Women in Disney's Feature Animation. Bloomington, Estados Unidos: Indiana University Press.

Decker, J., (2010). The Portrayal of

Gender in the Feature-Length Films of Pixar Animation Studios: A Content

Analysis. (Thesis).

Auburn University, Alabama. Consultado el 12 de

febrero de 2014: https://etd.auburn.edu/handle/10415/2100

Del Valle, T.A. (2002). Modelos emergentes en los sistemas y las relaciones de género. Madrid, España: Narcea S.A.

Eisenhauer, K. (2017). Gendered

compliment behavior in Disney and Pixar: A Quantitative Analysis. Consultado el 22 de diciembre de 2018: www.kareneisenhauer.org/wp.../Eisenhauer-Capstone-Excerpt.pdf

Fonte, J. (2001). Walt Disney. El universo

animado de los largometrajes 1970-2001. Madrid: T & B Editores,

Gálvez, R. (2009). Comunicación, género y prevención de

violencia. Manual para comunicadores y comunicadoras. Fondo de Población de

Naciones Unidas (UNFRA). Consultado el 25 de enero de 2015: americalatinagenera.org/newsite/images/sistematizacion_exp_diplomado_honduras.pdf

Gatrell, C.S. (2008). Gender and Diversity in Management. A Concise Introduction. Londres, Inglaterra: SAGE.

Gómez, M. (2018). Jornadas

nacionales: el acceso de las mujeres al deporte profesional: el caso del

fútbol. Seminario Mujer y Deporte.

Madrid: Femeris. doi.org/10.20318/femeris.2018.4325

González, S.M. (2004).

Igualdad de oportunidades entre mujeres y hombres en el mercado laboral. Encuentro de empresarias de la Macaronesia, Universidad Las Palmas de Gran Canaria,

1-25.

Goñi, C. (2008). Lo femenino. Género y

diferencia. Pamplona: EUNSA.

Haywood, C.Y. (2003). Men and Masculinities: Theory, research and social practice. Buckingham, Inglaterra:

Open University Press.

Hidalgo, T. (2017). De la

maternidad al empoderamiento: una panorámica sobre la representación de la

mujer en la ficción española. Prisma

Social (2), 291-314.

Iadevito, P. (2014). Teorías de género y cine. Un aporte a

los estudios de la representación. Universitas

Humanística 78, 211-237. doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.UH78.tgcu.

Jenaro, C.F. (2014).

Actitudes hacia la diversidad: el papel del género y de la formación. Cuestiones de género: de la igualdad y la

diferencia (9), 20-62.

Jódar, C. (2013). Arquitectura y vida americana de los '50. Recuperado de Amanece Metrópolis: Consultado el 23 de

octubre del 2018: http://amanecemetropolis.net/the-good-wife-arquitectura-y-vida-americana-de-los-50/

Johannah, L. (2018). Women's

Voice in humanitarian media. No surprises. Consultado el 19 de diciembre de 2018: https://humanitarianadvisorygroup.org/wp-content/uploads/

2018/03/HAG-Womens-Voice-in-Humanitarian-Media.pdf

Johnson, R.M., (2015). The Evolution of Disney Princesses and their Effect

on Body Image, Gender Roles, and the Portrayal of Love. Educational Specialist. 6. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/edspec201019/6

Lamo de Espinosa, E.

(2000). La feminización de la reproducción: ambivalencia, desasosiego y

paradojas. En Durán, M. Á. Nuevos

objetivos de igualdad en el siglo XXI. Las relaciones entre mujeres y hombres

(75-98). Madrid, España: Publicaciones DGM.

Martínez, V. (2015). Causas del techo de cristal: un estudio

aplicado a las empresas del IBEX35. (Tesis) Facultad de Ciencias Económicas

y Empresariales. UNED.

Martínez, J.A. (2017).

Estereotipo, prejuicio y discriminación hacia las mujeres. Cuestiones de género: de la igualdad y la diferencia (12), 347-364.

Medialdea, B. (2016). Discriminación laboral y trabajo de

cuidados: el derecho de las mujeres jóvenes a no decidir. ATLÁNTICAS – Revista Internacional de Estudios Feministas 1 (1),

90-107. doi.org/10.17979/arief.2016.1.1.1792

Medina, P., Figueras, M. y Gómez, L.

(2014): El ideal de madre en el siglo XXI. La representación de la maternidad

en las revistas de familia. Estudios

sobre el Mensaje Periodístico 20, (1), 487-504. Madrid, Servicio de

Publicaciones de la Universidad Complutense.

Meza, C.A. (2018).

Discriminación laboral por género: una mirada desde el efecto techo de cristal.

Equidad y Desarrollo (32), 11-31. Consultado

el 28 de diciembre de 2018: https://ideas.repec.org/a/col/000452/016465.html

Montesinos, R. (2002). Las rutas de la masculinidad. Ensayos sobre

el cambio cultural y el mundo moderno. Barcelona, España: Biblioteca

Iberoamericana de Pensamiento. Gedisa.

Pascual, G. (2014). La educación infantil, ¿un trabajo de

mujeres? (TFG) Universidad de La Rioja. Consultado el 23 de octubre del

2018: https://biblioteca.unirioja.es/tfe_e/TFE000701.pdf

Pietraszkiewicz, A. (2017).

Masculinity Ideology and Subjective Well-Being in a Sample of Polish Men and

Women. Polish Psychological

Bulletin 48 (1), 79-86.

Ramos, A.B. (2003).

Mujeres directivas, espacio de poder y relaciones de género. Anuario de Psicología, 267-278.

Ribas Bonet, M.A. (2004).

Desigualdades de género en el mercado laboral: un problema actual.

Saldívar, A., Díaz, R., Reyes, N. E., Armenta, C., López, F., Moreno, M., Romero, A., Hernández, J., Domínguez,

M. (2015). Roles de Género y Diversidad: Validación de una Escala en Varios

Contextos Culturales. Acta de

Investigación Psicológica - Psychological Research Records. Consultado el 17 de octubre de 2081: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=358943649003

Sánchez-Labella, I. (2015) Veo

Veo, qué ven. Uso y abuso de los dibujos animados.

Pautas para un consumo responsable. Madrid, Inquietarte.

Saneleuterio, E. y López-García-Torres,

R. (2018). Algunos personajes Disney en la formación infantil y juvenil: otro

reparto de roles entre sexos es posible. Cuestiones

de género: de la igualdad y la diferencia (13), 209-224.

Sartelli, S.L. (2018). Los roles de género en cuentos

infantiles: perspectivas no tradicionales. Derecho

y Ciencias Sociales (18), 199-218.

Streiff, M. y Dundes,

L. (2017). From Shapeshifter

to Lava Monster: Gender Stereotypes in Disney’s Moana. Social Science 6 (91).

Consultado el 18 de diciembre de 2018: www.mdpi.com/journal/socsci

Veissière, S.P.L. (2018). Toxic Masculinity in the age of #MeToo: ritual, morality and gender archetypes across cultures, Society and Business Review.

Wharton, A.S. (2012). The Sociology of Gender. An Introduction to Theory and Research. Oxford, Inglaterra: Wiley-Blackwell.

Anex

Table 1. Quantification of characters in the representative sample. Compilation

|

Film |

Total number of male characters (workers) |

Total number of female characters (workers) |

Total number |

|

Toy Story (1995) |

3 |

0 |

3 |

|

A Bug’s Life (1998) |

8 |

4 |

12 |

|

Toy Story 2 (1999) |

4 |

3 |

7 |

|

Monsters, Inc. (2001) |

6 |

2 |

8 |

|

Finding Nemo (2003) |

2 |

1 |

3 |

|

The Incredibles (2005) |

6 |

3 |

9 |

|

Cars (2006) |

15 |

4 |

19 |

|

Ratatouille (2007) |

12 |

1 |

13 |

|

Wall-E (2008) |

4 |

1 |

5 |

|

Up (2009) |

8 |

1 |

9 |

|

Toy Story 3 (2010) |

5 |

3 |

8 |

|

Cars 2 (2011) |

7 |

1 |

8 |

|

Brave (2012) |

4 |

4 |

8 |

|

Monsters University (2013) |

3 |

3 |

6 |

|

Inside Out (2015) |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

The Good Dinosaur (2015) |

3 |

2 |

5 |

|

Total |

91 |

33 |

125 |

Source:

own elaboration

Table 2. Labour sectors male characters.

Compilation

|

Film |

Primary sector (agriculture) |

Secondary sector (industry) |

Tertiary sector (services) |

|

Toy Story (1995) |

|

|

3 |

|

A Bug’s Life (1998) |

1 |

|

7 |

|

Toy Story 2 (1999) |

1 |

|

3 |

|

Monsters, Inc. (2001) |

|

6 |

|

|

Finding Nemo (2003) |

|

|

2 |

|

The Incredibles (2005) |

|

|

6 |

|

Cars (2006) |

|

|

15 |

|

Ratatouille (2007) |

|

|

11 |

|

Wall-E (2008) |

|

2 |

2 |

|

Up (2009) |

|

1 |

8 |

|

Toy Story 3 (2010) |

|

|

4 |

|

Cars 2 (2011) |

|

|

7 |

|

Brave (2012) |

|

|

4 |

|

Monsters University (2013) |

|

|

1 |

|

Inside Out (2015) |

|

|

1 |

|

The Good Dinosaur (2015) |

3 |

|

|

Source:

own elaboration

Table 3. Labor sectors female characters. Compilation

|

Film |

Primary sector (agriculture) |

Secondary sector (industry) |

Tertiary sector (services) |

|

Toy Story (1995) |

|

|

|

|

A Bug’s Life (1998) |

|

|

4 |

|

Toy Story 2 (1999) |

1 |

|

1 |

|

Monsters, Inc. (2001) |

|

1 |

1 |

|

Finding Nemo (2003) |

|

|

1 |

|

The Incredibles (2005) |

|

|

3 |

|

Cars (2006) |

|

|

4 |

|

Ratatouille (2007) |

|

|

1 |

|

Wall-E (2008) |

|

|

1 |

|

Up (2009) |

|

|

1 |

|

Toy Story 3 (2010) |

|

|

1 |

|

Cars 2 (2011) |

|

|

1 |

|

Brave (2012) |

|

|

4 |

|

Monsters University (2013) |

|

|

2 |

|

Inside Out (2015) |

|

|

|

|

The Good Dinosaur (2015) |

2 |

|

|

Source:

own elaboration

Table 4.

Characters, gender and professions in the representative sample. Compilation

|

Film |

Character’s name |

Gender |

Profession |

Archetype |

|

Toy Story |

Woody |

Male |

Sheriff |

Hero |

|

Toy Story |

Buzz |

Male |

Astronaut |

Hero |

|

Toy Story |

Andy’s mother |

Female |

Mother |

Hero’s mother |

|

Toy Story |

Pizza Planet’s delivery man |

Male |

Pizza Planet’s delivery man |

Secondary character |

|

A Bug’s life |

Atta |

Female |

Princess |

Helper |

|

A Bug’s life |

Atta’s mother |

Female |

Queen |

Trickster |

|

A Bug’s life |

Flick |

Male |

Inventor and colector |

Hero |

|

A Bug’s life |

P.T. |

Male |

Circus’ owner |

Trickster |

|

A Bug’s life |

Gipsy |

Female |

Event hostess |

Trickster/Helper |

|

A Bug’s life |

Manny |

Male |

Fortune teller |

Trickster/Helper |

|

A Bug’s life |

Francis |

Male |

Juggler |

Trickster/Helper |

|

A Bug’s life |

Slim |

Male |

Juggler |

Trickster/Helper |

|

A Bug’s life |

Rosie |

Female |

Tamer |

Trickster/Helper |

|

A Bug’s life |

Dim |

Male |

Circus’ beast |

Trickster/Helper |

|

A Bug’s life |

Truck y Roll |

Male |

Comedians |

Trickster/Helper |

|

Toy Story 2 |

Woody |

Male |

Sheriff |

Hero |

|

Toy Story 2 |

Buzz |

Male |

Astronaut |

Hero |

|

Toy Story 2 |

Madre de Andy |

Female |

Mother |

Hero’s mother |

|

Toy Story 2 |

Pete |

Male |

Foreman |

Shadow |

|

Toy Story 2 |

Jessy |

Female |

Cowgirl |

Helper |

|

Toy Story 2 |

Barbie |

Female |

Stewardess |

Trickster |

|

Toy Story 2 |

Al |

Male |

Toy Shop’s owner |

Threshold Guardian |

|

Monsters Inc. |

Sully |

Male |

Scarer (Factory’s operator) |

Hero |

|

Monsters Inc. |

Mike |

Male |

Scarer’s helper (Factory’s operator) |

Hero/helper |

|

Monsters Inc. |

Sr. Waternoose |

Male |

Factory’s owner |

Shadow |

|

Monsters Inc. |

Randall |

Male |

Scarer (formerly) |

Threshold guardian |

|

Monsters Inc. |

Fungus |

Male |

Scarer’s helper (Factory’s operator) |

Threshold guardian’s helper |

|

Monsters Inc. |

Roz |

Female |

Secretary/CDA Boss |

Shapeshifter |

|

Monsters Inc. |

Celia |

Female |

Recepcionist |

Trickster/Helper |

|

Monsters Inc. |

CDA workers |

Male |

CDA workers |

Secondary character |

|

Finding Nemo |

Marlin |

Male |

Father |

Hero |

|

Finding Nemo |

Nemo |

Male |

Student |

Hero |

|

Finding Nemo |

Mr. Ray |

Male |

Teacher |

Trickster |

|

Finding Nemo |

Dr. Philippe Sherman |

Male |

Dentist |

Threshold guardian |

|

Finding Nemo |

Barbara |

Female |

Recepcionist/secretary |

Secondary character |

|

The Incredibles |

Bob |

Male |

Insurance seller, superhero |

Hero |

|

The Incredibles |

Gilbert |

Male |

Bob’s boss |

Threshold guardian |

|

The Incredibles |

Helen |

Female |

Housewife/superheroine |

Helper |

|

The Incredibles |

Edna |

Female |

Dressmaker and designer |

Herald |

|

The Incredibles |

Director colegio |

Male |

School principal |

Secondary character |

|

The Incredibles |

Dash’s teacher |

Male |

Teacher |

Secondary character |

|

The Incredibles |

Syndrome |

Male |

Inventor |

Shadow |

|

The Incredibles |

Mirage |

Male |

Secretary |

Shapeshifter |

|

The Incredibles |

Frozone |

Male |

Superhero |

Helper |

|

Cars |

Rayo |

Male |

Race runner |

Hero |

|

Cars |

Mate |

Male |

Crane |

Helper |

|

Cars |

Chik Hicks |

Male |

Race runner |

Threshold guardian |

|

Cars |

El Rey |

Male |

Race runner |

Secondary character |

|

Cars |

Sally |

Female |

Lawyer and hotel’s owner |

Herald |

|

Cars |

Flo |

Female |

Waitress |

Trickster |

|

Cars |

Ramón |

Male |

Workshop’s owner |

Trickster |

|

Cars |

Doc Hudson |

Male |

Jude

and ex- race runner |

Mentor |

|

Cars |

Mia |

Female |

Cheelader |

Trickster |

|

Cars |

Tia |

Female |

Cheelader |

Trickster |

|

Cars |

Luiggi |

Male |

Mechanic |

Trickster |

|

Cars |

Sheriff |

Male |

Sheriff |

Trickster |

|

Cars |

Mack |

Male |

Driver |

Trickster |

|

Cars |

Broadcaster (2) |

Male |

Broadcaster |

Secondary character |

|

Cars |

Manager |

Male |

Manager |

Secondary character |

|

Cars |

Guido |

Male |

Mechanic |

Trickster |

|

Cars |

Rojo |

Male |

Firefighter |

Trickster |

|

Cars |

Fillmore |

Male |

Militay |

Trickster |

|

Ratatouille |

Lingüini |

Male |

Cooker |

Hero |

|

Ratatouille |

Remy |

Male |

Cooker |

Hero |

|

Ratatouille |

Colette |

Female |

Cooker |

Helper |

|

Ratatouille |

Chef Skinner |

Male |

Chef |

Shadow |

|

Ratatouille |

Ego |

Male |

Culinary critic |

Threshold guardian/Shapes. |

|

Ratatouille |

Gusteau |

Male |

Chef |

Herald |

|

Ratatouille |

Inspector |

Male |

Sanitary Inspector |

Secondary character |

|

Ratatouille |

Ambrister |

Male |

Waiter |

Secondary character |

|

Ratatouille |

Horst |

Male |

Subchef |

Secondary character |

|

Ratatouille |

Larousse |

Male |

Cooker |

Secondary character |

|

Ratatouille |

Mustafa |

Male |

Waiter |

Secondary character |

|

Ratatouille |

Talon |

Male |

Lawyer |

Secondary character |

|

Ratatouille |

Django |

Male |

Unknown |

Threshold guardian |

|

Wall-E |

Wall-E |

Male |

Trash compactor |

Hero |

|

Wall-E |

EVA |

Female |

Explorer |

Helper |

|

Wall-E |

M-O |

Male |

Maintenance operator |

Ally |

|

Wall-E |

Captain |

Male |

Ship Captain |

Ally |

|

Wall-E |

Auto |

Male |

Computer |

Shadow |

|

Up |

Carl |

Male |

Retired – exballon’s seller |

Hero |

|

Up |

Russell |

Male |

Student and explorer |

Hero |

|

Up |

Kevin |

Male |

Mother |

Ally |

|

Up |

Charles Muntz |

Male |

Explorer |

Shadow |

|

Up |

Ellie |

Female |

exballon’s seller |

Ally |

|

Up |

Dug |

Male |

Vigilant |

Ally |

|

Up |

Beta y Gamma |

Male |

Vigilant |

Shadow’s helper |

|

Up |

Nurse A.J. |

Male |

Nurse A.J. |

Secondary character |

|

Up |

Nurse George |

Male |

Nurse George |

Secondary character |

|

Up |

Construction manager |

Male |

Construction manager |

Secondary character |

|

Toy Story 3 |

Woody |

Male |

Sheriff |

Hero |

|

Toy Story 3 |

Buzz |

Male |

Astronaut |

Hero |

|

Toy Story 3 |

Andy’s mother |

Female |

Mother |

Herald |

|

Toy Story 3 |

Jessy |

Female |

Cowgirl |

Helper |

|

Toy Story 3 |

Barbie |

Female |

Cowgirl |

Ally/Trickster |

|

Toy Story 3 |

Bonny’s mother |

Female |

Teacher |

Secondary character |

|

Toy Story 3 |

Maintenance operator |

Male |

Maintenance operator and cleaner |

Secondary character |

|

Toy Story 3 |

Lotso |

Male |

Dictator |

Shadow |

|

Cars 2 |

Finn Mcmisile |

Male |

Spy |

Mentor |

|

Cars 2 |

Shiftwell |

Female |

Apprentice |

Ally/helper |

|

Cars 2 |

Mate |

Male |

Crane |

Hero |

|

Cars 2 |

Rayo |

Male |

Race runner |

Herald |

|

Cars 2 |

Miles Axelroad |

Male |

Bussinessman |

Shadow |

|

Cars 2 |

Proffesor Zündrap |

Male |

Gangster |

Threshold guardian |

|

Cars 2 |

Bernoulli |

Male |

Race runner |

Secondary character |

|

Cars 2 |

Sydelli |

Male |

Driver |

Secondary character |

|

Brave |

Fergus |

Male |

King |

Hero |

|

Brave |

Elinor |

Female |

Queen |

Mentor/heroine |

|

Brave |

Mérida |

Female |

Princess |

Heroine |

|

Brave |

Maudie |

Female |

Housekeeper |

Secondary character |

|

Brave |

Dingwall |

Male |

Lord |

Trickster |

|

Brave |

Macintosh |

Male |

Lord |

Trickster |

|

Brave |

Bruja |

Female |

Witch |

Herald |

|

Brave |

MacGuffin |

Male |

Lord |

Trickster |

|

Monsters University |

Mike |

Male |

Student |

Hero |

|

Monsters University |

Sulley |

Male |

Student |

Hero |

|

Monsters University |

Abigail Hardscrabble |

Female |

Doyenne |

Threshold guardian Shapshifter |

|

Monsters University |

Professor Knight |

Male |

Professor |

Secondary character |

|

Monsters University |

Karen |

Female |

Teacher |

Secondary character |

|

Monsters University |

Mrs Squibbles (Mummy) |

Female |

Mother |

Secondary character |

|

Inside Out |

Bill Andersen |

Male |

Boss |

Ally |

|

Inside Out |

Jill Andersen |

Female |

Unknown |

Ally |

|

Inside Out |

Riley Andersen |

Female |

Student |

Heroine |

|

The Good Dinosaur |

Poppa |

Male |

Farmer |

Mentor |

|

The Good Dinosaur |

Momma |

Female |

Farmer |

Secondary character |

|

The Good Dinosaur |

Buck |

Male |

Farmer |

Secondary character |

|

The Good Dinosaur |

Libby |

Female |

Farmer |

Secondary character |

|

The Good Dinosaur |

Arlo |

Male |

Farmer |

Hero |

Source: own elaboration