index●comunicación | nº 11(2) 2021 | Páginas 135-163

E-ISSN: 2174-1859 | ISSN: 2444-3239 | Depósito Legal: M-19965-2015

Recibido el 12_06_2020 | Aceptado el 06_10_2020 | Publicado el 15_07_2021

BRAND PLACEMENT IN MUSIC VIDEOS: EFFECTIVENESS IN UK, SPAIN AND ITALY

EL ‘BRAND PLACEMENT’ EN LOS VIDEOS MUSICALES: EFECTIVIDAD EN REINO UNIDO, ESPAÑA E ITALIA

https://doi.org/10.33732/ixc/11/02Brandp

Sara Piazzolla

Glasgow Caledonian University

Irene García Medina

Glasgow Caledonian University

Marián Navarro-Beltrá

Universidad Católica de Murcia (UCAM)

![]() Para citar este trabajo: Piazzola, S., García, I. y Navarro-Beltrá, M.

(2021). Brand Placement in

Music Videos: Effectiveness

in UK, Spain and Italy. index.comunicación,

11(2), 135-163. https://doi.org/10.33732/ixc/11/02Brandp

Para citar este trabajo: Piazzola, S., García, I. y Navarro-Beltrá, M.

(2021). Brand Placement in

Music Videos: Effectiveness

in UK, Spain and Italy. index.comunicación,

11(2), 135-163. https://doi.org/10.33732/ixc/11/02Brandp

Abstract: Brand placement is used as an alternative advertising strategy. This case study aimed at investigating its efficacy in music videos in the UK, Spain and Italy through surveys. The first research question aimed at determining the degree of association between nationality and brand familiarity. Results have reported a directional association for half the brands advertised. The second research question aimed at determining the correlation between brand familiarity and brand recall. This study demonstrated that the greater the familiarity of the brand, the more likely it is to be recalled after watching a music video. The third research question aimed at determining whether participants were more aware of brands that they had not previously heard of after watching the music videos. Results showed similar responses of participants either agreeing or disagreeing with the statement and similar results were obtained for the Italian and British samples. It could be concluded that brand placement in music videos is especially effective in certain cultures and situations.

Keywords: Brand Placement; Music Videos; Brand Awareness; Brand Recall; Brand Familiarity; Cross-cultural Study.

Resumen: El brand placement es utilizado como una estrategia publicitaria alternativa. Este estudio de caso tuvo como objetivo investigar su eficacia en videos musicales en Reino Unido, España e Italia a través de encuestas. La primera pregunta de investigación tuvo como objetivo determinar el grado de asociación entre la nacionalidad y la familiaridad con la marca. Los resultados mostraron una asociación direccional para la mitad de las marcas anunciadas. La segunda pregunta de investigación tuvo como objetivo determinar la correlación entre la familiaridad con la marca y su recuerdo. Este estudio demostró que cuanto más familiar es una marca, más probable resulta que se recuerde después de ver un video musical. La tercera pregunta de investigación tuvo como objetivo preguntar a los participantes si después de ver el vídeo musical eran más conscientes de las marcas que no conocían. Los resultados mostraron respuestas similares de participantes que estaban de acuerdo o en desacuerdo con la declaración y se obtuvieron resultados similares para la muestra italiana y la británica. Se podría concluir pues que el brand placement en videos musicales es especialmente efectivo en determinadas culturas y situaciones.

Palabras clave: emplazamiento de marca; vídeos musicales; conocimiento de marca; recuerdo de marca; familiaridad de marca; estudio intercultural.

1. Introduction

This study aims at investigating brand placement effectiveness in music videos in three countries. Brand placement has been extensively used as alternative advertising strategy and it is becoming increasingly relevant with the purpose of endorsing brands implicitly in a storytelling context. It could be argued that messages and stories conveyed with the combination of music, prove to be more powerful and effective than traditional advertising messages. As will be seen later, several authors underline the need of empirical research on this subject, especially in the context of music videos and cross-culturally in European regions. Hence, given the considerable amount of research undertaken on the subject of brand placement, and the scarce attention given to brand placement in music videos at a cultural level; this study aims to fill said research gap.

Specifically, this paper is based on carrying out a cross-cultural case study focused on The United Kingdom, Spain and Italy. These countries have been selected for having different cultures. The United Kingdom is part of the Anglo-Saxon culture, Spain belongs to the Francophile culture and Italy has its own culture (Perlitz and Seger, 2004). As an example, Italian and British people are characterized by having a strongly masculine culture (more assertive and less caring and nurturing), by comfortably living with the fact that the future is uncertain and by closely guarding their private space. Just the opposite happens in Spain. Furthermore, in both Spain and Italy, less powerful members of organizations and institutions accept and expect that power can be distributed unequally; a situation that does not occur in the United Kingdom (Perlitz and Seger, 2004).

1.1. Aim and objectives

The aim of this case study is to determine brand placement effectiveness in three European countries -Italy, Spain and The United Kingdom. The following objectives represent how the research will be analysed and discussed to accomplish the main goal:

a) Critically reviewed academic literature on brand placement in music videos, with specific regards to the pop genre and the video clip selected, and providing definitions of brand familiarity, recall and awareness as measures of effectiveness.

b) Conduct an empirical investigation on brand familiarity and nationality as execution factors and their effect on brand recall and awareness as dependent variables, by collecting convenient and limited sample data within the populations of the three countries.

c) Analyse, discuss and compare the collected primary data obtained from the three countries and organise it according to individual factors, dependent variables and countries.

d) Outline limitations of the study, draw conclusions and suggest further opportunities for research.

1.2. Background of brand placement in music videos

Brand placement is recognised by Karrh (1998) and Ginosar and Levi-Faur (2010) as a relatively recent advertising strategy generated from the need of marketers to infiltrate advertising clutter, pursuing a natural and implicitly not-profit driven content incorporation (Mikołajczyk, 2015). Solomon and Englis (1994) introduce for the first time the term «reality engineering» to describe the effort of marketers to shape social images that represent areas of public life through popular cultural vehicles; a definition that can be naturally integrated into Karrh’s (1998) notion of consumer acceptance of brand images, considered consumption symbols, as part of everyday life.

A comprehensive definition of brand placement is:

Product placement -also known as product brand placement, in- program sponsoring, branded entertainment, or product integration -is a marketing practice in advertising and promotion wherein a brand name, product, package, signage, or other trademark merchandise is inserted into and used contextually in a motion picture, television, or other media vehicle for commercial purposes (Williams et al., 2011, p. 2).

Van Reijmersdal, Neijens and Smit (2007) argue that visual arts and entertainment, such as tv series, shows and songs allow marketers to reach a wider audience given their distinctive repeatability. The author further discusses how brand placement in the mentioned media channels is rather effective due to the amplifying factor of associating a popular actor or artist with the product advertised (Williams et al., 2011), hence providing promotional strength to the brand and increasing its awareness and purchasing potential. People prefer to be able to communicate directly with companies and feel empowered in establishing their interests in online communities (Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2004), which can be addressed by creating valuable online content that attracts viewers and reaches their hearts and minds (Falkow, 2010 as cited in Williams et al., 2011). Omarjie and Chiliya (2014) state that brand placement strategies in music videos have increased, specifically in the pop, rap and RnB genres, and suggest that the launch of YouTube in 2005 and fast internet connection already available on new smartphones provide straightforward access to music videos (Plambeck, 2010), offering marketers a lucrative, yet less expensive, medium to advertise brands to targeted consumers.

1.3. The background of brand familiarity and recall across cultures

There is controversy when assessing the monetary value of brand placement in music videos, given that no sophisticated model has been developed by practitioners (Craig‐Lees, 2008). For this reason, Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan (2006) have developed a comprehensive and integrative framework for academics and practitioners to contribute to academic literature in the attempt to collect data based on various execution and individual factors, processing and effects of brand placement, through a combination of certain stimuli.

Regarding individual-difference factors, brand familiarity will be assessed across cultures. «Brand familiarity is a unidimensional construct that is directly related to the amount of time that has been spent processing information about the brand, regardless of the type or content of the processing that was involved» (Baker et al., 1986). Nelson (2002), Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan (2006) and Omarjee and Chiliya (2014) argue and demonstrate with their respective studies that brand familiarity has an effect on brand recall, i.e. they argue it is a contributing factor in remembering and recognising brands displayed or mentioned in branded entertainment. Brand familiarity «captures consumers’ brand knowledge structures, that is, the brand associations that exist within a consumer’s memory» (Campbell and Keller, 2003, p. 293) and is defined as the extent to which a brand is well-known or not. Thus, it is argued that cultural context will have a significant role in determining how familiar certain brands are compared with others in different countries.

A noteworthy mention in terms of placement modality is required to justify the choice of the music video employed in the research study. Extensive literature on brand placement in movies shows higher levels of brand recall when the product was mentioned and showed, since the dual-coding factor enhances audio-visual placement effectiveness (Bressoud, Lehu and Russell, 2010). However, in the literature available for product placement in music videos, visual placement has showed higher recall than combined audio-visual or audio placements (Plambeck, 2010).

In terms of information processing, explicit aided memory recall measures will be adopted. Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan (2006) argue that explicit memory is recorded by direct tests of recall, where intentional effort is made by participants to recollect information from recent stimuli. Brand recall, which can be defined as the «consumers' ability to retrieve [a] brand when given the product category, the needs fulfilled by the category, or some other type of probe as a cue» (Keller, 1993, p. 3), has been frequently employed in previous literature as cognitive measure of effectiveness (Chan, 2012). It can be argued that this effect from placement, as outlined by Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan (2006), is the most recurring one in determining brand placement effectiveness. Although extensive literature is available for brand placement recall in movies and tv programmes, there is sporadic empirical research on music videos as the media vehicle in brand placement (Krishen and Sirgy, 2016). Karrh (1998) further argues that brand recall measures are more appropriate for explicit, hence for more conscious test processing rather than implicit unconscious processing. Brand memory is influenced, as stated, by brand familiarity and it is premise for consequent brand awareness, that is, for «a rudimentary level of brand knowledge involving, at the least, recognition of the brand name» (Hoyer and Brown, 1990, p. 141). As stated by Omarjee and Chiliya (2014) and Macdonald and Sharp (2003), the music-video brand placement stimuli positively contributed to participant’s awareness of recalled brands, which will be consequently introduced in the consumer’s consideration set at the moment of purchase, hence improving chance for purchase intention after exposure.

According to Chan (2012) there is scarce literature available on cross-cultural studies outside The United States of America and, therefore, identifies a need for further empirical research to assess brand placement effectiveness cross-culturally. Thus, assessing brand familiarity for the brands placed in the music video shown to participants of three different cultures, to then deduct consequent brand awareness after exposure and explicit recall testing, is deemed to contribute to international advertising communication measures for global brands.

2. Literature review

Hudders et al. (2012) point out that consumers feel increasingly overwhelmed by advertisement messages and commercials across traditional media channels and argue that it is for this reason that marketers are seeking new opportunities to develop innovative strategies to reach potential customers effectively. Brand placement represents an effective advertising strategy and an alternative to traditional advertising. The importance of which has been accentuated over the years. Chan (2012) asserts the relevance of cultural studies on this subject with the purpose of outlining differences and similarities among cultures, regarding brand familiarity and awareness.

2.1. Brand placement in music videos

Newell, Salmon and Chang (2006) identify the first ever recorded brand appearance of a UK soap manufacturer, «Lever Brothers», in a Lumière film in 1896. Despite sporadic product integrations throughout the following years, the phenomenon of brand placement was formally coined and identified in the 1980s (Chan, 2012). Brand placement became widely used as an advertising strategy after the first most successful incorporation of Reese’s Pieces in the 1982-movie E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, with a registered sales increase of 65% within a month (Tsai, Wen-Ko and Liu, 2007).

As Karrh (1998) anticipated in his progressive brand placement review, brands are increasingly incorporated in mass media content. Due to consumer sophistication (Chan, 2012), media fragmentation and proliferation, a predictable decay in traditional advertising efficacy and zapping, consumers’ resistance towards adverts (Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan, 2006), it is argued that brand placement continues to be an important and effective strategy within advertising to reach targeted consumers and non-users (Mackay et al., 2009; The Economist, 2005). Matthes, Schemer and Wirthet (2007) report that factors including, but not limited to, the message being embedded in the editorial content, the transformational nature with high levels of disguise and obtrusiveness and the likelihood to be processed empathetically, represent advantages of placement strategy effectiveness when compared to traditional advertising measures. A systematic review on brand placement collects a relatively comprehensive archive of definitions, highlighting different nuances of interpretation in previous literature (for further reading see Chan, 2012).

This riskier, however increasingly common, practice is integrated into mainstream media, including, films, TV programs, video games and music videos (Stephen and Coote, 2005). Advertisement in the music industry has started from the creation of commercials visually and audibly similar to music videos, given the overlapping of creatives (Pendleton, 1988), where such similarity led to defining music videos «infotainment» or «advertorials» (New York Times, 1989 as cited in Englis, Solomon and Olofsson, 1993), to then develop into «song product placements», «Adsongs» including a sponsor’s name, subsequently sold on radio airtime and available on compact disk and cassette for the public (Wriite Radio Adsong, 1997 as cited in Karrh, 1998).

From the launch of MTV-Europe in 1987, the music industry has deeply changed with the evolution of technology, enabling consumers to discover and listen to music by streaming online without the need of purchasing physical products (IbisWorld, 2019), with streaming subscriptions revenue figures for £516m in 2018, compared to £241m in physical formats (Mintel, 2019). The IBIS report further states that product endorsements are increasingly widespread with artists incorporating specific brands in their music videos and marketers seeking to gauge consumer trends for accurate targeting. YouTube’s popularity overshadows the free music streaming apps in the market segment, which results in 83% of UK population preferring this music-listening platform (Mintel, 2019).

Both Chang (2003) and Schemer et al. (2008) assert the increasing importance of the trend of brand placement in music videos, since it reduces the production costs of music videos (Roozen and Claeys, 2009) and, equally important, it offers competitive advantage because music videos evoke both emotions (Englis, 1991) and a certain involvement with the video narrative and artist (Sun and Lull, 1986). Plambeck (2010) reported Mr. Caraeff’s, ex Vevo CEO, and Mr. Feldman’s, Vice President, Brand Partnerships & Sports Marketing at Atlantic Records, views on brand placement in the music industry, who argue that Lady Gaga’s «Telephone» YouTube video shows complementarity in a successful collaboration between brands and music companies and highlight another advantage of this practice, being the permanence of brands placed in the video rather than disappearing in its prior 15-second ad. According to a PQ Media report in 2010 as cited in Plambeck (2010), overall paid product placement declined 2.8 percent, while the money invested in product placement in music videos grew 8 percent compared to the previous year. Despite the rise of product placement practices in music videos, only a handful of studies have conducted empirical and correlational research on this subject (Krishen and Sirgy, 2016).

2.2. Brand familiarity and recall as measures of effectiveness

Russell and Belch (2005) clarify that industry practitioners have just recently started to address the issue of effectiveness measures in product placement, whose tools and key measurement formulas, whether they focus on monetary value or outcome-oriented assessments, have yet to be systematically determined. Carr (2005) further discusses this consideration, arguing that although several dependent measures are employed to assess effects on consumer audiences, from traditional hierarchy of effects to attitudes, these would inevitably fall into measures of traditional advertisement effectiveness, hence asserting that there is currently no sophisticated operating model for product placement evaluation.

In this study, brand recall will be employed, since it is the most pragmatic dependent variable, frequently used to determine placement effectiveness (Chan, 2012; Karrh, 1995; Russell and Belch, 2005). Recall is assessed as a cognitive processing measure, where respondents are required to respectively retrieve information or opinions and judge whether or not a certain stimulus has been previously seen (Brennan, Dubas and Babin, 1999; Nelson, 2002). Karrh (1995) reports that product placement practitioners consider the measure of aided recall to be important, a measure that assesses recall after the participant has been provided with a cue. Rossiter and Percy (1983) note that brand awareness is the most basic communication variable influenced by brand placement in the traditional hierarchy of effects, with an ultimate increment in sales. Brand awareness is defined by Alba and Chattopadhyay (1986) as the prominence of a brand in memory, hence its enhanced salience in a specific product category may obstruct recall of competing brands. As a result, since it is argued that individuals do not continue expanding their evoked sets, an increased salience of one brand might cause others in the same product category to be excluded from the consideration set (Moran, 1990). Finally, Babin and Carder (1996) assert that awareness varies on a spectrum from recognition to recall, which allows the consumer to identify the brand at the moment of purchase.

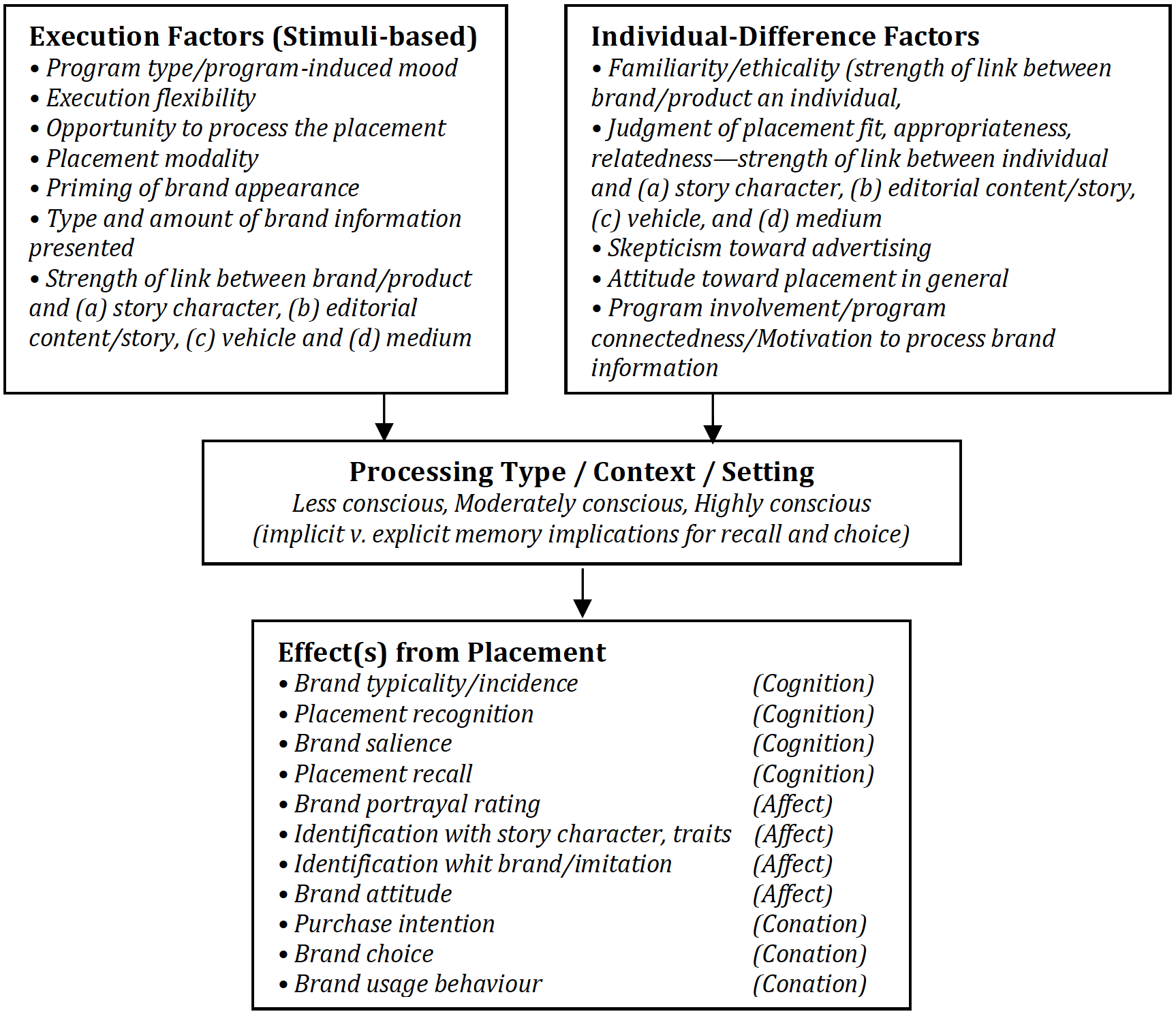

In terms of individual factors, Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan (2006) claim that brand familiarity has an effect on placement recall (see figure 1). Regarding brand familiarity Brennan and Babin (2004) note that since familiar brands produce stronger product categories associations, they are more accessible in memory. However, Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan (2006) report that the phenomenon known as Von Restoff effect (Wallace, 1965) or the isolation effect (Huang, Scale and McIntyre, 1976) may influence the recall of brand placements (Balasubramanian, 1994).

Figure 1. The proposed model framework

Source: Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan (2006).

The rationale upholding this statement is that unfamiliar stimuli are less expected, hence attract superior attention and produce higher recall (i.e. cognitive outcome) than familiar stimuli. Nelson (2002) found evidence of said hypothesis, by demonstrating that brands regarded as less familiar by participants are recalled better. Thus, it is argued that consumers that are more accustomed to see well-known brands, may decrease their attention when exposed to familiar brand placements.

With regards to modality, Smith’s (1985) classification is regarded by Chan (2012) as the «simplest and most exclusive one»: three placement groups are divided into visual, audio and combined audio-visual. There is extensive research asserting that visual- or audio-only placements might be unnoticed by the viewers, hence leading to lower brand recall and recognition (Argan, Valioglu and Argan, 2007; Gupta and Lord, 1998; Law and Braun, 2000; Van Reijmersdal, Neijens and Smit, 2007). However, it can be argued that these studies were testing tv programmes and movies as stimuli and so it may not be possible to generalise these results in other media. Some research has showed mixed results of effectiveness (Lord and Putrevu, 1993) and in a more recent study, specifically where music videos were used as stimuli, visual product placement prominence resulted to be more effective than subtle or audio-only placement (Roozen and Claeys, 2009). For this reason, in this study the stimuli music video includes visual-only product placements.

2.3. Cross-cultural studies

In 1983, White argued that the international popular music industry was expanding with the purpose of overcoming national and cultural barriers worldwide. A Passport report containing recent data acquired in the past five years from Italy, Spain and The United Kingdom reports respectively 24, 20 and 25 million YouTube active monthly users in 2018 (Euromonitor International, 2019). Chan’s (2012) review highlights the need to analyse product placement effectiveness across cultures, given the limited research conducted in the past years, which has rarely focused on non-US cultural environments (Tiwsakul and Hackley, 2009). The importance of further investigation has been subject to mention in previous literature, where scholars and practitioners believe that placement effects might vary according to macro-cultural factors (Homer, 2009; Karrh, 1998; Stern and Russell, 2004), hence conducting large-scale quantitative studies is highly recommended (Tiwsakul, Hackley and Szmigin, 2005) to provide further guidance on standardisation and adaptation practices in marketing communication (Gould, Gupta and Grabner-Kräuter, 2000).

Previous literature states that placement is a form of marketing communication, its effects may be influenced by communication approaches and societal-level factors that shape consumers’ cultures, hence their responses to advertising (Okazaki, Mueller and Taylor, 2010). The international trait of brands makes them appealing to more cultures according to the brand values, image and availability in that country (Kotabe and Helsen, 2004). Whether a brand is well-known or not, depends on the brand perception from different cultures, the advertising broadcasted in said countries and their availability at the point of purchase. Hence, an increase in brand awareness of specific brands, after stimuli exposure through brand placement in music videos, might have a positive effect in the overall communication strategy in global brand management (Kotabe and Helsen, 2009).

In this case study, the effect of brand familiarity will be analysed cross-culturally in terms of its impact on brand recall. Brand familiarity might impact differently on cultures according to their previous knowledge and perception about the brands advertised in the music video (House et al., 2004). Chan, Petrovici and Lowe (2016) further suggest adopting a cross-cultural approach in understanding international advertising practices as brand media vehicles. This empirical study aims at contributing to international communication strategy research, with the purpose of assessing if brand placement in music videos is a viable choice for marketers to advertise fewer familiar brands to a cross-cultural audience, in order to increase their brand awareness, and ultimately enhancing their purchase intention.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research strategy

As anticipated in the introduction chapter, this case study aims at understanding and determining whether there are differences in brand familiarity and recall of brand placement in music videos within three European cultures. The strategy adopted in this case study is the survey and will be conducted by employing free-of-charge online forms to gather data. The survey will be distributed among the network of acquaintances that the researchers have in several workplaces in the three selected countries (The United Kingdom, Spain and Italy) between March and April 2020. Firstly, respondents will answer sociodemographic and brand awareness questions. Secondly, the respondents will watch the music video «Telephone» by the artist Lady Gaga on YouTube. A link of the video was be available in the survey. As previously commented, this music video shows complementarity in a successful collaboration between brands and music companies. Specifically, this music video has been chosen for being one of the most representative of the use of brand placement (Rodriguez-Lopez and Perez-Rufi, 2017). In fact, it has caught the attention of the academy and has already been used to study, for example, if the third-person effect is related with the viewing of products in video clips (Schmidt, 2011) and if the effects of brand-unspecific product placement disclosures are moderated by product placement frequency (Matthes and Naderer, 2015). Finally, the respondents will answer questions about brand placement. The online survey has been prepared, adapted and translated by the researchers. A relevant point to mention involves the amount of extra time required for cross-cultural comparative studies, given the complexity of research scale’s construct and equivalence (Cadogan, 2010). Thus, ensuring adaptation of research procedures, instruments and scales across cultures, especially when language translation is required (Chan, 2012) are considered to be highly significant.

3.2. Data collection techniques

This case study will adopt quantitative research design, given the nature of its research strategy and its versatile applicability in an international-online context described above. This is a mono method quantitative study, where survey questionnaires will be distributed to non-probability convenience sampling respondents through Google Forms questionnaires and the type of questions will be designed as multiple choice[i]. Walsh et al. (2015) underline the association between the positivist philosophy and quantitative research methods, hence further justifying this choice.

Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill (2019) argue that the questionnaire is the most commonly used data collection method within the survey strategy, and since each respondent answers the identical set of questions, it represents an effective way of gathering responses from a large sample. Using this method will aid the researchers in better collecting and quantifying data, making it possible to generalise results beyond the sample and applying them to the population (Galpin and Krommenhoek, 2013).

The quantitative research design is thus believed to be the most appropriate and useful when examining measures of brand placement effectiveness of brand recall in a cross-cultural context, on which hypotheses will be based. Furthermore, given the size and extent of the research to undertake, and the translation of the questionnaire, a self-completed quantitative survey research design will be more practical and manageable for the researchers in the collection and analysis of data among three cultures.

3.3. Analysis framework

IBM SPSS Statistics will be employed as the chosen statistical analysis software and Google Forms will be used to design and distribute the online questionnaires across the three countries (Field, 2013). Excel will also be used to examine the information collected. Data will be analysed with the support of these statistical frameworks to draw graphs and diagrams, which will facilitate data visualisation to compare data and reach conclusions (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, 2019). Using said frameworks will help when organising the data collected and classifying them into categories of nationality according to variables of brand familiarity, nationality, brand recall and brand awareness and their correlation. Aforementioned themes will be discussed from gathered data in order to contribute to research with generalisable results, to prove or disprove hypotheses.

4. Findings and discussion

4.1. Report on sample

The questionnaire collected responses from 115 respondents, 33 of which are British, 35 are Spanish and 47 are Italian. In terms of gender there is a female prevalence among respondents, 39 are male and 4 transgender participants. With reference to age, it should be noted that the majority of the respondents are young (see table 1).

|

Nationality |

Age |

Gender |

|

British = 33 |

18-24 years old = 39 |

Male = 39 |

|

Spanish = 35 |

25-34 years old = 28 |

Female = 71 |

|

Italian = 47 |

35-44 years old = 17 |

Transgender = 4 |

|

|

45+ years old = 31 |

Prefer not to say = 1 |

Source: self-made.

4.2. Brand familiarity and nationality

The chi-square statistic[ii] has been employed to test the relationship between the categorical variable of nationality with the independent variables of each brand’s familiarity recorded in the questionnaire.

Table 2 shows the percentage of brand familiarity (B.F.) organised according to the respondents’ nationality. Each brand familiarity percentage is matched with the corresponding chi-square value, in brackets, against the three nationalities. The statistical significance is also reported.

Table 2. Nationality and brand familiarity

|

Nationality |

Virgin mobile B.F. |

Dr. Martens B.F. |

Ray ban B.F. |

Beats B.F. |

Doom B.F. |

Coke diet B.F. |

Chanel B.F. |

Miracle whip mayo B.F. |

|

British |

23.5% (33.09) *** |

22.6% (6.34) * |

23.5% (6.50) * |

23.5% (21.12) *** |

7.8% (9.57) * |

26.1% (24.17) *** |

23.5% (4.32) |

7.8% (12.06) ** |

|

Spanish |

14.8% (33.09) *** |

16.5% (6.34) * |

23.5% (6.50) * |

16.5% (21.12) *** |

7.8% (9.57) * |

15.7% (24.17) *** |

21.7% (4.32) |

2.6% (12.06) ** |

|

Italian |

7.0% (33.09) *** |

31.3% (6.34) * |

39.1% (6.50) * |

12.2% (21.12) *** |

1.7% (9.57) * |

14.8% (24.17) *** |

36.5% (4.32) |

0.9% (12.06) ** |

***p<.001 | **p<.005 | *p<.05

Source: self-made.

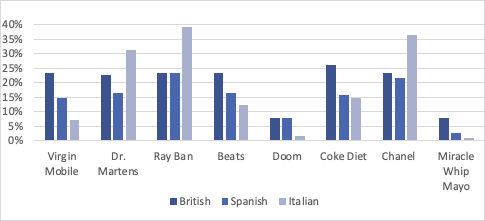

Figure 2 displays the brand familiarity percentages reported above for each nationality, with the purpose of providing visual support to the discussion that follows.

Figure 2. Brand familiarity per nationality

Source: self-made.

The outcomes have been organised according to the type of results obtained from the questionnaire, rather than following their display order in the table and chart above. The first research question aims to determine whether nationality, in this case used as indicator to associate the nations’ participants to their corresponding cultural contexts, can be considered a predictor of brand familiarity, i.e. if a person’s nationality has an impact on their knowledge of certain brands due to the brand’s availability and communication strategy in that specific country.

The results regarding the brands Virgin Mobile, Beats, Coke Diet and Miracle Whip Mayo report a significant (p<.001 – p<.005) directional association between nationality and brand familiarity, with chi-square values ranging from 33.09 and 12.06. These demonstrate that the three different nationalities contribute to the prediction of brand familiarity for four of the eight brands placed in the music video, thereby rejecting the null hypothesis of independence between the two variables. Conversely, a significant directional association between nationality and brand familiarity is observed in Dr. Martens, RayBan and Doom. For Chanel, the directional association is insignificant, showing that there is little association between nationality and brand familiarity. In this case, the chi-square values are between 9.57 and 4.32. Therefore, these results demonstrate that three different nationalities do not influence brand familiarity scores for the other four brands placed in the music video, thereby accepting the null hypothesis of independence between the two variables. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that, although the brands advertised do not belong to the same company or corporation, there appears to be a product category similarity among the eight brands allocated in the two association groups. Notably, Virgin Mobile and Beats can be categorised as technology-related brands, Coke Diet and Miracle Whip Mayo as food-related brands and Dr. Martens, Ray Ban, Doom and Chanel as fashion-related brands. This association may suggest that the communication plan of technology and food brands is focused on a national-based strategy, whereas the communication strategy of fashion brands is based on an international approach.

In terms of brand familiarity percentages, a noteworthy difference for each brand highlights how certain brands are generally more recognised than others, regardless of their nationality, and how others are strictly dependent from their popularity, the degree of widespread familiarity with the brand, in that specific country. Specifically, Virgin Mobile (23.5%), Beats (23.5%), Coke Diet (26.1%) and Miracle Whip Mayo (7.8%) are brands that are more familiar to the British sample; Dr. Martens (31.3%), Ray Ban (39.1%) and Chanel (36.5%) are better known to the Italian participants; the Spanish participants report interesting results, which are harder to categorise. Results demonstrate that Spanish participants have an overall medium score of brand familiarity. In some cases, this is higher than the brand familiarity for Italian participants (Virgin Mobile 14.8%, Beats 16.5%, Doom 7.8%, Coke Diet 15.7% and Miracle Whip Mayo 2.6%). In some cases, the brand familiarity score for Spanish participants is close to the score for British participants. For some brands the scores are equal for British and Spanish participants (Ray Ban 23.5% and Doom 7.8 %).

Overall, the results demonstrate that the brands that have recorded a lack of association, namely Dr. Martens, Ray Ban and Chanel are familiar to all three nationalities, or equally unfamiliar (Doom), and that their advertising strategy and product availability across these countries is consistent.

4.3. Brand familiarity and brand recall

The analysis of the data related to this research question required the use of chi-square as well, and it was employed to test the relationship between each the value of brand familiarity with the correspondent brand recall scores recorded in the questionnaire. The data refers to overall results for these two variables without taking into consideration nationality as a differential factor. The percentage shown refers to the 103 participants that answered «Yes» to question number 6: «Have you seen any brands/products in the music video you just watched?», used as an indicator of overall brand recall.

Table 3 shows the percentage of brand familiarity for each brand, the corresponding brand recall percentage and the percentage of people that were familiar with the brand but did not recall it. The statistical significance and the chi-square value, in brackets, are also reported.

Table 3. Brand familiarity and brand recall

|

Brand Familiarity |

Brand |

Brand |

|

|

Virgin Mobile |

47.3% |

34.0% (4.20)* |

9.7% |

|

Dr. Martens |

71.8% |

24.3% (2.76) |

47.6% |

|

Ray Ban |

91.3% |

48.5% (1.29) |

42.7% |

|

Beats |

53.4% |

38.8% (32.37)*** |

14.6% |

|

Doom |

16.5% |

0.0% (.61) |

16.5% |

|

Coke Diet |

55.3% |

36.9% (15.02)*** |

18.4% |

|

Chanel |

85.4% |

27.2% (4.00)* |

58.3% |

|

Miracle Whip Mayo |

8.7% |

5.8% (7.76)** |

2.9% |

***p<.001 | **p<.005 | *p<.05

Source: self-made.

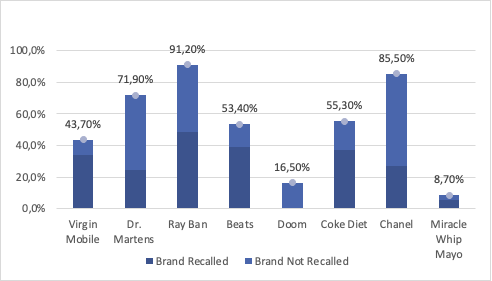

Figure 3 displays the information provided in the table above, with the purpose of providing visual support to the discussion that follows. The percentages represented refer to the brand familiarity scores against the brand recall values for each brand.

Figure 3. Brand familiarity and brand recall

Source: self-made.

The second research question aims at validating Nelson’s (2002) findings on the correlation between brand familiarity and brand recall, i.e. the more familiar a brand is, the less likely it is to be recalled after stimuli exposure. These findings have been upheld by Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan (2006), in reference to the Von Restoff effect introduced by Wallace (1965), who claims that unfamiliar stimuli will be less expected and for this reason, they will attract more attention than familiar stimuli, thus they will be recalled better.

The results regarding Virgin Mobile (34.0% brand recall against 47.3% brand familiarity), Ray Ban (48.5% against 91.3%), Beats (38.8% against 53.4%), Coke Diet (36.9% against 55.3%) and Miracle Whip Mayo (5.8% against 8.7%) report a high brand familiarity-brand recall ratio. These findings provide further empirical support to Brennan and Babin’s (2004) study, which claims that familiar brands produce stronger product categories associations, making them more accessible for the memory. In other words, these results assert that, for the brands reported above, the higher the brand familiarity, the more likely they are proven to be recalled. Nevertheless, the reported findings contradict Nelson’s (2002) hypothesis of opposite correlation between the two variables, hence providing empirical support to its counterargument.

Conversely, results regarding Dr. Martens (24.3% brand recall against 71.3% brand familiarity), Doom (0.0% against 16.5%) and Chanel (27.2% against 85.4%) report a low brand familiarity-brand recall ratio, hence confirming Nelson’s (2002) hypothesis of opposite correlation. In other words, for the abovementioned brands, the higher the brand familiarity, the lower the brand recall values after stimuli exposure. Furthermore, Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan’s (2006) argument regarding the von Restoff effect, is also reinforced by these findings, demonstrating that participants that were familiar with Dr. Martens, Doom and Chanel, were not able to recall them after exposure, due to the lack of a surprise effect while watching the music video. On the other hand, these results exhibit contradictory findings in regard to Brennan and Babin’s (2004) study, proving that, for these specific brands, familiarity produced weaker product categories association, making them less accessible in memory.

The research available on this subject is based upon the assumption that there is a correlation between the two variables of brand familiarity and brand recall. In this study, the researcher has considered this assumption and tested it with 8 chi-square tests for each brand, with the objective of verifying this hypothesis with empirical data. The results reported for the brands Beats and Miracle Whip Mayo demonstrate that there is a directional association between the two variables, albeit not significantly larger than expected values; namely Beats chi-square expected value was 22.37, compared with the actual outcome of 32.37, and Miracle Whip Mayo chi-square expected value being 2.45, compared with the relatively higher outcome of 7.76. In regard to the other six brands placed in the music video, there appears to be no correlation between brand familiarity and brand recall scores, as the individual chi-square tests suggest that the results obtained are largely due to chance. These results may question the validity of the hypothesis of correlation between the two variables, hence confirming that brand familiarity has no impact on brand recall, as well as the proportionality between the two.

Overall, the prevalent results demonstrate that five out of eight brand recall percentages, namely Virgin Mobile, Ray Ban, Beats, Coke Diet and Miracle Whip Mayo, represent a large portion of their corresponding brand familiarity scores, hence suggesting a directional correlation between the two variables; the more familiar a brand is, the higher are the chances for its recall after brand placement.

4.4. Brand recall and brand awareness

In regard to the third and last research question, the results provided by Google Forms responses and further Excel analysis have allowed the researchers to gather the following data for discussion. The last question asked in the survey, question number 8 «Do you agree with the following statement: ‘After watching this music video, I am more aware of brands I did not know’?», aimed to ask the respondents a direct question that required judgement and reflection after watching the video and completing the questionnaire.

Considering the abovementioned 103 respondents, that have stated positive brand recall after watching the music video, results on brand awareness are relatively similar for positive and negative responses. 53 respondents confirm that their knowledge about previously unfamiliar brands has improved after watching the video, while 50 respondents disagree with the statement above, thus considering their brand awareness towards unfamiliar brands unchanged after stimuli exposure. It can be argued that the influence of brand placement on recall at the point of purchase is categorised as an unconscious process, thus respondents that rationally disagree with that statement might be influenced by brand placement without acknowledging or even realising it at the moment of purchase.

These overall brand awareness results have been further analysed against nationality, employed as differential factor, to identify any differences between brand awareness scores among the three countries. The British respondents are significantly inclined to believe that their knowledge about previously unfamiliar brands has improved after watching the music video, reporting a strong percentage of 59.3% of positive brand awareness against 40.7% of those British respondents rejecting the statement. The Italian sample shows scores similar to the British sample, reporting a lower 55.3% of Italians agreeing to the statement against a 44.7% of respondents stating an unvaried brand awareness of unfamiliar brands after stimuli exposure. On the other hand, the Spanish participants differ from the Italian and British samples. The majority of the respondents, namely 62.1% of the total of the Spanish sample, disagrees with the notion of being positively influenced by brand placement in the music video in terms to their knowledge about unfamiliar brands, while only 37.9% of them believes to be more aware of unfamiliar brands after watching the video.

Rossiter and Percy (1983) assert that brand awareness is the variable that is firstly influenced by brand placement in the traditional hierarchy of effects, with the ultimate purpose of increasing sales for the brand advertised. Overall, the eight brands placed in the music video have been positioned with the purpose of increasing both brand awareness and contribute to decision making at the point of purchase. It can be argued that according to the results obtained, 53% of participants are more aware of these brands and possibly will be influenced by these brand placement strategies in their future decision-making processes, when considering a purchase within that product category. The majority of the British and the Italian participants believe, as Alba and Chattopadhyay (1986) argue, that these placements have contributed to a prominence of these brands in their memory, thus enhancing the salience in these specific products’ category, with the possibility of obstructing recall of competing brands. Conversely, most Spanish respondents do not consider the exposure to brands placed in the music video as a contribution to their evoked sets of brands in that product category, thus possibly being not consciously influenced in their decision making at the moment of purchase of said brands.

Another relevant mention in terms of the results obtained is the percentage of people that have declared their tendency to notice brands in music videos and the corresponding portion that actually noticed brands in this specific music video. 14.8% of all respondents do not tend to notice brands in music videos and actually did not recall any in the music video used in the study, while 49.6% of the respondents admit their usual tendency to notice brands in music videos, and then recalled them in the video used in the study. These results suggest that there is a considerable percentage (26.9%) of respondents, who, although they do not tend to notice brands in music videos, then they did recall some in this case.

5. Conclusions, limitations and recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

The aim of this case study was to contribute to academic literature, by providing empirical evidence of several variables that influence brand placement effectiveness in music videos. The literature review outlined previous research regarding brand placement in music videos, presenting how different variables contribute to brand placement effectiveness, and introduce the subject of culture used as a variable in the study. The significance of brand memory and brand awareness has been demonstrated with the purpose of correlating them to the concepts of brand familiarity and nationality, variable used as measurable alternative to culture. The researchers have conducted primary quantitative data collection to verify the extent of the correlation between nationality and brand familiarity, and how this ultimately impacts on brand awareness through brand recall.

As for the first research question, the objective was to determine the impact nationality has on brand familiarity. Findings showed a directional association for Virgin Mobile, Beats, Coke Diet and Miracle Whip Mayo between the variables of nationality and brand familiarity and a lack of association for Dr. Martens, Ray Ban, Doom and Chanel. This suggests a possible product category correspondence of results, demonstrating a national advertising strategy for two technology-related brands and two food-related brands, and an international advertising strategy for four fashion-related brands.

In terms of the second research question, the goal was to discover whether the previously tested hypothesis of correlation between brand familiarity and brand recall is validated for this study and to assess the directionality of association between the two variables. Results have demonstrated that there is an actual correlation between their brand familiarity and brand recall scores only for the brands Beats and Miracle Whip Mayo. These results are consistent with Brennan and Babin’s (2004) study that hypothesises a directional association between the two variables; for the abovementioned brands, the more familiar they are to respondents, the higher the chances for their recall after stimuli exposure.

The last research question aimed at identifying a conscious correlation from respondents between brand recall of unfamiliar brands and their consequent brand awareness. Previous research has recognised the importance of brand awareness, as a key factor contributing to an ultimate increase in sales for the brand. When asking respondents to determine whether they believe their brand awareness of previously unfamiliar brands had increased after watching the music video, similar results have been reported for both positive and negative answers among all the eligible respondents. On the other hand, when introducing nationality as differential variable, the majority of the Italian and British respondents consciously reported that their knowledge about previously unfamiliar brands had increased after brand exposure in the music video, whereas the prevalent opinion among Spanish participants disagrees with the statement.

Finally, it could be concluded that, the greater the familiarity of the brand, the more likely it is to be recalled after watching a music video. Therefore, brand placement in music videos does not seem to be a viable choice for marketers to advertise fewer familiar brands to a cross-cultural audience in order to increase their brand awareness, and ultimately enhancing their purchase intention. It seems to be more advisable to include brands that are known to the audience. Moreover, it could be said that brand placement in music videos contributes to a prominence of these brands in the memory of British and Italian participants only. This situation could later favour the purchase of these brands for said participants. Therefore, it could be concluded that brand placement in music videos is especially effective in certain cultures and situations.

5.2. Limitations

The study resulted in the collection of questionnaire responses from only 115 respondents, factor which may hinder the possibility of findings generalisation. Moreover, the sample obtained is not equal by age (39 people between 18-24 years old, 28 between 25-34 years old, 17 between 35-44 years old and 31 more than 45 years old), gender (39 male, 71 female, 4 transgender and 1 person who preferred not to say) and country (33 respondents from The United Kingdom, 35 respondents from Spain and 47 respondents from Italy), which leads to a possible imbalance in the analysis undertaken on the total number of participants. Another limitation was the scarce research available on quantitative cross-cultural studies, thus the researchers have reported the findings of culture literature in this study and formulated a hypothesis to demonstrate with the conducted survey.

5.3. Recommendations for future research

Throughout the analysis undertaken for the study, the researchers have identified several opportunities for further research on this subject. The Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan’s (2006) framework provides several alternatives of variables available in terms of execution factors, individual factors, processing and effects from placement which take into consideration cognitive, affective and conative effects. This study has only focused on cognition effects, however, there is a widespread interest in affective outcomes (see Chan, 2012), which would require testing for brand attitudes, thus highlighting influencing factors, such as likeability of the artist, identification with the character, storytelling involvement, product category interest, while using culture as differential factor. The music video contained more brands than the eight employed in the research, so it could be interesting to extend the study to all the brands placed in the music video, with brand prominence categorisation. If replicated, the study could then provide non-gradient scales and open questions to identify topics of interest and obtain samples that are more similar by age and gender to analyse results by using these variables as differential factors, as different ages and genders are susceptible to distinct appeals and modalities, according also to the product type advertised. Another possible line of investigation could include the identification of the viewer with the brand. Finally, given the importance of unconscious processing, further research could address brand awareness, by testing the respondents in the shopping environment, in regard to the decision-making process, to determine brand placement effectiveness as contributing factor to an increase in sales.

Bibliographic references

Alba, J. W. & Chattopadhyay, A. (1986). Salience Effects in Brand Recall. Journal of Marketing Research, 23(4), 363-369. https://bit.ly/3buR6Fe

Argan, M., Velioglu, M. N. & Argan, M. T. (2007). Audience Attitudes Towards Product Placement in Movies: A Case from Turkey. Journal of American Academy of Business, 11(1), 161-167.

Babin, L. A. & Carder, S. T. (1996). Viewers' Recognition of Brands Placed Within a Film. International Journal of Advertising, 15(2), 140-151. doi.org/10.1080/02650487.1996.11104643

Baker, W., Hutchinson, J. W., Moore, D. & Nedungadi, P. (1986). Brand Familiarity and Advertising: Effects on the Evoked Set and Brand Preference. NA-Advances in Consumer Research Volume, 13, 637-642.

Balasubramanian, S. K. (1994). Beyond Advertising and Publicity: Hybrid Messages and Public Policy Issues. Journal of Advertising, 23(4), 29-46. doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1943.10673457

Balasubramanian, S. K., Karrh, J. A. & Patwardhan, H. (2006). Audience Response to Product Placements: An Integrative Framework and Future Research Agenda. Journal of Advertising, 35(3), 115-141. doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367350308

Brennan, I. & BabiN, L. A. (2004). Brand Placement Recognition: The Influence of Presentation Mode and Brand Familiarity. Journal of Promotion Management, 10(1-2), 185-202. doi.org/10.1300/J057v10n01_13

Brennan, I., Dubas, K. M. & Babin, L. A. (1999). The Influence of Product-Placement Type & Exposure Time on Product-Placement Recognition. International Journal of Advertising, 18(3), 323-337. doi.org/10.1080/02650487.1999.11104764

Bressoud, E., Lehu, J. & Russell, C. A. (2010). The Product Well Placed: The Relative Impact of Placement and Audience Characteristics on Placement Recall. Journal of Advertising Research, 50(4), 374-385. doi.org/10.2501/S0021849910091622

Cadogan, J. (2010). Comparative, Cross‐Cultural, and Cross‐National Research. International Marketing Review, 27(6), 601-605. doi.org/10.1108/02651331011088245

Campbell, M. C. & Keller, K. L. (2003). Brand Familiarity and Advertising Repetition Effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(2), 292-304. doi.org/10.1086/376800

Carr, D. J. (2005). An Investigation Into the Comparative Cognitive Impact of Conventional Television Advertising and Product Placement [Thesis, Kutztown University of Pennsylvania]. ProQuest. https://bit.ly/2Gtt3et

Chan, F. F. Y. (2012). Product Placement and Its Effectiveness: A Systematic Review and Propositions for Future Research. The Marketing Review, 12(1), 39-60. doi.org/10.1362/146934712X13286274424271

Chan, F. F. Y., Petrovici, D. y Lowe, B. (2016). Antecedents of Product Placement Effectiveness Across Cultures. International Marketing Review, 33(1), 5-24. doi.org/10.1108/IMR-07-2014-0249

Chang, S. (2003). Product Placement Deals Thrive in Music Videos. Billboard, 115(48), 18-19.

Craig‐Lees, M. (2008). Perceptions of Product Placement Practice Across Australian and US Practitioners. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 26(5), 521-538. doi.org/10.1108/02634500810894352

Englis, B. G. (1991). Music Television and Its Influences on Consumer Culture, and the Transmission of Consumption Messages. NA-Advances in Consumer Research, 18, 111-114.

Englis, B. G., Solomon, M. R. & Olofsson, A. (1993). Consumption Imagery in Music Television: A Bi-Cultural Perspective. Journal of Advertising, 22(4), 21-33. doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1993.10673416

Euromonitor International. (2019). Economies and Consumers Annual Data | Historical. Passport: Euromonitor International. https://bit.ly/35216o6

Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. London, United Kingdom: Sage.

Galpin, J. S. & Krommenhoek, R. (2013). Course Notes For Statistical Research Design and Analysis. Johannesburg, South Africa: School of Statistics and Actuarial Science, University of the Witwatersrand.

Ginosar, A. & Levi-Faur, D. (2010). Regulating Product Placement in the European Union and Canada: Explaining Regime Change and Diversity. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 12(5), 467-490. doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2010.516512

Gould, S. J., Gupta, P. B. & Grabner-Kräuter, S. (2000). Product Placements in Movies: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Austrian, French and American Consumers' Attitudes Toward This Emerging, International Promotional Medium. Journal of Advertising, 29(4), 41-58. doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2000.10673623

Gupta, P. B. & Lord, K. R. (1998). Product Placement in Movies: The Effect of Prominence and Mode on Audience Recall. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 20(1), 47-59. doi.org/10.1080/10641734.1998.10505076

Homer, P. M. (2009). Product Placements. Journal of Advertising, 38(3), 21-32. doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367380302

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W. & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies. Thousand Oaks, United States: Sage.

Hoyer, W. D. & Brown, S. T. (1990). Effects of Brand Awareness on Choice for a Common, Repeat-purchase Product. Journal of Consumer Research, 17(2), 141-148. doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/208544

Huang, I., Scale, J. & Mcintyre, R. (1976). The Von Restorff Isolation Effect in Response and Serial Order Learning. The Journal of General Psychology, 94(2), 153-165. doi.org/10.1080/00221309.1976.9711604

Hudders, L., Cauberghe, V., Panic, K., Faseur, T. & Zimmerman, E. (June 2012). Brand Placement in Music Videos: The Effect of Brand Prominence and Artist Connectedness on Brand Recall and Brand Attitude. In Anonymous (Presidencia), ICORIA 2012: The Changing Roles of Advertising. Communication presented in the 11th International Conference on Research in Advertising. Stockholm, Scandinavia.

IbisWorld (2019). Global Music Production and Distribution. IBISWorld Industry Report.

Karrh, J. A. (1995). Brand Placements in Feature Films: The Practitioners’ View. In C. S. Madden. (Ed.), Proceedings of the 1995 Conference of the American Academy of Advertising (pp. 182-188). United States: American Academy of Advertising.

Karrh, J. A. (1998). Brand Placement: A Review. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 20(2), 31-49. doi.org/10.1080/10641734.1998.10505081

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-based Brand Equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1-22. doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700101

Kotabe, M. & Helsen, K. (2009). The SAGE Handbook of International Marketing. London, United Kingdom: Sage.

Kotabe, M. & Helsen, K. (2004). Global Marketing Management. New York, United States: Wiley.

Krishen, A. S. & Sirgy, M. J. (2016). Identifying With the Brand Placed in Music Videos Makes Me Like the Brand. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 37(1), 45-58. doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2015.1119768

Law, S. & Braun, K. A. (2000). I'll Have What She's Having: Gauging the Impact of Product Placements on Viewers. Psychology & Marketing, 17(12), 1059-1075. doi.org/10.1002/1520-6793(200012)17:12<1059::AID-MAR3>3.0.CO;2-V

Lord, K. R. & Putrevu, S. (1993). Advertising and Publicity: An Information Processing Perspective. Journal of Economic Psychology, 14(1), 57-84. doi.org/10.1016/0167-4870(93)90040-R

Macdonald, E. & Sharp, B. (2003). Management Perceptions of the Importance of Brand Awareness as an Indication of Advertising Effectiveness. Marketing Bulletin, 14. https://bit.ly/31TnaiL

Mackay, T., Ewing, M., Newton, F. & Windisch, L. (2009). The Effect of Product Placement in Computer Games on Brand Attitude and Recall. International Journal of Advertising, 28(3), 423-438. doi.org/10.2501/S0265048709200680

Martínez Serna, M. C. (2004). Orientación a Mercado. Un Modelo Desde la Perspectiva de Aprendizaje Organizacional. México: Consulta S.A. y Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes.

Matthes, J. & Naderer, B. (2015). Product Placement Disclosures: Exploring the Moderating Effect of Placement Frequency on Brand Responses Via Persuasion knowledge. International Journal of Advertising, 35(2), 185-199. doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1071947

Matthes, J., Schemer, C. & Wirth, W. (2007). More Than Meets the Eye. International Journal of Advertising, 26(4), 477-503. doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2007.11073029

Mikołajczyk, A. (2015). Product Placement in Brand Promotion. Contemporary Economy Electronic Scientific Journal, 6(2), 11-19. https://bit.ly/351UkhZ

Mintel (2019). Music and Other Audio - CDs, Streaming, Downloads & Podcasts. United Kingdom: Mintel Reports.

Moran, W. T. (1990). Brand Presence and the Perceptual Frame. Journal of Advertising Research, 30(5), 9-16.

Nelson, M. R. (2002). Recall of Brand Placements in Computer/Video Games. Journal of Advertising Research, 42(2), 80-92. doi.org/10.2501/JAR-42-2-80-92

Newell, J., Salmon, C. T. & Chang, S. (2006). The Hidden History of Product Placement. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 50(4), 575-594. doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem5004_1

Okazaki, S., Mueller, B. & Taylor, C. R. (2010). Global Consumer Culture Positioning: Testing Perceptions of Soft-Sell and Hard-Sell Advertising Appeals Between US and Japanese Consumers. Journal of International Marketing, 18(2), 20-34. doi.org/10.1509/jimk.18.2.20

Omarjee, L. & Chiliya, N. (2014). The Effectiveness of Product Placement in Music Videos: A Study on the Promotion Strategies for Brands and Products to Target the Y Generation in Johannesburg. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(20), 2095-2118. doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n20p2095

Pendleton, J. (1988, November 9 th.). Hollywood Buys the Concept. Advertising Age, 59, 158.

Perlitz, M. & Seger, F. (2004). European Cultures and Management Styles. International Journal of Asian Management, 3(1), 1–26. doi.org/10.1007/s10276-004-0016-y

Plambeck, J. (2010, July 5th). Product Placement Grows in Music Videos. New York Times. https://nyti.ms/2QSwRI1

Prahalad, C. K. & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-Creation Experiences: The Next Practice in Value Creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5-14. doi.org/10.1002/dir.20015

Rodriguez-Lopez, J. & Perez-Rufi, J. P. (2017). El Videoclip Como Espot: Presencia y Evolución del Product Placement en el Vídeo Musical. Origen, Propiedades y Tipología. Pensar la Publicidad, 11, 69-82. doi.org/10.5209/PEPU.56394

Roozen, I. & Claeys, C. (2009). Are We Aware of Product Placements in Music Videos? Working Papers, 2009(38). https://bit.ly/2Z1r47c

Rossiter, J. R. & Percy, L. (1983). Visual Communication in Advertising. In R. J. Harris (Ed.), Information Processing Research in Advertising (pp. 83-125). Hillsdale, United States: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Russell, C. A. & BelcH, M. (2005). A Managerial Investigation into the Product Placement Industry. Journal of Advertising Research, 45(1), 73-92. https://bit.ly/32QZpap

Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research Methods for Business Students. New York, United States: Pearson.

Schemer, C., Matthes, J., Wirth, W. & Textor, S. (2008). Does “Passing the Courvoisier” Always Pay Off? Positive and Negative Evaluative Conditioning Effects of Brand Placements in Music Videos. Psychology & Marketing, 25(10), 923-943. doi.org/10.1002/mar.20246

Schmidt, H. (2011). From Busta Rhymes' Courvoisier to Lady Gaga's Diet Coke: Product Placement, Music Videos, and the Third-Person Effect. The Florida Communication Journal, 39(2).

Solomon, M. R. & Englis, B. G. (1994). Reality Engineering: Blurring the Boundaries Between Commercial Signification and Popular Culture. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 16(2), 1-17. doi.org/10.1080/10641734.1994.10505015

Stephen, A. T. & Coote, L. V. (2005). Brands in Action: The Role of Brand Placements in Building Consumer-Brand Identification. In K. Seiders & G. B. Voss. (Eds.), 2005 AMA Winter Educators’ Conference Marketing Theory and Applications (pp. 28-29). Chicago, United States: American Marketing Association. https://bit.ly/3lN3mp8

Stern, B. B. & Russell, C. A. (2004). Consumer Responses to Product Placement in Television Sitcoms: Genre, Sex, and Consumption. Consumption Markets & Culture, 7(4), 371-394. doi.org/10.1080/1025386042000316324

Sun, S. & Lull, J. (1986). The Adolescent Audience for Music Videos and Why They Watch. Journal of Communication, 36(1), 115-125. doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1986.tb03043.x

The Economist (2005, October 27th). Product Placement: Lights, Camera, Brands. The Economist. https://econ.st/3gWdgB6

Tiwsakul, R., Hackley, C. & Szmigin, I. (2005). Explicit, Non-integrated Product Placement in British Television Programmes. International Journal of Advertising, 24(1), 95-111. doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2005.11072906

Tiwsakul, R. A. & Hackley, C. (2009). The Meanings of ‘Kod-Sa-Na-Faeng’-Young Adults’ Experiences of Television Product Placement in the UK and Thailand. NA-Advances in Consumer Research, 36, 584-586. https://bit.ly/31V69EI

Tsai, M., Wen-Ko, L. & Liu, M. (2007). The Effects of Subliminal Advertising on Consumer Attitudes and Buying Intentions. International Journal of Management, 24(1), 3-14. https://bit.ly/3hZDYdy

Van Reijmersdal, E. A., Neijens, P. C. & Smit, E. G. (2007). Effects of Television Brand Placement on Brand Image. Psychology & Marketing, 24(5), 403-420. doi.org/10.1002/mar.20166

Wallace, W. P. (1965). Review of the Historical, Empirical, and Theoretical Status of the Von Restorff Phenomenon. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 410-424. doi.org/10.1037/h0022001

Walsh, I., Holton, J. A., Bailyn, L., Fernandez, W., Levina, N. & Glaser, B. (2015). What Grounded Theory is… a Critically Reflective Conversation Among Scholars. Organizational Research Methods, 18(4), 581-599. doi.org/10.1177/1094428114565028

White, R. A. (1983). Mass Communication and Culture: Transition to a New Paradigm. Journal of Communication, 33(3), 279–301. doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1983.tb02429.x

Williams, K., Petrosky, A., Hernandez, E. & Page JR, R. (2011). Product Placement Effectiveness: Revisited and Renewed. Journal of Management and Marketing Research, 7. https://bit.ly/3hVz55g